Control And Administration

So far we have discussed the medical services almost entirely from the points of view of the doctor and patient. The conception of a service, however, involves a method of administration and the development of a method of control so that the service may actually achieve what is hoped from it, and so that the different sections may be kept in constant touch with each other. It is essential that the form of control introduced should prevent the system becoming too bureaucratic and surrounded with hard and fast rules on the one hand, or too haphazard both in the quality of the service it provides and the methods it uses on the other.

Before considering administration and control in detail it will be as well to summarize what has been suggested for patients and for doctors. Something has yet to be said on how long it will take the system here proposed to develop and of the steps that will be necessary to achieve the ideal service that has been set out. These steps are, however, simple and of relatively short duration and the scheme suggested is one that can be achieved in the next generation and probably within the next five or ten years.

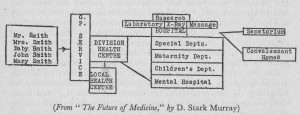

For patients we have suggested a medical service based on a system of health centres devised to serve a particular unit of population. The service is best summarized in diagram 3 which; should be contrasted with that in Chapter 2. The family is now treated as a unit and the service provided is identical for the family as a whole and for every individual in the family; it-extends therefore from the ante-natal period throughout the whole of life. For all medical services the family applies to the general practitioner service at its health centre; if the application is for advice on health matters, for a periodic health examination or for treatment for a non-urgent condition, one of the doctors attached to the health centre can be chosen and seen by appointment either at the health centre or at home. The health centre is that one of a group of three or four placed to the best advantage of the greatest number of the population it serves and working as a branch of the Division Health Centre which is attached to the local hospital. Through this health centre hospital treatment and all forms of specialist service and consultant advice are obtainable on the request of the general practitioner; every section of the medical service outside the scope of general practice is available to all patients in this way.

In this way it will be seen it has been possible to provide the type of service which is directed towards the prevention of disease, the relief of sickness, the restoration of health, and the achievement of positive health by a free provision of all necessary medical services. From the doctor’s point of view such a service would have many advantages, none of which can be achieved completely in any way except by a full-time salaried service both for general practitioners and for specialists.

In a service on the health centre model the doctor will have security both financial and professional; he will be provided with the best and latest equipment; he will take his part as a member of an efficient team whose only aim is that of providing the best possible health service; and he will be given working conditions which will be in every way superior to those of the present day. We are firmly convinced that this statement applies to every type of practice from that of the hard-working slum doctor who, in his isolation, cannot hope to give even a reasonable service to his patients and lives a life of drudgery, right up to the wealthiest and most respected of our consultants who earns a high financial reward at the expense of an application of energy output unequalled in any other profession. Professor John A. Ryle has recently suggested that the profession will decide that it is preferable to adopt a plan that imposes discipline which ensures that things are done better than before, rather than “the freedom to do things badly”. He summarizes the advantages for the doctor of a whole-time salaried service in these words—”For the loss of certain rights and privileges inherent in the old order, the advocates of a complete State service offer in the new, freedom from the injustices and restrictions due to the expense of illness and to medical self-interest where the people’s health is concerned, and from the shackles of economic uncertainty, inferior conditions of work and much unrelieved drudgery where the doctors are concerned. In brief they offer the rights and privileges—for the first time in our history—of a whole-hearted service working on behalf of the nation for the advancement of medical science, of national economy and health, and of humane projects.”

In administration the first point to be made is that a socialized medical service must be a national one. It is an essential feature that the same quality of service should be available throughout the country, and that the whole health service should be regarded as a unit within which all doctors are employed and promotion of the doctor is easily arranged. As a national service it must come under the control therefore of a Ministry of Health; but one must hasten to add a Ministry of Health on a totally different plan and scale from that which exists at present. The Ministry of Health of to-day does not control medical care throughout the country, concerns itself with many subjects which could be better dealt with by other machinery, and has never been fortunate enough to have a Minister of Health capable of conceiving the part which he could play in advancing the health of the nation and of the individual citizen. In certain problems the Ministry of Health has undoubtedly played an important and progressive part, but it bears no resemblance to the Ministry of Health, which would have under its care not only the medical service catering for the health and sickness of the individual citizen, but be engaged in shaping the policy of a country determined to provide every individual with the type of environment in which positive health would become possible.

