“So how much does heart bypass surgery cost then?” asked an elderly gentleman. The hospital where I work (which doesn’t provide heart bypass surgery) was staging its annual open day, an opportunity for the public to gain an insight into the workings of a hospital when they’re not stressed out as a patient or visitor. The chance to meet nurses, doctors, therapists and other clinicians and ask questions. And, for the first time at this particular open day, an opportunity to quiz the hospital’s finance department.

We’d scratched our heads to come up with ideas for a finance-themed stand that would grab peoples’ attention. It was always going to be a struggle to compete with kids bringing teddy bears for a check up in the Teddy Bear Hospital or behind the scenes tours of operating theatres but surely we could come up with something to challenge the stereotypical pen pusher image of the NHS accountant? Eventually we settled on a game loosely based on the eighties game show Play Your Cards Right minus any casual sexism. In place of over-sized playing cards we had six A4 sized pictures representing a hospital procedure or treatment with its cost on the reverse side. For instance, a visit to the hospital’s Accident & Emergency department costs, on average, £142 whilst a knee replacement operation and the accompanying stay in hospital costs more than seven thousand pounds.

The gist of the game was to take each card in sequence and guess whether the cost of a particular treatment or procedure was higher or lower than the previous one. It probably doesn’t sound that enthralling but it generated a considerable amount of interest with many people expressing surprise at how much some aspects of hospital care cost and how it would be useful to make this sort of information more widely available.

In truth, much of this information, in the form of an annual costing exercise called reference costs, undertaken by all hospitals, is already freely available online should you have the time or the inclination to negotiate the Department of Health’s bewildering website. Increasingly hospitals are making use of this information with many now sending text messages to patients reminding them of a forthcoming outpatient appointment and informing them of the cost to the hospital should they miss that appointment.

Of course, this is useful information and it’s undeniable that in such a vast organisation with finite resources that it is important to be aware of costs. But used irresponsibly and with a lack of appreciation for how the information is calculated, or even what it means, it can be damaging.

More than twenty years ago the NHS was set on a road to privatisation with the introduction of a phoney “internal market” with a “purchaser-provider split”. Put simply, this means that each time anyone requires the services of a hospital, as an inpatient or outpatient, a financial transaction takes place that sees a sum of money flow from a “purchaser” or “commissioner” of healthcare to a “provider” hospital. It’s something that relatively few people outside of the health service are aware of.

Since the introduction of the misleadingly titled “payment by results” system in 2003 the “national tariff” or price list for these transactions has been based on the national average costs for “healthcare resource groups”, packages of clinically similar treatments and procedures, derived from the annual reference costs exercise. Thus, in one fell swoop, the costing of NHS services was transformed from being an important task that allowed hospitals to compare their costs to other organisations into a vital component of the marketisation of the health service. At the same time, hospitals were encouraged to become Foundation Trusts, de-coupled from local health authority control and run as largely autonomous businesses. Suddenly business jargon such as EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation) became part of our daily lives as NHS finance managers and we increasingly began to focus on balancing the books of our own organisations with competition, rather than cooperation, the name of the game.

A hospital isn’t a factory churning out widgets. Apart from a small number of routine procedures such as cataracts and hernias that can be performed as day cases, and are often cherry picked by the private sector, the costs for the same procedure can vary significantly for different patients. Take someone rushed into A&E and subsequently admitted with a urinary tract infection for instance. The difference in the length of stay and costs between a patient who is otherwise healthy and an elderly patient with advanced dementia and other complications can be huge. Each patient who enters the doors of a hospital represents a unique challenge to the nurses, doctors and other staff whose job it is to care for them. The wonder of the NHS is that none of these patients should have to worry about the costs associated with their treatment.

Aside from headline grabbing expensive new medical technology and life saving drugs our health system is fundamentally about people looking after people. It’s about care, compassion and kindness; a labour-intensive process that means that around two-thirds of a typical hospital’s budget is spent on staff costs. In addition, much of what we refer to as healthcare is delivered outside hospitals and tends to pass unnoticed, almost invisible. Labelled as “social care” and no longer free at the point of access, it is seemingly an inferior form of care. Yet how do you put a price on the tenderness and love shown to elderly people with dementia by husbands, wives, partners, sons and daughters? And the care provided by care assistants paid a pittance to help patients perform simple daily tasks such as getting dressed and going to the toilet? Or what about the burden placed on families of looking after a mentally ill teenager?

