A repeated claim made by politicians and a justification for the Health and Social Care Act 2012 is that the NHS is ‘unsustainable’ in its present form because the UK’s ageing population is increasing costs to levels that we can no longer fund from taxation. But this is a myth. While the proportion of the population aged over 65 years is increasing in most of the developed world as people live longer, there is no evidence for the claim that ageing itself will lead to a funding crisis. Rather, the NHS funding crisis is due to cuts in funding for the NHS and social services coupled with the high costs of marketisation and privatisation leading to service closures such that NHS funded services including GP services and out of hours services and hospital services are no longer meeting needs.

Reductions in funding and budgets for social services and long-term care and reductions in local authority provision add to the strain on NHS services. The volume of services provided is shrinking and these are not keeping pace with need. The amount spent on social care services for older people has fallen nationally by £1.4 billion (8.0%) from 2010-11 to 2012-13. The number of people receiving state-funded care fell from 1.8 million in 2008-9 to 1.3 million in 2012-13.

According to Age UK, in the three years between 2010-11 and 2013-14:

- Numbers of older people receiving home care have fallen by 31.7% (from 542,965 to 370,630).

- Day care places have plummeted by 66.9% from 178,700 to 59,125.

- Spending on home care has fallen by 19.4% from £2,250,168,237 to £1,814,518,000.

- Spending on day care has fallen even more dramatically by 30% from £378,532,974 to £264,914,000.

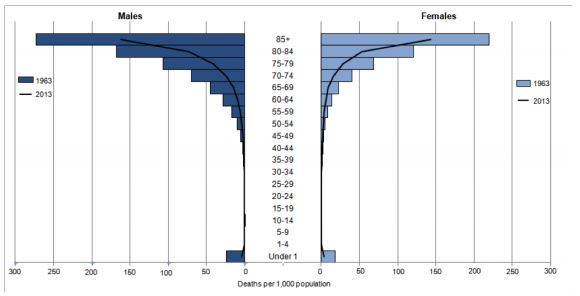

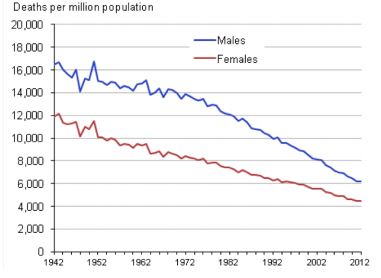

Older people are living longer, healthier and more productive lives

The extent, speed, and effect of population ageing has been exaggerated by the government because the standard indicator—the old age dependency ratio ( The old-age dependency ratio is the ratio of people older than 64 to the working-age population, aged 15-64) — does not take account of the fact that people aged over 65 years are younger, fitter and healthier than in previous decades. In fact older people have falling mortality, less morbidity, and are more economically active than before. Some forms of disability are postponed to later years.

Currently over one million older people are still working, mostly part time, many with valuable experience or specialist knowledge. The spending power of the ‘grey pound’ has risen inexorably. Many do volunteer work vital to the third sector or look after grandchildren.

Older people aged over 65 contribute more to the economy than they take out. It is estimated that taking together the tax payments, spending power, caring responsibilities and volunteering effort of people aged 65-plus,older people contribute almost £40 billion more to the UK economy annually than they receive in state pensions, welfare and health services.

Most acute medical care costs occur in the final months of life, with the age at which these occur having little effect. It is not age itself, ‘but the nearness of death’ or health status of the individual in the ultimate period in the last few years or even months before death that matter most. According to this hypothesis health expenditure on older age groups is high, not so much because their morbidity or disability rates are higher, but because a larger percentage of the persons in those age cohorts die within a short period of time.

Similar findings have been reported in other European countries where by 2008 it was shown that ‘contrary to popular belief, ageing is not an inevitable and unmanageable drain on health care resources.’ Indeed one study suggested that the cost of death declines with age because older ‘people tend to be treated less intensively as they near death.’ In fact, it is those dying between the ages of 50 and 60 who cost the most. If the cost of death declines with age then an ageing society could lead to lower health care costs.

Life expectancy is an estimate of average expected life span, healthy life expectancy is an estimate of the years of life that will be spent in good health. The trend for healthy life expectancy at 65 in England for males and females has increased approximately in line with overall life expectancy at 65. For example, between 2006 and 2009, healthy life expectancy increased by 0.8 years for females and 0.5 years for males while overall life expectancy grew by 0.6 years for females and 0.7 years for males. This suggests that the extra years of life will not necessarily be years of ill health. There are important socio-demographic differences in healthy life expectancy. Not only can people from more deprived populations expect to live shorter lives, but a greater proportion of their life will be in poor health.