On the exact nature of the duties of the Ministry of Health much discussion and some compromise will undoubtedly be necessary. If the profession, as one writer puts it, “can show itself competent to plan and launch a major reform, and willing at the same time to accept some sacrifice of cherished position, it should surely be within the competence of the profession and of the electorate to require major reforms and some sacrifice of tradition on the part of the Administration”. In these terms the functions of the Ministry of Health would be to initiate new and progressive schemes, ensure that uniformity of quality throughout the country which has been mentioned, to lay down minimum requirements for every branch of the service, and to encourage by all means in its power the provision of a maximum of medical care.

There is therefore no suggestion of a State medical service which would be run from Whitehall, although schemes of this type are frequently put forward. With their system of national, regional and district supervisors they approach in every respect those of the Fascist regime, and even if lacking the worst features of that type of system would inevitably be too bureaucratic to have any chance of survival in what we hope will be a truly democratic post-war world.

It has already been conceded by most students of the future of local government that one way in which the worst features, both of a bureaucratic system and of a local government based on small uneconomic units, can be avoided is by the setting up of new, elected, area authorities who will assume control of all the services in the region under their care. For the health services it appears clear that a regional form of organization is essential, and that while an area authority would be directed by the Ministry of Health as to the type of service which under existing legislation must be provided it would be for each authority most probably through a Medical Service Committee to see that the distribution and quality of the medical care in its area came up to the expected standard.

That regional authority would of course be a body elected by the local population, and we do not propose to enter very fully into the question of the ideal size of such a region. There is much discussion of this problem in local government circles and some solution must be found which will provide a unit capable of being efficiently and economically run but responsive at the same time to the wishes of the electorate, and capable— as our present County Councils seem quite incapable of doing— of stimulating sufficient interest in their activities to make the people take an active part in their election. Whether there need be a further elected body, for example, a district council, between the regional authority and the local health unit, it does not greatly affect the structure of the medical service; ultimately each health centre unit must be almost entirely autonomous, as we shall describe. What is important in setting up regional authorities is that they should not be based on existing County Council boundaries, or on a purely arbitrary section of the population, but should be based on the existing distribution of population and on natural social, economic and geographical linkages. Their variability must, however, be much less than at present when a County Council may mean that of Rutlandshire with a population of seventeen thousand, or the County of London with its teeming millions. There are, however, certain points about the medical services which suggest that there is an ideal type of region and that its population should be in the nature of two millions; and should certainly never be less than 500,000.

To the region can be applied the same criteria as to the local health unit. It must be large enough to need every conceivable type of medical service, but small enough to take into account local conditions and, when changes appear advisable, to be capable of ascertaining and responding to the wishes of the local population. Consideration must also be given to the placing of the medical teaching schools. While there is no intention of suggesting any degree of perpetuation of the present system particularly notable in the London area, whereby the holding of a part-time honorary post at a particular hospital carries with it – the privilege of teaching medical students, and while it is hoped that all hospitals will play their part in the teaching of medicine, nevertheless there must be teaching centres. Such teaching schools involve laboratories and departments which have other functions to perform in addition to those of education. While those who instruct should be chosen because of their quality as teachers it is also essential that the teaching departments should continue as research centres and as centres for carrying out special work beyond the scope of the local hospitals. The exact placing, staffing and operation of teaching schools is too involved to be discussed here.

It is necessary to note also that the same Act and Government which provides for a socialized medical service will also concern itself with the whole subject of social security. There will almost certainly be a new regional method of administering pensions, unemployment and maintenance payments, and many other subjects which come under this heading. While the payment of sick benefit must be entirely divorced from the medical services there are many points at which they touch each other, and the administrative machinery must have a somewhat similar design.

At this point we must make it quite clear that a suggestion that has come from some quarters that the health centres might be used for the payment of sickness benefit must be condemned in the strongest possible terms. The payment of money to a citizen because he or she is unable to work, whether through ordinary unemployment or because of ill-health, must be given as part of the citizen’s absolute right to maintenance. To confuse such payments with the health services would be to maintain one of the worst features of the present National Health Insurance system, which tends to make people regard disease as one way of getting back some of the contributions they have paid into N.H.I. Some other machinery must be provided for these payments which can be covered by a certificate of attendance at the health centre issued by the clerical staff there, and it might be thought that the British Post Office, accustomed as it is to handling millions of pounds of public money in other pension payments could undertake this simple duty.

