London Tuesday 12th June 2007 Toynbee Hall 28 Commercial Street, London E1 6LS

Chair Cllr Patrick Vernon LB Hackney

Jazz Boghal, Regional Public Health Group London:

Introduction – Ethnic health & health inequalities

Background to partnerships for health

New partnership arrangements for public services

Impact on ethnic health

Regional & local potential for ethnic health in London

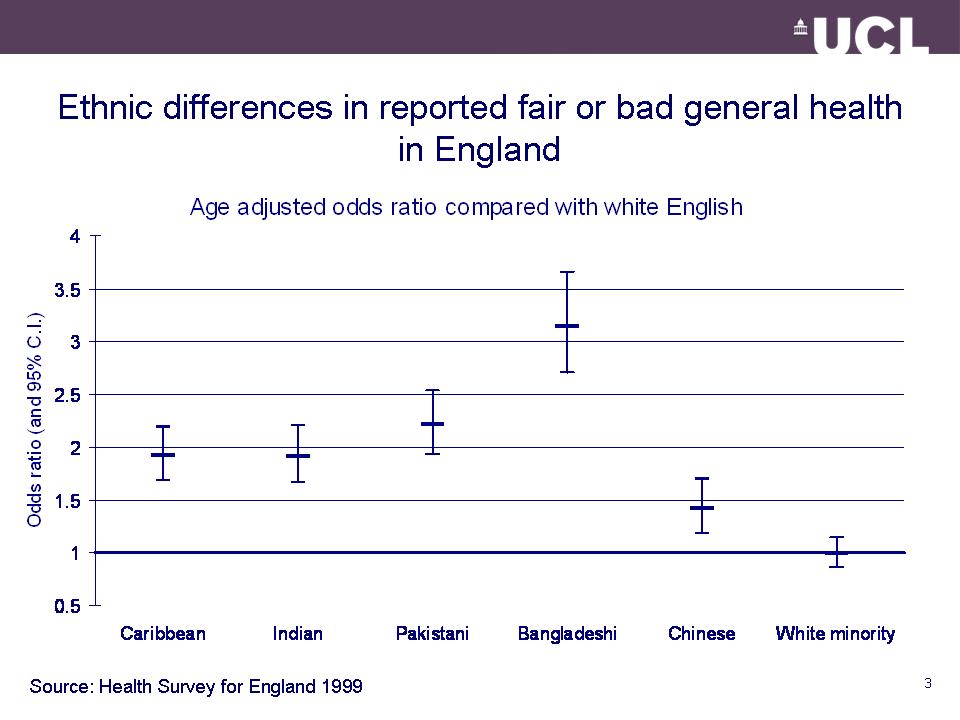

Ethnic health & health inequalities

Disproportionate rate of mortality & morbidity amongst certain ethnic groups

Non-homogenious communities

Multi-layered inequalities – multiple deprivation + discrimination

“Institutional racism knew no bounds… still doesn’t”

Public services & level of priority

Influencing action – Legislative imperative ‘v’ needs based action

Background – national perspective

Concern about health inequalities…

- The Black Report 1980

- The Acheson Inquiry 1998

- The Wanless Reports; 2002, 2003, 2004

- Comprehensive Spending Reviews; 2000, 2004, 2007

- Action on health inequalities…

- Neighbourhood Renewal Unit

- Tackling Health Inequalities: A programme for action

- Spearhead group of authorities

- Local Area Agreements

National evidence and research well supported, but poor implementation

Background – local perspective

- Local community action and involvement

- Role of the 3rd sector & BME CVS

- Engaging in local partnerships

- Increasing political engagement

- Priority status of ethnic health is variable and underestimated

- Poor evidence to support action at a local level

New requirements for partnerships

“Strong & Prosperous Communities”

New Local Area Agreements

Duty to work in partnership- Shift from national to local emphasis

“Local Government & Health Bill” Duty of partnership between Local Authorities & PCTs Focus on local health & well-being needs

Local accountability ‘v’ delivery within a national context

- “Choosing Health” – “Health Challenge England”

- “Our Health, Our Care, Our Say” – “Health & Well-being Commissioning Framework”

Opportunities for health improvement – LONDON

- Focusing national delivery targets on BME communities

- Focusing on deprived wards/priority boroughs = focus on BME communities

- London’s public service priorities; TB, HIV & sexual health, mental health, school exclusions, community cohesion, 2012.