The simple answer is, of course, that you can’t put a price on such forms of healthcare. But after more than two decades of relentless marketisation and lauding of the private sector those in charge of the NHS appear reluctant to grasp this fact. Some types of healthcare, usually planned and routine forms of treatment, can be relatively straightforward to cost. But it’s clear that most healthcare is often complex, difficult to diagnose and does not lend itself easily to having a price tag attached to it. The difficulties in costing mental health and ambulance services are evidence of this; payment by results for mental health services was introduced ten years later than acute hospitals.

The NHS was established to meet clinical needs and should be a section of society that is effectively closed off from market ideology. Costing does have an important role to play in the NHS but used merely as the basis to prop up a phoney market system is a waste of resources and an insult to those NHS finance staff who take as much pride in their work as the nurses and doctors that they support. For twenty five years market reform of the NHS has been the only game in town but it has generated little discernible benefit for patients and costed billions to implement.

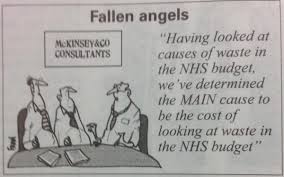

As someone who has worked at the heart of this market place for more than twenty years, I’m tired of the near obsession with generating so-called efficiency savings; of hospital Trusts desperately trying to protect their “revenue streams” and maintain financial viability; of the relentless paper trail of reports, documents and invoices that support contracts between “providers” and “purchasers”; of clinical commissioning groups protecting their own financial positions and looking for reasons not to pay invoices; of the language of business being applied to something that is most definitely not a business; of allegedly focusing on “waste” whilst at the same time spending millions on management consultancy and of sitting through endless meetings where there is barely a mention of the patients that we care for. At what point will we realise that not everything in life can be reduced to a number on a spreadsheet? Stuff the need for everything to be “fully costed” where’s the passion and dynamism that established the NHS in the first place?

In the midst of the most important election ever for the future of our NHS, the poverty of the debate about the funding of the health service is, at times, astonishing. Too often the NHS is described as “unaffordable” when it was perfectly affordable amidst the ruins of the second world war. Not for the first time there are calls for charging for some NHS services such as GP visits or A&E attendances yet there is barely a mention of the billions spent on propping up the “internal market”. A 2014 report by the Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI) estimated that the costs of the internal market (with its need for contracts, billing, costing, activity data, computer systems, legal advice etc) at a conservative £5 billion per year. A more likely figure of £10 billion has been suggested by the National Health Action Party. And this ignores the one-off costs associated with repeated reorganisation and restructuring. The bill for implementing the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 is estimated at more than £3 billion. These are staggering sums of money (as much as 10% of the total NHS budget) that are barely mentioned in any debate around the affordability of the NHS. But this is not surprising given that both of the main political parties have been instrumental in this marketisation process; the Tories established the market in the early 1990s and Labour reinforced this a decade later with the introduction of payment by results and Foundation Trusts.

Returning to the question posed at the beginning of this piece; the national average cost of heart bypass surgery (or coronary artery bypass graft surgery to give it its proper medical name) in the 2013-14 financial year varied between £8,632 to £15,121 per hospital spell according to the degree of complexity involved. These figures include not only the costs of the operation itself but also the costs of the accompanying stay in hospital, often for seven days or more. The costs of doctors, nurses and therapists are added to the costs of a ward stay such as meals, heating and lighting, cleaning and also the overhead costs of running an NHS hospital (including the finance department) to come up with a total cost. It may sound a lot for one patient but it’s difficult to put a price on the difference that it can make to someone’s quality of life. More than twenty thousand of these procedures are performed in England each year. Let’s hope that we can find the collective heart to preserve our NHS so that life changing treatment such as this remains accessible to all, free at the point of access and publicly provided by the best health service in the world.

First published on Jonathan’s blog Nowt Much to Say