When measured using remaining life expectancy, old age dependency turns out to have fallen substantially in the UK and elsewhere over recent decades and is likely to stabilise in the UK close to its current level. It is not age but nearness to death that accounts for health expenditure.

Increased life expectancy means more years lived in good health.

Politicians must stop blaming older people for their decisions to cut funding and close services

The false premises of the ageing hypothesis provide a technical rationale for starving the NHS of funds. In July 2013 NHS England warned of a funding gap ‘of around £30 billion between 2013-14 and 2020-21’. A Lords select committee , the Office for Budget Responsibility , the Nuffield Trust and the Institute for Fiscal Studies published health spending projections on the assumption that ageing is a main driver of cost rises. The studies mainly relied on simple population projections. The connection between ageing and costs and chronic illnesses was simply assumed. They did not consider the fact that people are living longer, healthier and more productive lives.

So the most remarkable thing about the ageing hypothesis or ‘demographic time bomb’ is its survival. The Canadian economist Robert Evans has described it as a ‘zombie theory’, one that refuses to die. It survives today only as a reason for explaining politicians’ bad policy decisions which have resulted in pressures on the NHS: as an alternative to the real reason which is the cutting of health budgets, and services for health care.

In the UK, both the Royal Commission on Long Term Care (the 1999 ‘Sutherland report’) and the Wanless Inquiry (2001-04) rejected the ageing thesis. The 1999 Royal Commission found that, even though ‘the population aged 80 or over is growing rapidly and appears likely to continue to do so’, the UK was not on the verge of a “demographic time bomb” as far as long-term care is concerned and as a result of this, the costs of care will be affordable.’

Wanless concluded: ‘Despite this significant ageing of the population, demographic changes have so far accounted for a relatively small proportion of the increase in spending on health care in the UK. While overall spending (between 1965 and 1999) grew by 3.8 per cent a year in real terms, the demographic changes alone required annual real terms growth of just 0.5 per cent a year. Less than 15 per cent of the growth in health care spending over the past 35 years can therefore be attributed to the cost of meeting the needs of an ageing population. This is in keeping with findings from other countries.’

In Canada the Evans paper on the Romanow report into future health care costs declared: ‘All studies come to the same conclusion. Demographic trends by themselves are likely to explain some, but only a small part, of future trends in health care use and costs and in and of themselves will require little, if any, increase in the share of national health resources devoted to health care.’

The European Commission report of 2010 found that it was ‘the health status of an individual (and – in aggregate terms – of the population), rather than age itself, which is the ultimate driving factor’ behind cost rises. Furthermore, ‘Over time, there is no clear link at the aggregate level between levels of spending on health care and the demographic situation of societies. In fact, several studies have found that the impact of ageing on increase in health expenditures is limited to as little as a few percentage points of this increase.’

The connection between ageing and health care costs has also been rejected in studies and parliamentary reports in the USA, Canada, Germany and Australia.

Examples of the ‘Zombie theory’ and how it is used to justify policy choices:

“We’ve got a growing and ageing population now and this is having a significant impact. It’s down to the policy-makers to decide whether to change the policy or not.” Rupert Egginton, director of finance at the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

“An ageing population with more chronic health conditions, but with new opportunities to live as independently as possible, means we’re going to have to radically transform how care is delivered outside hospitals.” Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England

“However, if the NHS is to meet the needs of an ageing population we need it to be more efficient so it can provide more and better treatments.” Lord Howe, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Health

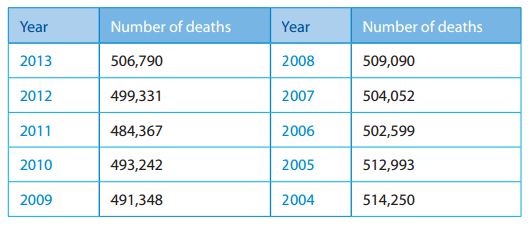

Trends in numbers of people aged over 65 years and mortality rates and number of deaths:

Age structure of the UK: 2011 Census data

- Aged 65 and over: 10.376 million

- Aged 85 and over: 1.394 million

- Total population: 63.183 million

This was first published by the Campaign for the NHS Reinstatement Bill