The NHS Reform Bill (now at Version 5) has caused massive disruption and great risks to the NHS and has no support. It is argued that the only reason for continuing is that stopping would be impossible as the new structures are necessary. This is nonsense.

This is a general outline of how some stability could be brought into the NHS to allow reform to continue if the Bill is stopped or delayed. Whilst considerable damage has already been done by pre legislative implementation of the widely opposed Bill organisational stability could be achieved, to be accompanied by a more inclusive planned approach to continuing reform.

It is aimed at reducing the huge risks posed by the current programme, reducing the cost of reorganisation and redundancy.

Agenda for Reform

The background to reform, expressed as sound bites, is generally agreed and has been for many years. It is the way that change is brought about that is at issue. Previous major organisational reorganisations like those in the Bill have not succeeded and tend to put genuine reforms back 2 to 3 years.

Issues around changing both the clinical and the management culture, better systems and the wider exploitation of existing good practices are far more important that organisational structures.

Key Reform Themes

These are also generally agreed. The drivers for change – demography, patient expectations, technology, medical advances are well established. Care is expected to move closer to home with reducing demand for acute capacity and increasingly some services will become more specialised with the more complex cases only treated in regional or sub regional centres (stroke care being an example). There are major issues around the closure of acute capacity, the requirement for investment in community care, the changes in the workforce and the potential for increasing the strain on social care as the transition progresses. Increasingly there will have to be integration around the needs of the patient requiring the removal of organisational barriers to this.

The impetus for these changes has to come from an alliance between the clinical leaders, local opinion formers, patients and public. Whilst there has to be some form of leadership for planned changes on the kind of scale where major services are changed, this leadership should not become the kind of dictatorial top down imposition of pre-ordained positions that characterises much of NHS reform. We need planning for change but not a huge bureaucracy to support it.

Bill Changes

The 300 plus clauses and 20 odd Schedules of the Bill (still under amendment) cover a very wide range of topics and the key ones are listed. The core of the Bill is Part 3, which deals with Competition and Economic Regulation – which is the most contentious part. The Bill is about structures, duties and powers of the many new bodies it sets up. It contains many provisions for further regulations to be made – which will provide more details.

Introducing clinically led commissioning with hard budgets DOES NOT require the Bill.

Changing the culture to limit ministerial and departmental interference and moving away from the culture of top down management DOES NOT require the Bill.

The Alternative – Key Principles

The reforms that are needed can be progressed more easily without the upheaval being introduced by the Bill. The alternative set out could be used if the Bill was stopped. It is also relevant in the case that the contentious parts of the Bill were dropped whilst the remainder which has general agreement could be the subject of a much shorter Bill that could be rapidly passed. The principles which underpin the approach are:-

- Clinically led commissioning

- Reconfiguration of care from acute to primary/community and prevention

- But investment required and potential strains on social care

- Reconfiguration through specialisation as for trauma, stroke etc

- Reducing unacceptable variation (in costs and outcomes)

- Removing barriers to the integration of care services

- Reducing inequality of outcomes

- Increasing social – health care integration and integration around patient needs

- Urgent attention to collapsing social care

Stabilisation Plan

The NHS is already embarked on a cost reduction programme on a scale never experienced before – known as the Nicolson Challenge. The stabilisation plan is based on maximising the prospects for the achievement of this programme whilst continuing with incremental changes to bring those reforms which have widespread support. The plan uses existing structures and legal framework and continues the provision of services within a managed system – rather than moving to a market system. This leaves a key role for the planning of services, involving patients and the public.

There is a need for mechanisms to facilitate reconfiguration of services especially to migrate some care from acute to primary care; these can be delivered more easily through a clinically led but planned approach than by waiting for market failure.

The plan accepts the trend for most providers of services to the NHS to be by NHS Foundation Trusts and the current efforts to allow NHS Trusts to achieve foundation status should continue through the programmes being progressed within existing structures by the Provider Development Authority.

The 4 Strategic Health Authority (SHA) and 50 Primary Care Trusts (PCT) clusters are existing legal entities responsible for commissioning services and they can exercise the necessary powers and deliver functions. They become CSHAs and CPCTs. In general CPCT are coterminous with local authority boundaries and they have responsibility for comprehensive universal health care for a defined population.

The Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) defined by the Bill but already existing in shadow form are integrated into the structures as sub committees of the CPCTs to avoid any legislative changes. The key duties, responsibilities, freedoms and scope of CCGs can remain although a comprehensive review of progress and a much greater engagement with the currently disengaged GPs would be essential.

Building a strong sense of local ownership of bodies such as CPCTs and CCG, perhaps moving along the lines of genuine stakeholder engagement, can go some way to mitigating the long established culture of top down imposition being rapidly developed under the new Clinical Commissioning Board and its many outposts. Replacing one set of bureaucracy with another will lead to disengagement of clinicians.

The longer term aim is to allow convergence of CPCT, CCGs and Wellbeing boards to provide commissioning authorities which are coterminous with local authorities but where the local health components of commissioning are still strongly influenced by clinicians.

Role of the Secretary of State (SoS)

The original bill made huge changes to separate the SoS from the NHS; this is likely to be changed. In the alternative plan the SoS retains the current role – being politically and legally responsible for the universal comprehensive NHS. The broad scope of the role which has general (but obviously not total) support is set out. Leaving the role as it is currently (as in 2006 Health Act) gives the powers to progress reforms without legislation.

Foundations

These are the building blocks of the system which are currently determined through the SoS. The development of further outcomes frameworks can be developed within current structures. Incremental adjustments to tariff, with more imagination over currencies, can be developed over time ensuring consultation with the system, not left to an economic regulator.

Competition

The role for competition is the most contentious part of the Bill. There is general agreement that there is a role for some forms of competition, for some services, but within a managed framework. There is little support or evidence to support the aim of the Bill which is to use competition and markets as the driver for reform.

The rules around competition within the NHS are set out in the Principles and Rules for Cooperation and Competition (PRCC) and are binding on all NHS organisations. Complaints about breaches of the Rules are dealt with by the Cooperation and Competition Panel/ (CCP). The scope and scale of competition is controlled by the SoS through the Mandate to the system – currently through the Operating Framework.

This current framework gives far greater protection from the intrusion of competition law and from the interference of the Courts in key decisions. Commissioners should have the freedom, within a defined framework, to take decisions in the best interests of patients without fear of intervention by Regulators or Courts.

Provider Development

The plan accepts the trend for most provision of services to the NHS to be by NHS Foundation Trusts and the current efforts to allow NHS Trusts to achieve foundation status should continue through the programmes being progressed within existing structures by the Provider Development Authority. Each Trust should have a TPA which is a plan to achieve FT status which has agreement from its principle commissioners and also with local communities affected.

A very small number of NHS Trusts are unlikely ever to achieve the conditions necessary for award of FT status. Some challenged Trusts may have to change significantly and be taken over or merged with a stronger organisation; we have also just seen direct financial bail outs being provided. The approach in the plan is to manage the process and to assist by looking at the barriers on a whole system approach. The current lengthy but highly inclusive process for reconfiguration needs to be streamlined with proper engagement with patients and the public reducing the political opportunism. Where reconfiguration spans more than one organisation they must be carried out through system leadership, mostly with the CSHAs helping to negotiate and facilitate as they do currently.

The proposals in the Bill to introduce a scheme for licensing of all providers of services to the NHS based on an economic regulation model are deferred at least until 2016 – by which time all NHS providers will be expected to be FTs. Further consultation and system design could be undertaken.

Monitor

The regulator of Foundation Trusts should retain its current role. Any consideration of Monitor or any other body becoming an economic regulator will have to be deferred.

Changes to weaken the oversight role of Monitor in relation to FTs should not be progressed, but the role of Governors can be strengthened by other non-legislative means.

The Private Income Cap applied to every FT can only be changed through primary legislation which would be contentious, as it was last time! The current level of the cap is an issue for a small number of FTs and a compromise to allow every FT to have its own level of cap set by its own governance structures might get support.

Whilst Monitor cannot be given any new powers it could be given a stronger role in an advisory capacity in respect of “market” issues. Monitor does not set policy.

Failure Regime

A large section of the Bill defines a Failure Regime – an important component of any market is for organisations to fail and exit and so be replaced by others. The alternative is to accept the reality that in some local health systems (not necessarily in a particular organisation) there are major problems; which cannot be resolved by changing the management team.

