Election Briefing Note May 2017

Summary

- The current amount of public expenditure on social care for older people in England each year is less than 0.5% of GDP. To put this in context, the UK currently spends around 2% of GDP on armaments and defence and 0.7% of GDP on foreign aid.

- The manifesto commitments of all the 3 major parties on social care mean that publicly-funded social care will remain highly rationed over the next 5 years and will only be available to those older people with the most substantial care needs.

- It is unclear whether the spending commitments made by any of the major parties will even sustain this already very low level of service coverage. As things stand local authorities will need around an extra £2.5bn year by 2020 to continue to provide a highly rationed service. The number of people receiving publicly funded social care has fallen despite the fact that the population is growing older and living longer.

- All 3 major parties are now committed to introducing a “cap” on how much an individual should pay towards their own social care costs (hitherto known as the Dilnot cap).

- In 2013 the Department of Health estimated that the Dilnot cap (if set at £72K) would cost the tax payer £2bn a year, that it would cost around £200m a year to administer (involving the additional assessment of 500,000 people) and that it would only benefit 100,000 people with significant assets.

- Most importantly, the implementation of the cap would not lead to the expansion of publicly social care to cover those with moderate care needs and so would do little to reduce the burden on the NHS or on informal carers or improve the lives of many older people.

- This briefing note shows that only by injecting a substantial amount of public funds into the care system will social care become a service which enhances the lives and independence of our older people. Capping care costs would benefit a relatively small number of people and would have little impact on either the quality or the availability of care.

Introduction

The Conservative Party’s manifesto proposals have put the funding of social care at the heart of the election debate. However, the narrow – and sometimes ill informed – commentary by the media has allowed politicians from all the major parties to avoid answering serious questions about how they will tackle the real crisis in social care and has allowed them to sidestep awkward questions about how much their proposed solutions will cost the taxpayer and who they will benefit. This briefing note sets out:

- The nature of the social care funding crisis

- The causes of the crisis

- An assessment of the solutions proposed by the 3 major parties, what they are likely to cost and who they will benefit.

This briefing note focuses on the issues relating to social care for older people, however, it should be noted that people under 65 also receive a significant amount of social care; 18 – 64 year olds receive around £6.5 billion a year. The social care funding gap set out here includes the gap between what local authorities need to provide all the social care for their local populations and not just for older people.

The social care crisis

The crisis in social care which the manifesto commitments seek to tackle is not something which will hit in 10 years time, it is happening right now.

It is a crisis where local authorities are estimating that they will need an extra £2.5bn a year in 3 years time just to continue providing the existing highly restrictive level of care to people; where gaining access to local authority funded care is impossible for all but the most dependent older people, and where both care homes and home care providers regularly go bust. The extent of the exact gap in social care funding is the subject of some debate. The Association of Directors of Social Services estimate that by 2019/2020 that around £2.6bn will need to be funded whilst the Health Foundation, Kings Fund and the Nuffield Trust estimate that the total funding needed will be £2.4bn to £2.8bn. These estimates assume that care will be restricted to only those in need of substantial care and attention and that they will fund the cost of the new national living wage. They also refer to the entire costs of adult social care and not just for those over 65. See this excellent summary here from Adam Roberts Public Finance March 2017:

It is a crisis where the workforce which provides highly intimate care services to mainly older people often receives little or no formal training and often earns less than the minimum wage. For those older people who are able to access local authority funded care at home, their time with a care worker is often rationed to just 15 minutes, whilst for those who receive care in a residential care home around 25% of the care homes in England are rated inadequate by the care home regulator. The Leonard Cheshire Disability found in 2013 that 6 out of 10 local authorities were commissioning home care in 15 minute slots.

For those whose needs are not met by the local authority and who fund their care themselves out of their own income, they too experience the same problems with poor quality of care. However, because many care homes would not survive if they relied only on the poor levels of funding from local authorities, these self-funders are often charged almost 50% a week more than local authority residents and so in effect subsidise the cost of their care.(Laing Buisson (2015), Care of Older People: UK Market Report 27th Edition.) The restrictions on the availability of state-funded care for older people places a significant burden on the so-called informal workforce, mainly female family members who have to take time out of work to care for their relatives.

In and of itself this is a crisis which affects hundreds of thousands of people and their families each day, but it also has significant consequences for the NHS. A major reason why hospital A&E departments are regularly overwhelmed and why hospital beds cannot be freed up is that local authorities do not have enough money to provide care to large numbers of older people, even those that they deem to meet their highly restrictive criteria. Thus as the social care crisis deepens so too does the crisis in the NHS.

