The lifetime risk of death is 100%. As every Terry Pratchett fan knows, if we do somehow elude cause A, on date A, in place A, the Grim Reaper will probably reschedule soon enough.

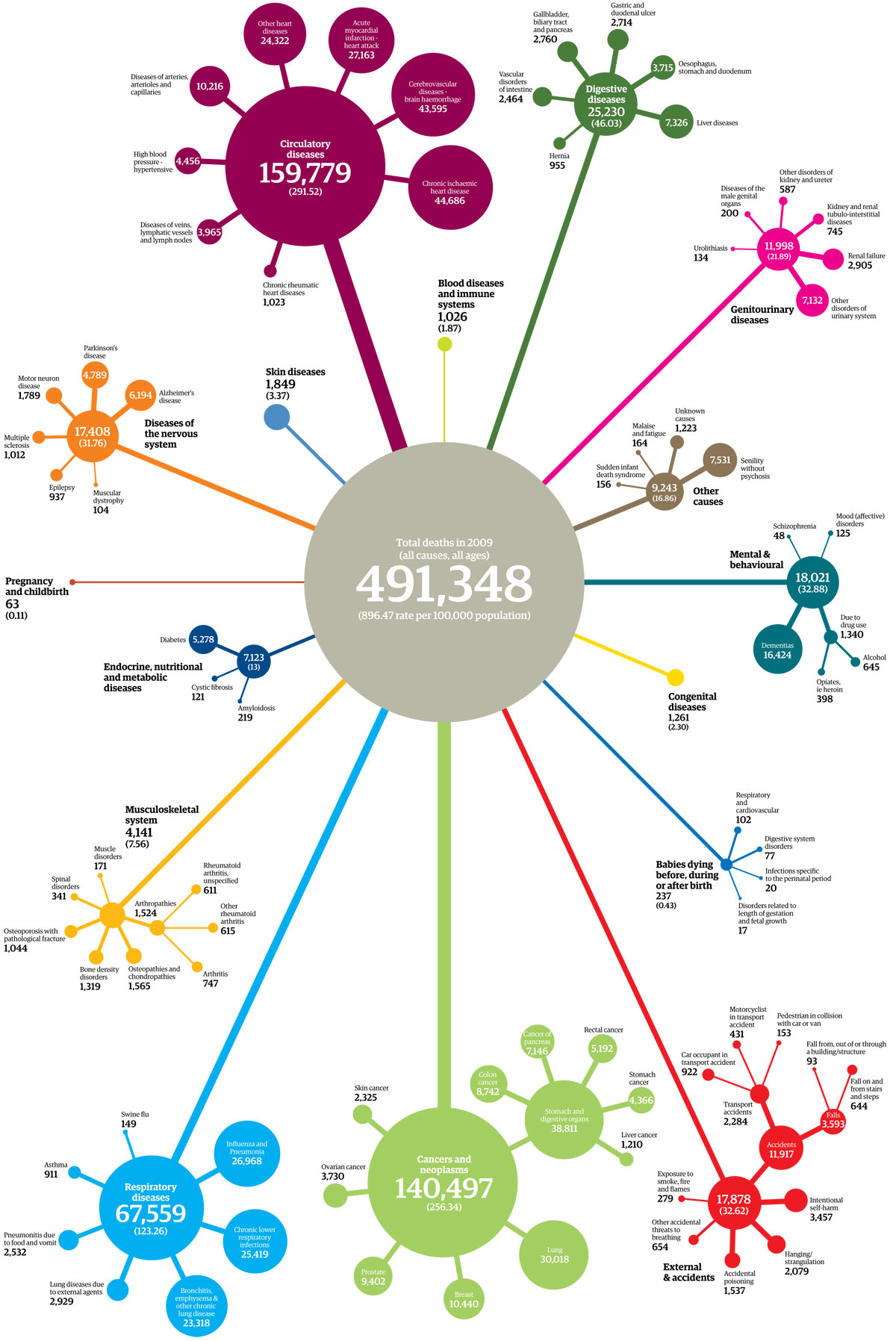

We know the main causes and places of death in the UK, and they don’t really fluctuate much. Almost half a million of us die annually; usually when we are quite old. In this beautiful infographic, our causes of death look almost floral.

Most of us take our last breaths in a hospital bed, succumbing to cardiovascular, cancer or respiratory causes- typically after spending 12.9 days in hospital, and often via an emergency admission.

Some of these deaths might have been postponed if we had had optimal hospital care; relocated if we’d had alternatives to admission; coded differently if someone else had certified us dead; rescheduled if we were ‘hanging on’ for Auntie Vera; inappropriately delayed if we were ventilated against our wishes.

And some of our deaths could have been ‘prevented’ for many years; maybe if we had phoned the Samaritans on that fateful day; if we’d taken our statin/ Bblocker/ ACE/ aspirin; if we hadn’t had the systematic disadvantage which faces poor, black, learning disabled or mentally ill citizens; if we’d managed not to get addicted to nicotine; if we’d been the right age for a vaccine.

If pigs could fly; if we’d tackled social determinants of health; if we’d had a well-led, funded, genuinely evidence based healthcare system. Or if we hadn’t walked under that ladder to avoid that black cat… as that brick fell.

In summary:

Mortality is a whole-population risk. The onset of our final illness is likely to precede our final admission by some considerable margin, and many factors influence when we end up calling 999.

If we really want to know whether service configuration is killing us, we need to use the real denominator: the population, and ONS data about day of death.

Because if the doctors’ reluctance to work ever-harder for reduced pay is linked to mortality, the main victims will be those who never get admitted in the first place.

Use of an artificial (and heavily lead-time-bias-susceptible) moving feast of variably defined “weekend admission” comparison in a series of widely-derided scientific papers would not be my method of choice for this question.

But we’ll never find out.

Which is a real pity.