A new, independent and broad-based citizens’ initiative – the People’s Plan – was launched in Greater Manchester last October and has now published its findings. This extract covers health and care – but other parts of the plan would also impact on health.

Since 2016 Greater Manchester has responsibilities for managing and integrating hitherto separate, centrally funded NHS services and local authority adult care services. Both services are in crisis: in adult care, austerity budget cuts have reduced numbers receiving home care by some 20% nationally; and in health services, the halving of the number of hospital beds over the past thirty years has created a fragile system that suffers with demand peaks or delayed discharges. The National Audit Office has questioned whether integration of health and care will save money or reduce hospital admissions; and this finding is ominous when Greater Manchester has a predicted £2 billion shortfall in health and care expenditure within five years. Against this background, it is unclear how Greater Manchester will find the policy levers, financial resources and political will to tackle prevention of ill health and low life expectancy in deprived localities.

Challenge 1:How to lever in more financial resources for health and care services, where social ownership and operation of free services should be defended

Event participants recognised that “services cannot be run without proper funding” and the first priority of survey respondents is levering in more public funding. In health, as in housing, what citizens want is public provision that depends on reversing austerity cuts. By implication, the Greater Manchester mayor and other Greater Manchester politicians need to change central priorities as much as manage local services; as a Bury event participant put it: “make it the Mayor’s job to fight for more money for local services”.

The other clear theme is that public funding should support socially owned and operated services. While voluntary and other third-sector providers are often complimented, references to private providers in health and care are mostly negative: “Resist the influence of the private sector, because it takes money out of the system”; other respondents had concerns for poor pay and conditions in outsourced adult care.

Pointers on what to do:

- Lever in more public funding.

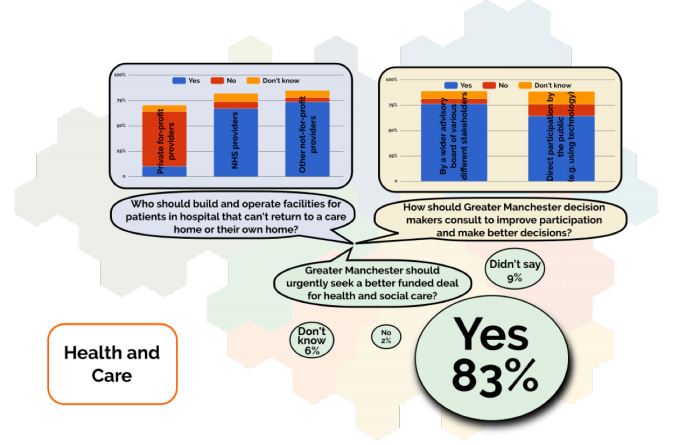

83% of all survey respondents agreed that ‘Greater Manchester should urgently seek a better funded deal for health and social care’ – with just 2% opposed. Here again, as in other policy areas, like housing, what respondents want the Greater Manchester mayor and other Greater Manchester politicians to do is not just manage the system within existing funding limits but claim more resources. For example, investment in training for ongoing supply of nurses in Greater Manchester services is an area where consequences of cuts to bursaries are a serious concern.

- Use public funds to support not-for-profit and publicly owned and operated services.

Survey respondents and event participants were against further outsourcing or privatisation. Health and care services need new ‘step down’ facilities for discharged hospital patients who cannot go back to their own homes and do not have a care home bed; but 67% of all survey respondents believed such facilities should be built and operated by NHS providers and 74% also supported provision by other not-for-profit providers, with only 10% supporting private for-profit providers.

Challenge 2: Build a new kind of NHS as a civic institution which offers a wide range of stakeholders more participation in decision-making as well as providing more user-friendly services

Citizen attachment to the NHS is not all sentimental and uncritical. Ministers and managers have sought to restructure health and care services so that they meet user demands more effectively, but citizen critics go further and ask for a redefinition of the NHS as a new kind of civic institution where a wide range of local stakeholders would have a major influence over decision-making.

At a café-style event conversation about ‘Devo Manc’, participants posed a challenge to “find ways to put health and social care close to communities”. There is widespread dissatisfaction with current forms of consultation that are too often about changes already decided by service managers.

Pointers on what to do:

- Experiment with direct public participation in decision-making.

65% of all survey respondents wanted direct participation by the public for proposed changes, through means such as online polling, for example, whose results could not be easily ignored.

- Create an advisory board representing wider interests.

More traditional forms of representative democracy have even wider support. 77% of all survey respondents wanted a wider advisory board representing different stakeholders including voluntary and community organisations as well as provider groups. For example, representation for those with learning disabilities and their many challenges was strongly featured in the Health and Care themed event.

- Provide more user-friendly services on a local community basis.

This is the point where citizen priorities align with those of politicians and service managers. At a Greater Manchester Older People’s Network event and in surveys, the GP and hospital appointments systems were described as “barriers” to access, with specific criticism about the availability of “on the day” appointments; and at a Wythenshawe event the complaint was that “public transport never lines up properly with health services”

Challenge 3: How to put more resources into prevention and into the inadequately funded ‘Cinderella’ services of mental health and adult care, which have now been damaged by austerity cuts

Many of the open survey responses and comments of event participants highlighted the problem of ‘Cinderella’ services. Some event participants thought hospitals were claiming resources that should have gone to prevention, primary and community provision; all agreed with the survey respondent who wanted “greater emphasis on prevention not cure” and worried about how austerity cuts in mental health and adult care had aggravated long standing problems about service provision. The result is pervasive insecurity about service availability, crystallised by the question at one Tameside event: ”will it be there when you or your family members need it?”.

Pointers on what to do

- Stop cuts to mental health services and increase funding.

This connects with prevention because, as one survey respondent argued, with more funding for primary care, GPs should be able to prescribe more one-on-one counselling and for more than six weeks.

- Revalue the workforce in adult care.

Some open responses registered the point that care workers are paid and trained worse than health service workers, although they had an increasingly important role in an ageing society. As one respondent argued: ”properly trained care assistants would help people to stay at home”.

David was one of the people involved in contributing/drafting/editing/finalising the plan, but he is not the sole author