The making of the social care crisis

The source of this crisis lies in three facts about social care provision which appear to be poorly understood by the media.

“Publicly funded social care has been rationed due to budget cuts and so is now limited to those who are most in need”

The first is that social care which is provided to older people has always been a responsibility of local authorities, not the NHS, and since the 1960s has been increasingly restricted only to those who have very significant care needs. (See Allyson Pollock, Colin Leys, David Price, David Rowland and Shamini Gnani Chapter 7 Long Term Care for Older People NHS PLC Verso 2004) This means that in order to get local authority-funded social care an individual now needs to be highly dependent, with very high care needs. In an under-reported move in 2015 the Coalition government introduced national minimum eligibility criteria to ration social care only to the most in need – in order to qualify an individual needs to have ‘substantial’ care needs – anyone deemed less needy than this must fund their own care. (The Care and Support (Eligibility Criteria) Regulations 2015)

Although the demand and the costs to local authorities in providing social care have increased – due to an aging population – central government payments to local authorities have actually reduced by 9% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2014/15. (National Statistics and NHS Digital Personal Social Services: Expenditure and Unit Costs England 2015-16 October 2016) This means that rather than being a service to assist older people to stay well and active and out of hospital, social care is a service now focused on those who have experienced a major crisis in their lives for example, following a stroke or a fall or due to the worst aspects of dementia.

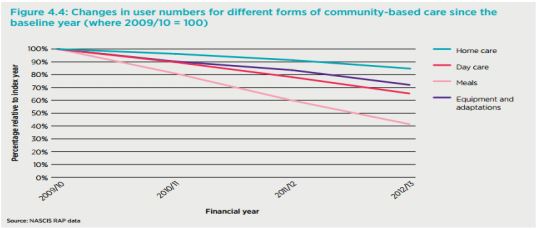

And because of the funding cuts from central government, local authorities are struggling to pay for even this highly rationed form of care. The Nuffield Trust, the Kings Fund and the Health Foundation estimate that the number of older people receiving care has shrunk by 400,000 in 5 years. ( The Kings Fund, the Nuffield Trust and the Health Foundation ‘The Autumn Statement Joint statement on health and social care’ ) This has particularly affected those types of community care such as meals on wheels or home care which can have the most impact on the independence and well being of older people (see figure below)

Finally, the share of GDP which goes into public funding of social care for older people each year in England is less than 0.5% (9 Raphael Wittenberg and Bo Hu ‘Projections of Demand for and Costs of Social Care for Older People and Younger Adults in England, 2015’ Personal Social Services Research Unit PSSRU Discussion Paper 2900 September 2015 ) . To put this in some context, the UK currently spends around 2% of GDP on defence and armaments and 0.7% on international aid. “Social care funding – unlike the NHS – has always relied on a form of “death taxes”. Because property values have increased and government has cut funding, the amount paid by older people towards their care has gone up.”

The second key fact about the social care crisis which has often been overlooked by the media is that large numbers of highly dependent older people have been denied access to state funded care because of their existing assets (usually their home) and their income (usually their pension) for many years.

Charging individuals for their care, is not a new phenomenon, nor is taking their house from them after their death to fund residential care, as this has been part of the way social care has been funded going back to the National Assistance Act 1948. Whilst charging has become more common in recent decades – again due to local authority budget cuts – it is not new. For example, a survey in 2001 found that around 70,000 older people had sold their homes in order to fund their care.(A survey of the number of people forced to sell their homes to pay for nursing or residential care, Liberal Democrats 2001)

So “death taxes” of the type being referred to in the media to pay for care are not a new phenomenon. In fact the latest survey of local authorities shows that councils have a claim against the homes of older people to pay for their care worth around £72m. ( National Statistics and NHS Digital Personal Social Services: ‘Expenditure and Unit Costs England 2015-16’ October 2016 See Appendix A )

However, charging older people for social care has become increasingly more common as more people have been assessed as having too much money or their houses have increased in prices sufficiently for them to be deemed ineligible to receive state funded care.

“Privatisation and the market in social care have been used to keep costs down to the bare minimum.”