So far as the medical services are concerned it will ultimately be found that administration and control will depend to a very large extent on the machinery for the appointment and promotion of the medical personnel. A suitable administrative system should be one which makes for the continued development of the professional efficiency of the staff. Professor H. B. Himsworth, in an article on this subject, suggests that “a system which provided for junior and senior posts in the proper proportion with interchange of personnel, which offered a career or promotion by professional merit, which allowed due scope to individual initiative, which by allocation of proper responsibility identified the professional pride of the medical staff with the success of the hospital, could not fail to develop that atmosphere of enquiry and enthusiasm which is the very essence of post-graduate education”. It may be added that personnel so selected would be quite capable of seeing that their section of the medical service was as efficient as possible and that under such conditions each health centre unit would be almost entirely self-governing. There is one other point to be mentioned in this connection, namely that a socialized medical service in which the whole of the necessary advice and treatment was given as the right of every citizen would require very little more administrative machinery than the maintenance of complete and clear health records at the health centre. So long as medical care is bound up with financial problems, with income categories, with division between domiciliary and institutional arrangements, and so long as a great variety of public and private funds are concerned in the matter, an elaborate system of check and counter-check, assessment and payments will be needed. Every doctor knows, however, that when he is free to see a patient without economic barriers, all that he requires is a careful note of the condition of the patient and of his previous history. Under a socialized medical service with every citizen registered at the health centre nearest his home a perfect relationship between the patient and doctor would be possible in which, without the filling up of forms, without the asking of questions as to the patient’s financial position, the whole of the necessary medical care would become available on the responsibility of the general practitioner. We look therefore to an exceedingly simple form of administration which could safely be left in the hands of the medical personnel.

In other words, the general shape of the medical service, the allocation and position of hospitals and health centres, the number of personnel required, and so on, would be settled by the Ministry of Health and Parliament through legislation, and by the regional authority through decisions made for each region, and that subject to their control the individual units constituting the medical service would be placed in the hands of the health workers concerned. There are a number of extensions to this conception, such as the exact meaning of the term “medical personnel”, and the question of whether patients require local representation on controlling committees as distinct from their general control through Parliament which will be discussed later. For the moment we would stress that the important thing is a system which will ensure that medical treatment is entirely in the hands and under the control of the medical staff of each unit and that they should have freedom to experiment and to initiate improvements in medical care. It would be their duty to indicate in advance what new improvements the service required, what its estimated, cost would be, and it would be the duty of the regional authority if satisfied that the estimates were reasonable to make a block grant to each unit and expect the medical personnel to make the greatest possible use of that in the care of their patients. Quite naturally the system would require some years of experience before it would run smoothly, and necessarily envisages a new class of personnel within the medical service who, while being laymen, would be trained to carry out the necessary administrative and financial control on behalf of the regional authority on the one hand and of the medical staff on the other.

The term “medical personnel” has in this connection two different meanings. We must conceive a body containing the representatives of every grade of worker from the hospital porter to the surgeon meeting and discussing ways in which a better service can be provided. In the health centre unit which we have discussed the total number of personnel required for the medical services will amount to some hundreds, and an organization in which all take part would be impossible, but the controlling body must be one that is representative of every section, and to which every member of every grade of staff has easy and welcome access. It is suggested therefore that each health centre unit should be controlled by a small committee containing a majority of the medical men and women who have been entrusted with the care of the health of that community with representatives of the nurses and other workers in the service.

It is a much discussed point as to whether this committee should also contain lay representatives and the matter is unlikely to be settled without experimentation; nevertheless we suggest that this is unnecessary and that most of the problems that will require to be dealt with are technical and personal and can best be dealt with by a professional body. If one were dealing with a hospital service alone, particularly with chronic patients such as those in a sanatorium, there would be much to be said for a patients’ committee, but we are dealing with a service that caters for health as well as disease and it is important that the democratic form of control should be by the ordinary one of elected representatives of the whole of the community rather than by the sectional interest of the sick.