The plan retains the architecture of a managed system which allows for planned approaches to reconfigure systems to avoid failure – failure is to be avoided not encouraged as a market mechanism. A defined and structured approach to pre-failure actions for challenged organisations (or local systems) could be developed in the same way that there is already a defined process for reconfiguration of services.

Many have called for the provision of a mechanism FTs to be deauthorised (a likely outcome anyway from the Frances Enquiry). There should also be an option for an organisation to apply to be put into the failure regime so it can reconfigure itself without being driven into this by its commissioners or the regulator.

Public Health

The Bill enables the transfer of some Public Health functions, and around 40% of the budget, to Local Authorities. Other functions stay with DH or move to the NCB. The Bill treats Public Health as an afterthought and as a consequence of closing down PCTs.

Public Health is too important for a rushed and poorly thought out transition; it merits a Bill in its own right – making changes which have support from the professions.

Under the stabilisation plan the PCT functions remain where they are (but at CPCT level), and so no changes are required. This does not prevent closer collaboration and joint working with local authorities; sharing posts, budgets and preparing for the eventual shift of responsibility.

Wellbeing Boards

The Bill introduces a new set of structures within the tier one local authorities (those responsible for social care) to set up Boards which oversee certain functions which impact directly on the commissioning of care. The Bill sets out roles and membership structures, with at least one councillor and a number of defined officials per Board, plus a representative from the local health watch.

Greater involvement of local authorities is widely supported. Whilst legislation would be required to compel local authorities to set up Boards as prescribed in the Bill they do currently have enough powers to create the Boards anyway and for the Boards to carry out the functions that are envisaged. In general there is widespread support for a greater role for elected local authorities in the planning and coordination of care – especially as they are responsible for the provisions of social care.

In some parts of the country there are tier two councils (Boroughs/District’s) which have responsibilities around things like housing and environmental health which impact on health care.

The crucial role of the Boards would be to ensure that the local commissioning plans were based on an agreed strategy that was itself based on a rigorous needs analysis.

The Boards would have elected councillors but also key Officers, advisors and public and patient representatives – a model not uncommon in local government anyway. The dangers posed by “politicisation” of heath are no worse than they will be under the Bill, and having more rational local structures than those fixed in the Bill might open a better route to bringing greater democratic accountability into health.

Patient and Public Involvement

The Bill includes specific references to elements of Patient and Public Involvement, which is welcome. However key structures and functions to enable effective community and individual participation do not require legislation. What is needed more than anything else is trust. The Stabilisation Plan will make clear that effective NHS planning and provision is only possible if clinicians, citizens and patients are all signed up to the plans. CCGs and CPCTs will not be able to go it alone or they will face public backlash and possibly judicial review.

The plan will make clear that all CCGs have a duty to support:

- Shared decision-making at the level of the consultation with the patient

- Proactive community participation

- The involvement of local communities in commissioning: needs assessment, prioritising, pathway redesign, monitoring, procurement

- Appropriate governance: lay representation throughout the organisation, transparency, Nolan principles.

Commissioning Architecture

Effective commissioning is central to developing the reforms. The structure proposed under the Bill has become hugely complicated and bureaucratic whereas the stabilisation plan has a simpler initial structure with as easy route to even greater simplification.

Whilst the principle is that commissioning decisions should be made as locally as possible it remains the case that some decisions need to be on behalf of much larger populations. The “support” functions required in a commissioning system require much greater resources than the front end functions of pathway design, service specification, and priority setting.

Great care needs to be given to the level at which functions are carried out; some pathway designs may be done nationally, and be reviewed annually whilst some might be highly localised and adjusted more frequently. Some function such as provider contract management or procurement needs greater scale on some occasions and non-clinical expertise.

Back office function such as payroll, finance, and IT benefit from scale and the system simply cannot afford for every organisation to have its own support functions (as happened with PCTs). Sharing with other public bodies such as local authorities also has major benefits and incentives could be provided to encourage this.

The architecture has to be able to flex so functions can be carried out where and when it is most appropriate – implying (integration) a very close coupling of organisations and common governance. Some key functions require clinical skill, knowledge and leadership but many do not.