The third fact about social care which is seemingly little understood is that in order to provide it as cheaply as possible local authorities have been under significant pressure from government to contract out the provision of care services to the private sector. As a result, over 90% of both home care (domiciliary care) and residential care (care homes) is now provided by the private sector. Through using private providers, who generally tend to pay workers less, and through getting private providers to compete with other on the basis of price, cash-strapped local authorities have sought to keep the rising costs of providing social care down to the bare minimum. (Centre for Health and the Public Interest “The future of the NHS – lessons from the market in social care in England” October 2013 )

Such an approach has driven down the quality of care (and resulted in the notorious 15-minute time slots), but it has also brought many care homes and domiciliary care companies to the point of bankruptcy. The response of the 3 main parties to the crisis – who benefits and how much is it likely to cost?

The response of the 3 main parties to the social care crisis can be broken down into two parts: providing some additional funds to just about maintain a highly restrictive service, and protecting the assets and wealth of a small number of richer older people.

“The 3 main parties are committed to keeping social care as a residual service for only those with substantial needs.”

In order to address the crisis in social care and the impact that this is having on the NHS and informal carers, a significant injection of funds is needed: to improve the quality of care available, to pay the workforce properly, but also to expand the number of people who receive state-funded care so that social care moves beyond being a service reserved for those with significant care needs to one which genuinely enhances the lives of older people and prevents them from entering into ill health and hospital prematurely. A well funded service could prevent another large-scale collapse of a care home chain, which the government predicts is highly likely to happen in the next 5 years, and prevent home care operators from cancelling their contracts with local authorities.(The Guardian ‘Care contracts cancelled at 95 UK councils in funding squeeze’ 20th March 2017 )

However, none of the 3 main party manifestos gets close to addressing (or even recognising) this need. The Labour Party does pledge to increase the amount of funding going into social care – by £8 billion over the course of the Parliament – with the aim that this will fund the increase in wages for the sector and end 15-minute care slots for those receiving home care. However, this is just about the amount necessary to fill the shortfall of £2.5bn which has arisen due to the funding cuts made under the previous two governments. As a result, Labour’s funding commitment would still only be sufficient to fund public care to older people with high care needs. Whilst it promises to do away with the 15-minute care slots and fund the national living wage for care workers, it is unclear how it could achieve this with such a small increase in funding.

The Liberal Democrats promise to spend an additional £6bn over the course of the Parliament, but this is to go on both the NHS and on social care so it is not clear whether its funding proposals would meet the existing social care shortfall. The Conservative manifesto makes no statement about additional resources to fund social care other than the additional £2bn over 3 years which has already been committed in the last budget before the election.

As a result all 3 major parties fall short in promising to fund anything above the current bare minimum of social care provision.

“The 3 main parties are all committed in some way to protecting the assets and wealth of mainly richer older people”

However, what the 3 major parties are now all committed to is insulating older people and their families from the worry of having to pay for social care. All 3 major parties are now committed to introducing the social care funding approach similar to that recommended by Andrew Dilnot in 2011. This approach is to cap an individual’s liability to pay for social care at a certain level – after which point the state will pick up the bill – as well as to increase the amount that an individual can keep before having to contribute to the cost of their care.

Whilst none of the major parties has said what level the cap should be set at there is an existing analysis undertaken by the Department of Health which explains how the scheme works, how much it will cost and who will benefit.

In 2013, when the Coalition government legislated to introduce the “Dilnot cap”, the Department of Health published an impact assessment which looked at the scheme and assumed that the cap on the total amount an individual would have to pay for their care would be around £72k. (Norman Lamb MP ‘Social Care Funding Impact Assessment’ Department of Health 08 April 2013 )

Interestingly, this impact assessment sets out that the overriding benefit of the policy is to create “peace of mind” amongst people as they entered old age as they would know that if they were to fall ill and need social care they would not be faced with “catastrophic” care costs as these would be capped at £72k level. It would also allow them to pass on £100k of their assets to their children. It does not aim to move publicly-funded social care from being a residual service to being something more comprehensive.

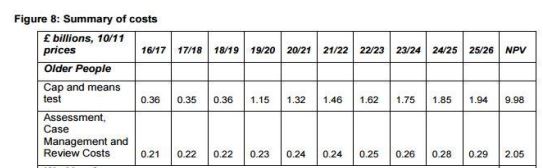

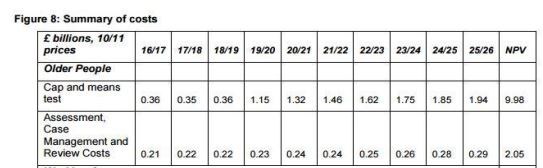

The cost of providing this “peace of mind” to people entering retirement was estimated in 2013 to be just under £10bn at 2011 prices over a 10-year period, plus an additional £2bn over the same period to administer the scheme. This works out at around £2bn a year at 2011 prices once the scheme is fully up and running. (see figure 8 taken from the DH impact assessment)