- GLA & Mayor of London – Mayor’s Commissions, Mayoral Strategies & Assembly’s Scrutiny role.

- Changing culture and interest from public services.

Opportunities for health improvement – LOCAL

- New local arrangements and statutory duties for partnership

- Re-prioritisation of local needs against national priorities

- Delivery focus on those most in need

- Increase in BME civic involvement

- Increased local accountability

- New expectations for the 3rd sector

Partnerships at work…

Health inequalities gap is closing in London… but only just

Every LAA in London includes outcomes for BME communities (most for health)

All public service priorities in London have potential for a positive impact on BME health

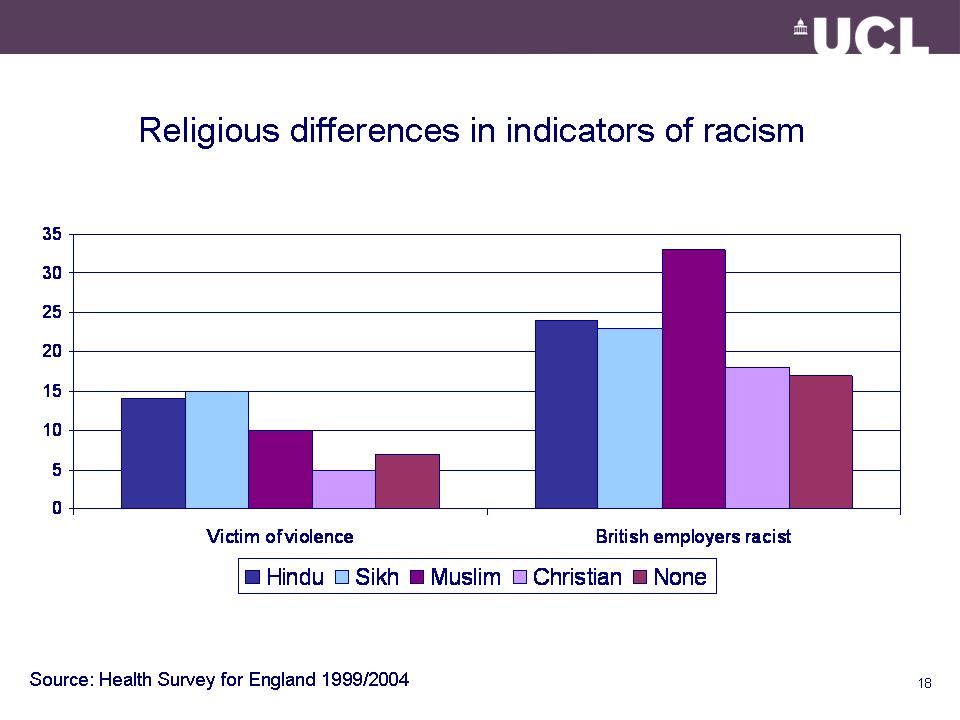

Dr Saffron Karlsen Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL:Relationships between ethnicity, racism, class and health

