From what I know about genuine co-production, I do strongly support co-production. I know from experience as a physician and, more importantly, as a patient with various long term conditions, knowing about the beliefs, concerns and expectations of citizens vastly improves care and support, however so defined.

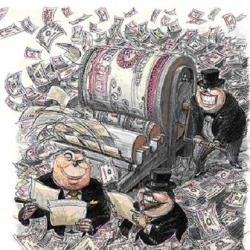

In my other life, in a forced choice between capitalism and socialism, I am a socialist. I don’t as such believe in the faith of ‘kinder capitalism’, though I can see that some capitalism is blatantly immoral.

Market failures loom large on many people’s minds, however. It’s not good enough to embrace socialism merely as a rejection of capitalism.

“The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop to such concerns as U.S. Steel illustrate the same process of industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.” (p. 83)

The notion of economies mutating themselves into fitter versions has been an important one, so much so Paul Mason appears to argue in ‘Post Capitalism’ that this chain of mutations of capitalism may have run its course.

Schumpeter’s ‘creative destruction’ of course has a different angle if you consider that an alternative angle is the generation of ‘social value’ rather than profit – and profit, bastardised as success, is what companies are supposed to optimise.

There is no legal imperative to maximise social value from the Companies Act (2006). Although Schumpeter devoted a mere six-page chapter to “The Process of Creative Destruction,” in which he described capitalism as “the perennial gale of creative destruction,” it has become very influential.

It is conceded that social value can be generated as well as destroyed.

A definition of ‘social value’ can be derived in the context of the Public Services (Social Value Act) 2012 from the last government.

“Social value” is a way of thinking about how scarce resources are allocated and used. It involves looking beyond the price of each individual contract and looking at what the collective benefit to a community is when a public body chooses to award a contract. Social value asks the question: ‘If £1 is spent on the delivery of services, can that same £1 be used, to also produce a wider benefit to the community?’

According to “Social Value UK”, social value is the value that “stakeholders experience through changes in their lives”. And “Some, but not all of this value is captured in market prices.”

Indeed, according to them, Social Return on Investment is a framework for measuring and accounting for the value created or destroyed by our activities – where the concept of value is much broader than that which can be captured by market prices.

My concern is that there seems to be little discussion of the destruction of social value.

Co-production, having stakeholders genuinely ‘in the room’ and co-designing systems and processes from the start, is ‘equal and reciprocal’ from Nesta’s viewing point. Time banks, as created by Prof Edgar Cahn, comprise an innovation genuinely built on reciprocity, fairness and social justice.

But the tension between social value and profit I feel is very important. I think it is possible to reframe this as a conversion from a private limited company from the contributions brought by individual stakeholders for the purpose of generation of profit. In a sense, there is creative destruction of social value to promote profit. This can leave people who have contributed freely contributing value rather abused and ultimately disenfranchised if nothing as such happens with their opinions apart from disappearing in a mass of profit generation into sheer anonymity. This creative destruction of social value is indeed innovative, but actually quite abusive. It can happen with anything, but particularly pertinent to the Health and Social Care Act (2012), is the monetarisation of ‘patient opinion’.

This was brilliant encapsulated in a single tweet by Alison Cameron (@allyc375).

@dr_shibley @TDJeanette @OWigzell Need to address disempowerment & asset stripping that happens when ppl are seen as data sets & no more

— Alison Cameron (@allyc375) April 14, 2016

A definition of “asset stripping” is “the practice of taking over a company in financial difficulties and selling each of its assets separately at a profit without regard for the company’s future.”

Just as traditional capital can be ‘asset stripped’, it is then perfectly possible that social capital and social value are also “targets” of asset stripping.

The repercussions of this comparison to asset stripping are enormous, however. It means individuals’ ideas and experiences can be swooped on and converted to ‘sell at a profit’, without actual regard to the future of the individuals concerned. This is hugely unethical, potentially, if this is at the expense of people in a potentially vulnerable (rather than genuine “empowered”) position, say patients of the NHS or users of social care.

The NHS is of course equally culpable, potentially, of financially abusive behaviour as Alison points out – the example she gives as participants in drug trials, but I think that this can be extended to information contributors for ‘Big Data’ – personal genomics lie at the interface of both?

That of course is not how genuine co-production works. But it might be a way for capitalist economics to survive a bit longer.

At one level, “bad” co-production (which is not co-production at all) is useful marketing for competitive advantage. But another level it is something much less superficial.

Anyone involved in co-production I feel should be aware of this important phenomenon which Alison Cameron has uniquely and originally highlighted for us.

I do not want you to go away with the feeling that I am trying to be destructive about co-production. Far from it. I just don’t think it’s fair for genuine co-production to be tarred by the brush of co-production ‘pretenders’ – that’s all.