The Labour Party manifesto is the only manifesto which acknowledges that this policy will cost the taxpayer a significant amount. In fact, Labour’s national care scheme – which appears to be mainly focused on introducing the proposals similar to those recommended by Dilnot – is said to cost around £3 billion a year.(The Labour Manifesto states –“In its first years, our service will require an additional £3 billion of public funds every year, enough to place a maximum limit on lifetime personal contributions to care costs, raise the asset threshold below which people are entitled to state support, and provide free end of life care.” ) Neither the Lib Dems nor the Conservatives set out what the financial impact of this approach will be.

The 2013 Department of Health impact assessment estimates that 10 years after the scheme is introduced this scheme will benefit an additional 100,000 people who would receive care which they would otherwise have had to pay for (see figure 7 below from the DH impact assessment).

What is not mentioned by any of the major parties in their manifestos is that a significant amount of money each year – around £200m, according to the impact assessment – would need to be spent just to assess the estimated 500,000 people who would come forward seeking to access care.(This figure comes from the Department of Health consultation on the subject in 2013 ) This assessment would involve calculating their wealth and the value of their housing assets – that is £200m which would not be spent on providing care but on local authority administrators.

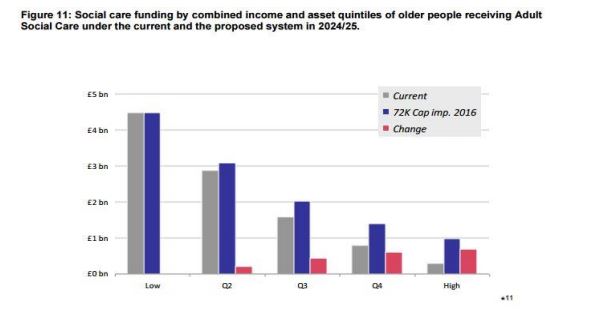

Because the purpose of the Dilnot proposals is to expand state-funded social care to those deemed too wealthy to currently access it, the 2013 impact assessment shows that the scheme would disproportionately benefit those with higher incomes and assets (the rich) compared to those with fewer assets (the poor) (see figure 11 from the DH impact assessment below) Or, as a further analysis found, by 2030 this would mean that the Dilnot Cap would be worth £52 per week (2010 prices) on average to care recipients aged 85+ in the highest quintile ( the richest group), compared with £20 per week for those in the lowest quintile (the poorest group). ( Ruth Hancock, Raphael Wittenberg, Bo Hu, Marcello Morciano and Adelina Comas-Herrera ‘Long-term care funding in England: an analysis of the costs and distributional effects of potential reforms’ Unit PSSRU Discussion Paper 2857 April 2013)

Again, there is no assumption within this approach that the changes in funding arrangements would bring in any additional resources from charges on property or income. Instead the scheme assumes that the taxpayer will fund this additional £2bn a year. So the taxpayers’ money which goes to protecting the assets of these 100k or so richer people will be money which is not available to fund or public services such as the NHS or schools.

So what would the taxpayer get for this £2bn a year? An increase in the number of people receiving social care who have lower care needs, so that the burden on the NHS can be reduced? An increase in the payment to care homes and home care operators, so that they can avoid bankruptcy and pay their staff the national living wage or invest in their training?

Unfortunately not. The costing done by the Department of Health assumes that state-funded care will still be restricted to those with very high care needs and that the current costs of providing social care – such as how much care staff are paid and how much care homes receive – will in effect remain the same for the foreseeable future. Any plans to increase payments to care providers or to expand the coverage of social care to those with lower care needs would not only send the bill for this policy soaring but would require a much more substantial increase in the overall social care budget, neither of which is contemplated within this proposal.

Conclusion

Based on the Department of Health’s analysis of the Dilnot Cap and the funding commitments set out in the manifestos, it looks as though all 3 major parties are proposing a policy which does little to address the fundamentals of the current social care crisis but which could potentially benefit around 100,000 or so people, all with significant assets depending on where the social care cap is eventually set. It is a policy which, irrespective of where the cap is set, will cost around £200m a year to run and which will do nothing to alleviate the pressures on the NHS. Whether this is worth the taxpayer paying in the region of an additional £2bn a year at a time when all major parties are proposing small increases in funding for the health service is the real question which the media should be asking.

First published by the Centre for Health and the Public Interest