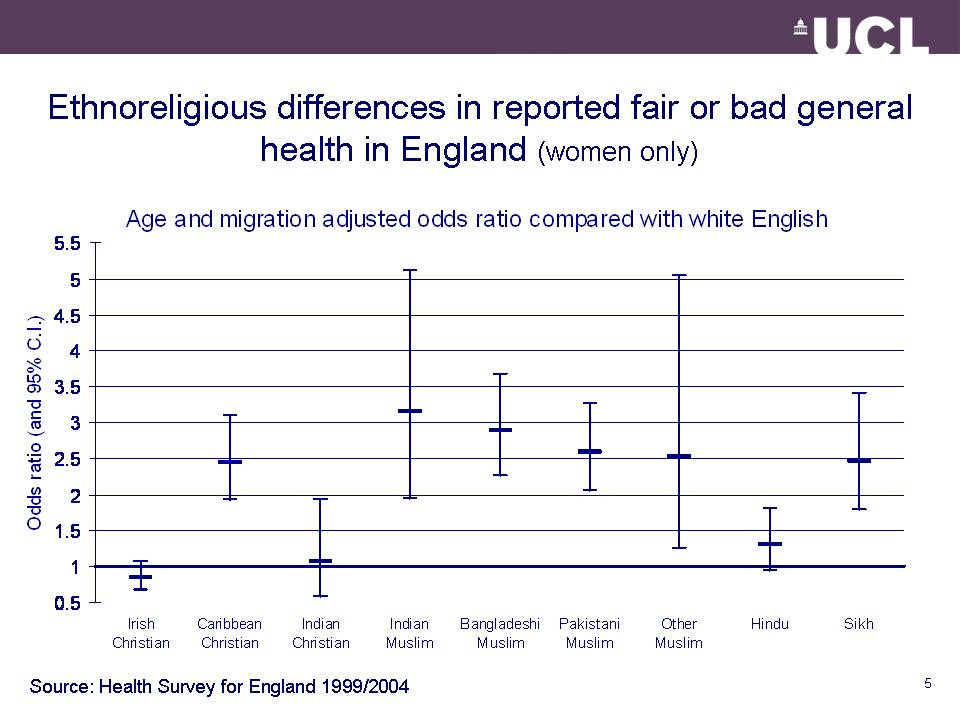

Ethnic differences in health

Common explanations

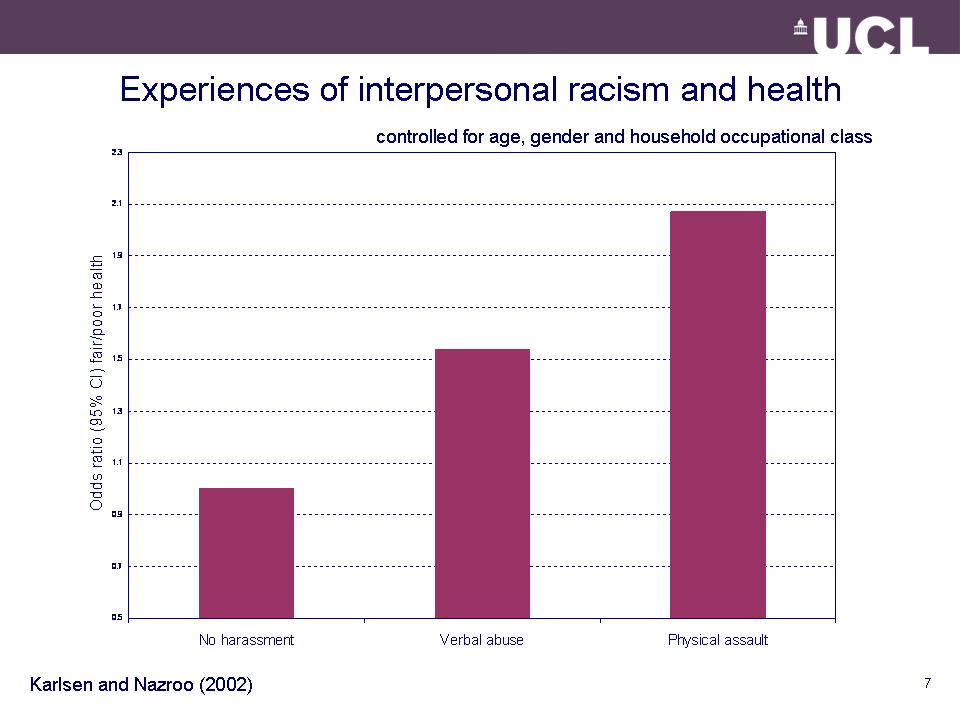

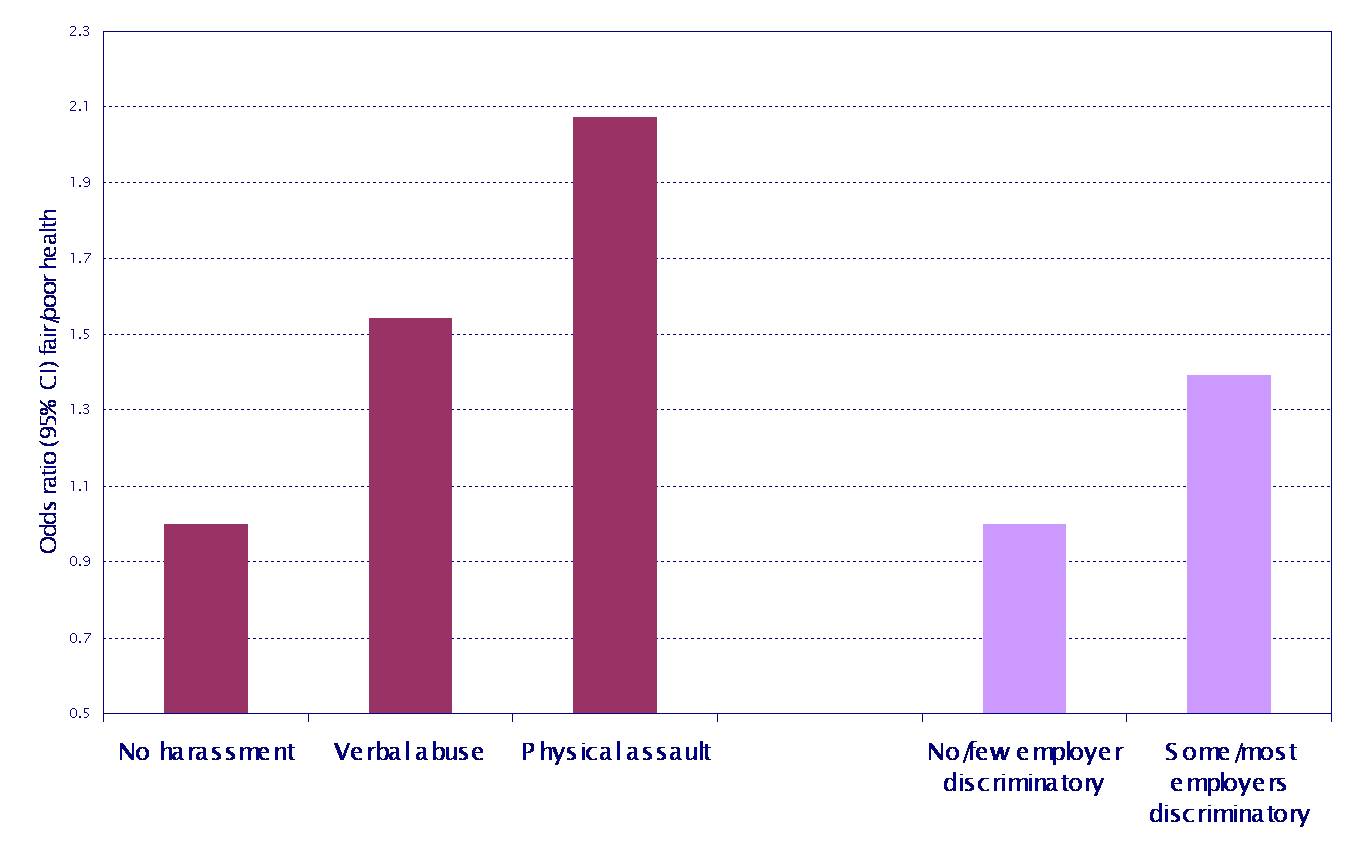

Effects of racist victimisation on –

- health

- social class

- ethnic and community awareness

Explaining the relationship between ethnicity and health:

- Genes

- Attitudes and behaviours

- Environment

- Racism

- Social class

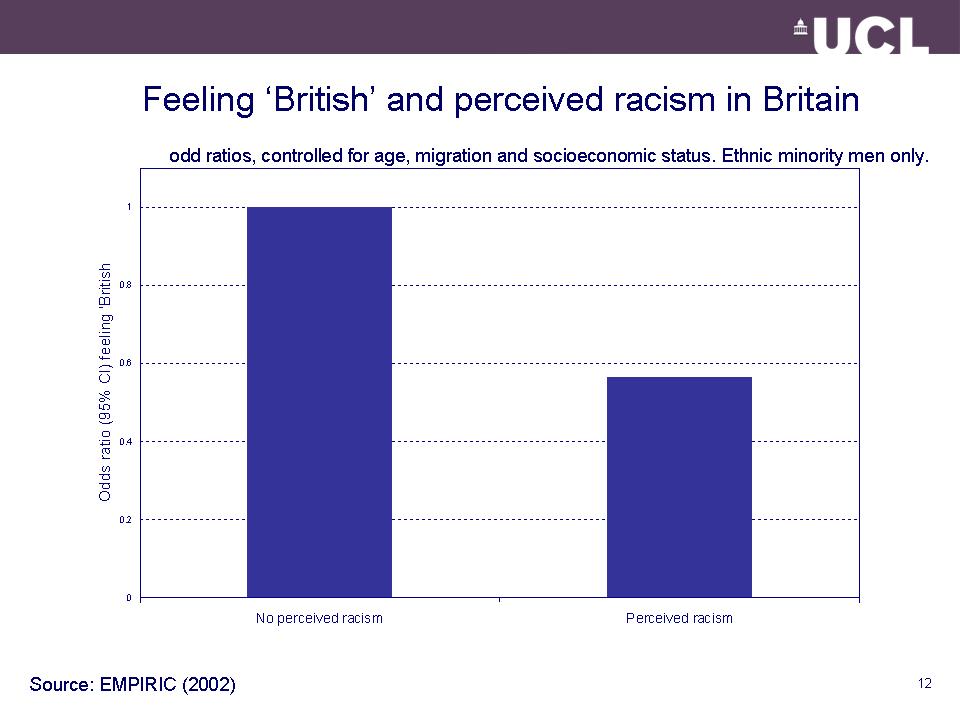

- Identity

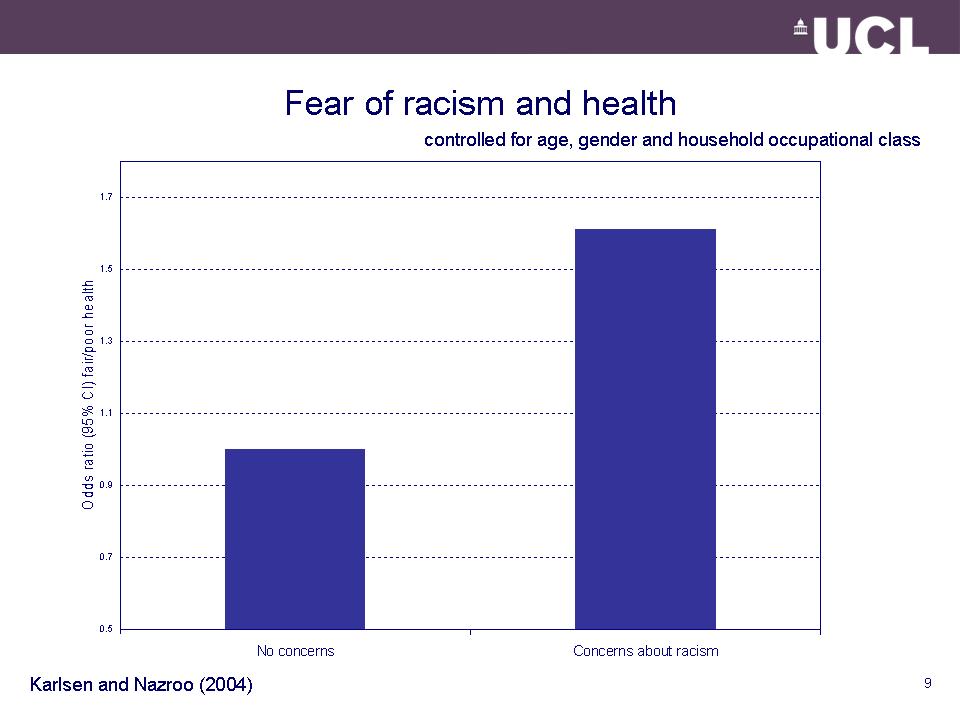

The impact of racist victimisation on health:

- Direct health effect

- Social exclusion

- Social disadvantage

- Environmental disadvantage

- Self perception

- Community development

Not being ‘accepted’ as ‘British’:

[People] judge you the minute you walk into a room, they have certain expectations of you and how they… expect you to behave

I’m English, that is my number one culture…I may not be accepted but my culture is English

I always Pakistani…you can’t change…if I go out people won’t say I’m English, they will say, “oh you’re Asian… you’re coloured”

Common stigma as source of group identity:

How long have Black people been in this country and you’re still going on with this crap [distrust]?…but this is what people put on us [Black people], this stigma

It happens all the time as a Black person…I know to expect it really

Every person with colour has to learn…to restrain [from reacting to harassment]

Racism as part of everyday life

it’s very, you know, downhearting because…you’re not appreciated and that is very sickening…[but] you can’t just shut [the shop] and say, well, I’m going home because I’m getting abuse…you’ve got a family to feed

…it was just accepted as it happened. You got used to being abused

Being ‘let down by the system’

Society tends to close their eye to some of the racism that goes on

Black people are not going out there [and voting] because no matter what they do nobody listens

It doesn’t matter if the system isn’t helping you – we help ourselves… as a group: if one is stuck we’ll ask each other and then we’ll find out where to go [how to help]

Conor McGinn, Health Development Officer, Federation of Irish Societies:

The Irish in Britain

The Federation of Irish Societies (FIS) is the national organisation for the Irish in Britain. It promotes the interests of Irish people through community care, welfare advice, health promotion, education, culture and arts, youth and sports activities and information provision. FIS has over 100 affiliate organisations across the country working for the Irish community