Commissioning organisations (CPCTs and CCGs) should all have their own Boards with non executive directors as this gives them local accountability to act as a buffer to prevent top down management. Making executives feel accountable to their Boards and not to the top down structure would help change the culture.

(Clustered) Primary Care Trusts – CPCTs

These exist and function as proper publicly accountable bodies with properly defined powers and duties. This need not change – they can delegate. They are the point at which health care commissioning is integrated. The Wellbeing Boards integrate health care with public health, social care and other public services.

They would need to commission specialist services and some of the primary and community care services which could not be delegated to CCGs due to conflicts of interest. They would also performance manage GP Practices and resolve local disputes. Where CCGs were unable, for whatever reason, to commission any services then the CPCT would undertake the role until such time as it could be passed to a CCG.

As proper pblic bodies they should have strong governance and a Board with a majority of formally appointed non-executive directors, as applies now. Having a strong local Board, with clinicians represented through both executive and non-executive appointments, will support the CCGs in achieving and using their autonomy and acting as a buffer against the top down tendencies of the system. Formal linkage to the CCGs could be established through some associate non-executive roles on the Board.

They should be required to develop a contestability regime to demonstrate services are offering quality and value for money – but they should not be under any kind of compulsion forcing them to introduce competitive mechanisms for all services.

They would be accountable to the Clustered Strategic Health Authorities (CSHAs) as now. CSHAs could become regional directorates of the NCB.

In time it is possible for CPCTs and Wellbeing Boards to converge functions and “merge” and this was the approach recommended by the cross party Health (Select) Committee. This would have to evolve at whatever speed was locally appropriate.

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)

These bodies are brought into being by the Bill but the general principle of having clinicians involved in commissioning is well established. They are going through an authorisation process which has been defined to ensure they have the necessary capacity and capability to allow then to be “authorised” to hold real budgets. There is a concerted effort to corall CCGs into being fully coterminous with local authorities; a highly desirable position but one to be reached incrementally rather than imposed.

The balance between the autonomy of the CCGs and the CPCTs is crucial as previous relationships between Practice Based Commissioners and PCTs were not always good. Having a formal board for CPCTs does allow for clinicians and others to be appointed to highly influential positions, independent of the top down structures. In the end it will be the local relationships which determine how quickly CCGs gain the control they require over their functions.

It would also be valuable to have a built in (but internal to the NHS) arbitration mechanisms should there be any issues between a CPCT and a CCG just as there was earlier if disputes occurred between NHS bodies.

The emerging governance structures for CCGs are being agreed and will be set in Regulations. The process for “authorisation” is well developed and being progressed, can be kept and does not require legislation. An early review of the experience so far and the expectations of the merging CCGs would be a valuable: this would be possible if the arbitrary implementation dates in the Bill were dropped. This might help overcome the major reservations within the professions.

It should also be clear that the pace at which CCGs take on their responsibilities will not be driven by any arbitrary cut off date and should proceed as capacity and capability allows.

The CCGs will have the role defined for them in the Bill – operating through earned autonomy – as sub committees of the CPCTs to give them proper legal from. They can hold delegated budgets (a mechanism already widely used – for example for funding various networks).

The relationship of CCGs to CPCTs will be as was set out for the relationship between CCGs and the NHS Commissioning Board. The temptation to use the top down management style would be reduced by establishing more local relationships, less likely when dealing with a national body.

As mentioned the desired end result will be local commissioning authorities coterminous with local authorities (or in some cases perhaps with two or three local authorities); to be achieved over time by agreement and incrementally without a reorganisation. Each locality should be allowed to proceed at its own pace and the clinical and professional leadership around commissioning of health and care services must be built upon not diluted.

Commissioning Support

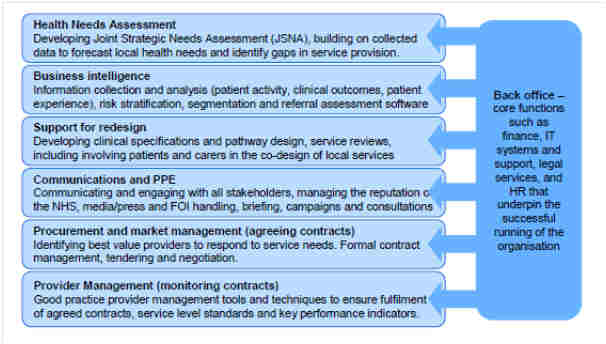

The CCGs will clearly take a strong lead role around clinical aspects of commissioning, pathway design, priority setting and service planning. There are however many other tasks associated with commissioning; procurement, contract management and data analysis as examples. There are also “back office” functions such as payroll, recruitment, finance which are best carried out at a greater scale – some potentially nationally.