In this question of administrative control there are many advocates of the medical superintendent system as it exists in municipal hospitals to-day. There appears to be no question that the control of hospitals is made easier by the appointment of a medical administrator. A great part of the control of a hospital can be in the hands of lay people but there is an urgent need for the development of a separate profession of lay hospital administrators trained in the work and capable of working under the direction of medical men. There are, however, a large number of problems which can only be dealt with by a doctor but he also should have, in addition to his medical training, a special aptitude and training for the administrative post. In the “Walton Plan”—one of the first detailed suggestions for a health centre system—it was suggested that the medical superintendent should control the whole medical service of the unit, but the more generally accepted view is that the majority of present day medical superintendents have neither the training nor personality for such a position and that in any case this conception tends to a bureaucratic and quite often autocratic control. The modern view is that a medical administrator is essential and must be in a position to settle day to day problems without delay, and able to link up the different sections of the medical service into one smooth running whole, but that he should be in general the servant and not the superior officer of the medical staff.

This point is of vital importance when one remembers that while in the municipal hospitals of to-day, and to a greater extent in the poor-law hospitals before 1930, the medical superintendent was not only administrator but the chief medical officer with a few less experienced medical men under him, the hospital of the future will have a staff of fifty medical men of whom some ten to fifteen will probably be better qualified than the medical administrator and in charge of departments whose work is of vital importance to the sick. The medical administrator cannot therefore be either professionally or personally superior to the rest of the staff; he should in fact be secretary to the medical committee and carry out the duties entrusted to him by that committee. It must be noted that this position can only be brought about by a change in the statutory position of the medical superintendent of a present day municipal hospital; but once again we must emphasize that this becomes very easy when it is the recognized right of every citizen, on the recommendation of a general practitioner, to immediate treatment in hospital. The present medical superintendent position is based on the old poor-law idea of providing medical treatment only for those who were poor and needy.

Provided that the conception of a Health Centre Unit serving not more than one hundred thousand people is accepted, there would appear to be no reason why a single medical committee with two medical administrators should not function for the whole unit. That medical committee would be composed of the heads of the different departments, a proportionate number of the general practitioners attached to the health centre, and one or two representatives of the nurses and other grades; it would be important also to ensure representation of the most junior sections of the staffs of both hospital and health centre. The local medical committee would be responsible to the regional authority through its Medical Service Committee, for the running of the unit.

There is hardly space here to discuss the innumerable details which this conception involves. It involves, for example, the idea that while the present day type of medical officer of health would continue to exist and would have wide powers in environmental questions he would not be in authority over the medical staffs of the individual health units; the duty of looking after the environmental services is quite sufficient without giving one man the impossible task of trying to look after the whole of the medical personnel of some twenty or more hospitals and health centres. One of the great weaknesses of the present day municipal hospitals is the idea of a chief medical officer through whom all correspondence, all new ideas and all instructions must take place; under these circumstances the medical officer of health becomes a bottle-neck which delays the employment of ideas both upward and downward and, however progressive in his own mind, a brake on the progressive ideas of others. Another conception of the past to which this medical committee would give the death blow is that a representation to an elected authority must be done by and through the senior officer; at the moment a member of a hospital staff under a local authority can only put a point of view to that authority through his medical superintendent via the medical officer of health; what this has meant in hospitals with an inefficient superintendent can be imagined. It means also that when the regional authority wishes advice on any matter it will not be tied to hearing that advice from the chief medical officer but will be able to call on any or all of the specialists that it has appointed to different departments. To take a concrete example; if a local authority, or more probably a joint education and health sub-committee of a regional authority, wishes to discuss a point on the relationship between school environment and school health it will be able to call directly for the advice of the paediatrician in charge of the children’s department of the different hospitals; to many local government representatives this appears a revolutionary idea, but it is an example of the way in which the medical profession in sacrificing some of its own traditions can enforce the abolition of local government traditions which have been far from beneficial in the past.