In the 2001 Census, approximately 691,000 people in the UK identified themselves within the White Irish category, thus comprising 1% of the population (Census 2001). 624,115 persons or 1.3% of the population in England identified as ethnically Irish. Of these, 66% were born in the Republic of Ireland, 9% were born in Northern Ireland and 23% were born in England, this last figure reflecting numbers of those whose parents/grandparents were born in Ireland

The age profile of the Irish community is an older one with significantly higher numbers in the post pension and pre-pension age group

Fewer married couple-households than White British households

38% of Irish people live in one person households

The Health of the Irish in Britain

- Significantly high rates of all-causes mortality among first, second and third generation Irish. The health of the Irish in England is worse than the Irish in Ireland, as well as worse than White English people

- There has been no improvement in Irish mortality rates in the last couple of decades. Exceptionally high deaths mortality rates for suicides, cancers, accidents and respiratory disease, raised rates for coronary heart disease and stroke

- Significant incidence and mortality for many cancers affecting both first and second generation Irish, particularly lung cancer

- Exceptionally high prevalence of permanent sickness/disability, limiting long-term illness, perception of health being ‘not good’ and highest percentage of special needs households in London.

- High mental health admissions, attempted suicides, average use of community mental health services and high rates of GP consulting for psychological problems

- Highest rates of heavy smoking and disproportionate use of drug and alcohol treatment services, given wider population figures

- Irish Travellers’ health status is comparatively even poorer, although less comprehensive data on Travellers were available. Morbidity data show excessively poor health status both physically and psychologically

Context of the Health of the Irish in Britain

Research conducted for the Department of Health (DH) notes that the BME agenda in Britain has generally excluded Irish people. The Irish are an ‘invisible’ minority aggregated into the overall ‘White’ category despite provisions in the Race Relations Act (2000) and DH/NHS guidelines. Despite overwhelming evidence of significant Irish health disadvantage there has been little attempt of the part of policymakers and practitioners to consider ways of reducing these inequalities.

Taking Steps to Address Irish Health Inequalities

- DH should include an Irish category in all monitoring of health and social care commissioned services and partner agencies

- PCT and social care staff should trained in cultural sensitivity and have knowledge of the health vulnerabilities of the local Irish population

- PCTs and local authorities should support Irish community health capacity building

- The Irish community should be represented on key local strategic planning and development bodies

- PCTs should facilitate more effective engagement of the local Irish population in local health matters

- Statutory agencies should acknowledge the Irish population in key documents affecting race, ethnicity and health

- Increased partnership working and networking between the Irish community, BME groups and statutory sector

- DH should support campaigns about Irish health and use social marketing to address the key health issues

Actions for improvement

- Recognition

- Access

- Engagement

Notes from the discussions:

1.Accountability:

Different sorts of accountability. LAAs and frameworks for delivery in a structure. Working inside established mechanisms. Awareness of what the body is obliged to do for BME issues – what can we ask them?

Transparency of process – knowledge of complaint procedures which BME organisations can use

Need to be in the loop – join umbrella bodies and use them. Accountability of BME organisations – do they represent the whole community?

Showing people how the system works. Education empowers.

Can politics and democracy deliver change?

Need for NHS to be more accountability

2. Getting your voice heard

Whole system approach – attack the key determinants of health – NHS is only a small part of this.

Use PCT and Local authority structures.

Strategic commissioning groups, councillors, media can be given local information.

You need passionate advocates who can deliver or people will give up.

Not tokenism.

Networking is an important mechanism for lobbying.

End of initiativitis – or validated outcomes

Are advocates to be paid, or must they be volunteers? Expenses should be met. Issues of stress on individual community representatives

3. BME Collaboration

Find commonality and joint projects.

Ongoing training and discussion – People centred approach

Diversity of decision makers – Boards, staff and workforce to reflect community

Local communities change rapidly

4.Evidence

Effect of individual budgets will mean that BME organisations will have to sell their services on an individual basis.

Will collecting evidence get you anywhere?

Focus groups, surveys, websites, petitions…

Educate people to know they have rights. Build up trust with communities. Building relationships – hard work.

Where does the evidence go? Needs advocate.

Sensitivity to deprivation, victim culture

Ethnic categories may not relate to local needs

Teaching communities how things work

Social change and mobility

Mentoring

Workforce issues

Access to primary care for BME groups