The current plans under the Bill envisage Commissioning Support Units being created as standalone organisations, originally hosted within the NHS, but packaged and destined to be privatised.

The stabilisation plan attempts to avoid the marketization and the redundancy costs, disruption and risks this involves by locating the support functions within CPCTs. One possible configuration would be for a small number of larger “support” providers each of which would be “hosted” by a CPCT – a model well used for shared services within the NHS. The key is to gain the benefits of economies of scale and to retain knowledge and capability within the NHS; building on that as necessary.

These support services would be available to the CPCTs but also to the CCGs although the actual configurations would very much depend on local circumstances – for example some CCGs might be very large and so able to have “their own” services in house or even bought in from other providers; staff could then be transferred but still remain within the NHS. Flexibility is vital if economies of scale of local autonomy are both to be achieved – keeping functionality within the NHS helps this balancing act.

Examples of services which would be regarded as part of the “support” offering are shown in the diagram.

Funding Streams

Funding to providers will continue to be a mixture of payment by results and “block” payments. The funding to CCGs is still not announced but is separated into monies for administration based on population size and for commissioning based on a complex allocation formula of the traditional kind.

There will also be funding to the NCB again both for management and for the £20bn of services it is responsible for.

Proposals for the new funding regime are being finalised with the basic mechanisms for formula based allocations to the various levels of commissioning, national CPCT and CCG. The fairness of the allocations and the factors to be taken into account in allocation will always be controversial. What is important in the stabilisation plan is that allocation is a “policy” matter; it is not a devise to smooth the operation of the market.

There is no reason why these arrangements being worked out for the Bill cannot equally well be applied to the stabilisation plan structures. Aligning funding to the required outcomes, developing the tariff (which could well include LESS application of payment by results), new currencies and shared funding can all be explored as easily under the stabilisation plan.

The formal separation of the funding for management costs can be introduced.

Property Ownership

There is a huge estate owned by SHAs and PCTs and under the stabilisation plan they can remain as they are. The necessary and beneficial rationalisation of the vast NHS estate can still be achieved; and has been in some areas.

Under the Bill this estate has to be dealt with by bringing it together into a single new organisation known as PropCo. This is an obvious route to enable the property portfolio to be secutised with property sold off or leased back. Taking the infrastructure out of public ownership is also a necessary step in developing the market and public ownership of facilities is an obvious distortion to the “level playing filed”. The original Bill addressed this directly by forcing NHS bodies to allow their facilities to be used by others – this move to PropCo is driven by the same thinking.

NHS Commissioning Board

The Bill brings this new organisation (quango) into being with huge powers which its shadow form is already deploying to top down manage the transition plans! It will commission £20bn of services as well as authorising and then managing CCGs.

Giving this national body the major role in commissioning local primary care services and performance managing them is deeply flawed even if the Board has local outposts. This also disintegrates commissioning when integration is the desired policy outcome.

In the stabilisation plan there can be an NHS Board and the new ideas to have a Board which is open and transparent (webcasting its meetings and publishing its risks) is welcome. But the Board does not do commissioning. It looks a bit like previous attempts to have an NHS Operational Board looking after delivery whilst the DH looks after policy and development.

The Rest

The Bill also makes changes in a host of other areas. It is likely to be significantly amended around Training and Development and Research; changes are to be made to Arms Length Bodies; changes are foreshadowed around workforce regulation and planning. New provisions are made around information usage and the creation of the Health and Social Care Information Centre.

In general these could all be welcome changes but they have only the most tenuous connection to the core of the Bill – which is about competition, markets and regulation and about changes to commissioning architecture.

It is unclear what if any primary legislation would be required under the current legislative framework to bring about these less controversial changes; it is clear that under the structures that the Bill would put in place there would have to be the added complexity of further provisions as the powers of the SoS could not be used, as now.

Irwin Brown Feb 2012