In speaking of the Health Unit medical committee we are not overlooking the necessity for separate committees which can through their representatives make strong recommendations to that committee on particular points; for example, the nursing profession would undoubtedly have the right to appoint a committee which would have absolute freedom to discuss and make representations on matters affecting nurses, and so on with the other grades. In the medical field there is also room for a very important development which would have tremendous repercussions on the quality of the medical service; this is the setting up of regular meetings of the staffs of the different departments to discuss with frankness and sincerity the results that were obtained in their own departments. We have in mind for example what is already a habit in many hospitals, some of which are world famous, of regular weekly meetings of the whole of the staff of one department to go over the case notes of patients who have left the hospital or died during the period under review; the effect of such meetings on raising the professional standard is certified by all who have worked in a hospital where such a system is in operation. In addition the co-ordination of the whole of the medical personnel of a neighbourhood into one unit would give a new meaning to the types of medical and scientific meetings which are at present held by the British Medical Association and other medical bodies. Medical men are very fond of meeting to discuss cases, and when these become a feature of the ordinary life of the team that constitutes the staff of a health centre and hospital they will have a greater value than ever.

We should expand also what has been said about the granting of bloc grants to a hospital; almost the whole of the money which is spent on a hospital is for items which do not vary very much and over which there is no need for close medical control, such items as the cost of heating the hospital and of the general maintenance of the patients can be fairly well standardized for the whole country; the salaries of the medical personnel would be a matter for agreement between the different grades and the regional authority, and while one hopes that the profession will make suitable agreements on this point in the spirit of an equal partner with the employing authority the total amount spent on each hospital and health centre will not vary very much. There remains an item of some ten or fifteen per cent of the total hospital budget which pays for the actual medicine given to patients, and for medical developments in the way of new apparatus, etc. It is this proportion of the hospital budget which we suggest should be the subject of a grant to the medical staff committee; the knowledge that they could meet and discuss on purely medical terms the way in which this money could best be spent for their patients would be an enormous incentive to the medical staff; indeed.it is now recognized that it is this incentive, to plan the best hospitals and to give the best and fullest possible service to the community which will stimulate the medical profession in a way that the ordinary incentive of competition so glibly spoken of by supporters of the old regime could never do; it would enable the medical staffs themselves to make this a living and vital service in which it is impossible to foresee the limits of medical progress.

The power thus placed in the hands of medical men would not be given lightly and a satisfactory machinery must therefore be provided to ensure that those appointed to the senior posts are those best suited for the positions. When the whole medical profession is in the one service this question will be partly solved at the outset of the medical education of future doctors: considerable changes will be required in the medical curriculum, changes designed to cut down the acquisitions of unnecessary and detailed knowledge such as that at present imparted in anatomy, and an increase in the time spent in practical training. This will, of course, be very much easier when every region has its medical school and every hospital and health centre is a part of the teaching system. It will then be recognized as an essential part of the training that a doctor, before qualification, shall have some experience of hospital and health centre work, and that immediately on qualification a further time on a salaried basis must be spent in apprenticeship, preferably at the health centres but also as junior officers in hospital wards. We can therefore visualize a training in which the abilities of each individual will not only be given the greatest encouragement to full fruition but in which it will be possible to assess the potential value of each new doctor with greater accuracy. When the time comes for a man or woman to begin their life’s work as a full-time officer in the section of the service for which they have a preference they should be appointed as far as is possible, to the region of their choice. The committee which makes these appointments, which arranges promotions, which decides on the movement of personnel from one place to another and from one section of the profession to another (e.g. from general practitioner to specialist) should be a committee containing some representatives of the regional authority but a majority of the senior medical officers of the region including university teachers.

It will be recollected that it is suggested that one of the conditions of employment in a socialized service will be compulsory post-graduate study; the exact nature of this post-graduate study still requires discussion, for it must be designed not only to revise a man’s knowledge of his own branch of medicine but to give him as wide a possible view of medicine as a whole. In the latter connection it is to be hoped that one feature of a socialized medical service in this country would be the interchange of medical personnel with the Colonies and with all other countries; the value for example of an interchange of a considerable number of medical men between this country and Russia is likely to be very great in the years immediately following the war. It is unlikely also that for many years to come the Colonies and Dominions will have anything like enough medical men for their own needs, and valuable experience in medicine and international co-operation generally can be gained by a system of world-wide interchange of medical personnel.

The conception of administrative control thus described is one which it is claimed would ensure nation-wide uniformity, a higher professional standard, responsiveness to democratically expressed wishes, and at the same time would meet the desire of all medical men to have no lay administrative or bureaucratic interference between themselves and their patients. It would, however, go much further for it would avoid the danger of interference between a doctor and his patient even by another medical man in the form of an autocratic superintendent; it would not, however, allow any medical man, however senior and however respected among his colleagues, to carry out his work without an organization to control the quality of that work and ensure the maintenance of the standards laid down. The medical staff committee would not only have under review the ways in which a better service could be provided but would be in a position to assess and to take whatever steps were necessary to ensure the quality of the service given by every member of the staff of the health centre unit.

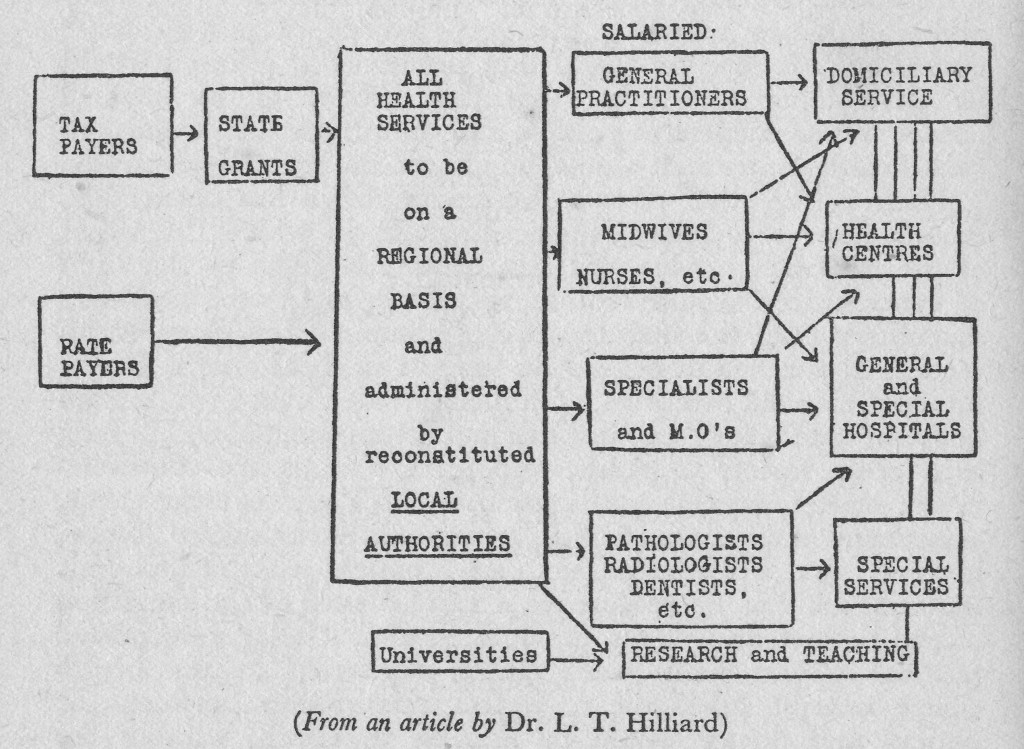

From the point of view of local government and financial control the system could not be simpler, as diagram 4 shows; when this is compared with the diagram given in Chapter 2 the advantages of a co-ordinated system are at once apparent; the greatest stress must, however, be placed on the simplicity of the machinery that is required for such a service. In place of all the elaborate machinery for collecting insurance and contributory scheme money, hospital assessments and fees for patients, and grants from State and local authorities to the hospital and other funds, we have the simple method of obtaining the total amount required for the service from ordinary revenue. In place of all the many thousands of individual practitioners, hospitals, and all the great variety of agencies that cover special sections of the community, we have one service for the sick on the simplest possible basis of full-time salaries which involve no book-keeping of any kind whatsoever. In place of the few attempts to preserve the health of sections of the community, such as infants and school children, we have a unified health service capable of preventing disease at every stage and of enabling every citizen to understand and to achieve optimum health throughout the greater part of life. In place of innumerable hospitals and unrelated general practitioners, specialists and other facilities, we have one service in which the staffs have been given the duty and the privilege of providing the very best in every branch of medical service in the most economic fashion. In the last four years the profession itself has become convinced of the advantages of such a service and the public is certainly ready to accept it. There remains for our final chapter, therefore, the need only for a brief discussion of how the service can be attained and of how the public can take from it the greatest possible advantage.