Background

For thirty years (from June, 1982) I worked in Manchester’s services for people who are intellectually disabled (usually termed learning disability in the UK, but nowhere else). I worked as a practitioner, a developer of services, a researcher, a head of professional services and ultimately (for 8 years until March 2012) as the manager of integrated health and social care for learning disabled adults. My commitment to work in the city of Manchester was complemented by national and international networking that helped me to take a wider perspective on the peculiarities of what we did locally and also how our British systems functioned.

Over that period spanning three decades, we saw the shift from institutional care, the development of community-based supports and the person-centred approach, the impact of marketisation and the beginnings of austerity. In 1994 we established an integrated service where the local authority and NHS elements were managed under what became a partnership under the Health Act (2000). I was part of the management team for the combined provider and there were complementary agreements on joint commissioning and a pooled budget (although on the provider side, for the most part, we managed the budgets of the two organisations side by side, within the overall pool). My comments then reflect my history, and in particular experience in managing a public service, to adults with all levels of intellectual disability (including very complex combinations of need), and as a provider.

The principal challenges we faced with this pioneering model, in terms of the operation of the overall system, were,

1) Problems influencing the wider health care system, in particular General Practice and acute hospital care to respond appropriately to the combined needs of the people we supported. This was amplified by a general disinterest in our models from the mainstream health and care system, which tended to see it as irrelevant to their activity.

2) Colonisation of the person-centred approach by a consumer-commodity-market model (analysed in this article).

3) Constant pressure to reduce costs, via privatisation of parts of the service and paring those elements that supported quality (hand-overs, team meetings, training and education and so on).

4) Imposition of performance targets that bore little relation to the realities of service delivery and which distorted and distracted.

5) Professional resistance to the more radical integration of skills and care pathways that would supplant multi-disciplinarity with inter-disciplinary practice (and in so doing introduce some efficiency gains and a more person-centred approach).

6) In social care, the dominance of the “assess-and-place” production-line model of elderly care, especially problematic with the adoption of organisation-wide electronic assessments and case records. This militated against longer term relationships grounded in a problem-solving, capacity seeking, co-production.

7) Pressure to split off functions that should be closely connected into seperate divisional arms – e.g. domiciliary and short term support functions separated from “assessment and care management”; separation of social work and community health professionals from “commissioning”. (Similarly the Dobson innovation of Primary Care Trusts was a missed opportunity for integrating commissioning, public health, primary care and community health provision, squandered in part by a lack of imagination at local level and then scuppered by New Labour’s return to the market under Milburn and Hewitt).

8) Marginalisation of learning disabled people and their families from decision-making about the system as a whole.

Why do it?

Integration is a good thing because people’s needs are indivisible. Those who have everyday support needs (for what we call social care these days) are also likely to have significant health problems, and the two interact. Failing to meet a social care need creates health problems, but neglect of health issues creates further need for social support. Thinking through how to make such integration work requires us to simultaneously keep the following things in our view.

1) Before even thinking about service integration, or even about services, we need to reflect on the “problem” that such services are there to fix. This is a more fundamental question than the technical arrangements for inter-sectoral integration and it goes to the heart of what social policy is about. Elsewhere I have contrasted three models of social policy, the neoliberal, social-democratic and convivial. But let’s concentrate on the narrower question of health and social care integration. For people who are intellectually disabled, I have put it like this, but the same thing could be said for other categories of need:

For those of us who are striving to improve supports for intellectually disabled people there are many potential things on which to focus our attention. However, the one that affects all the others is the persistent and systemic disadvantage that intellectually disabled people face in all societies. It cannot be fixed overnight, but requires long term effort, strategy, and let’s be quite clear about this, struggle. It is this disadvantage that underpins the problems of poor health care, abuse and the need for high expenditure from our economies that otherwise have little space for those who are perhaps the most disadvantaged of all. In my view we need to keep this problem of systematic disadvantage at the centre of our attention and frequently return to it in order to set direction for the more specific and concrete actions and initiatives without which the overall aim of reducing disadvantage is no more than a vague aspiration

Provision is not (only) a technical matter, it is about basic morality. The draft LB Bill, which proposes the presumption of social inclusion, is one practical initiative based on similar thinking.

2) Meeting the complex of health and social needs requires an approach I can only describe as “dialectical” – overcoming opposites through a synthesis that transcends them.

So it is necessary to:

- Understand need as ordinary and existential, about social justice and freedom from oppression, while at the same time involving specific knowledge about illness and disability and how to treat and ameliorate it. It is not a matter of adopting a social model that precludes the medical, but of adopting a social model that includes effective health care, refusing to romanticise people who in some cases may be difficult to be and interact with and who can be difficult to help and support. They are nevertheless the essential partners in any authentic system for meeting need.

- Avoid the separation of health and social care and support, but not reduce one to the other. There is a need for specialisation but that does not imply separation.

- Focussing on the integration of health and social provision should not mean the neglect of other areas of life. One of the strengths of the 2000 White Paper Valuing People, was its emphasis on going beyond health and social care, seeing that people’s lives involved other sectors too, from housing and leisure to primary care and the justice system. This implies a redesign not just of specialist health and social care, but the entire system of public services, in the context of a revitalisation of our communities as social systems that have a valued place for everyone. Any solution to these complex issues has to go beyond “services”, whose reform needs to be understood as part of a wider effort of societal transformation for economic and social justice.

Other considerations

Dependence, independence, interdependence.

There is much foolish talk of increasing independence. In the vocabulary of the disabled people’s movement, that word has a positive meaning, of freedom from control by professionals and non-person centred services, still all too common. But in neoliberal hands the word has an ideological function, supposing human beings that exist in a vacuum, as individual atoms, units of labour and consumption. That latter usage denies our interdependence, and proffers the fantasy of converting people who do depend on the support of others, into independently living units, able to work and consume. In accordance with the neoliberal myth of independence, wildly optimistic scenarios of reducing dependence have been sketched, as managers try to adapt to greatly reduced budgets.

Instead, a new settlement for health and social care needs to use the concept of “just the right support”, predicated on the assumption of human interdependence.

Efficiency

Waste is not a socialist value, but an over-emphasis on efficiency means a host of shortcomings including the devaluing of staff with poor terms and conditions, skimping on training and education, and services that are running to keep still with no time to reflect and plan collectively. Ultimately it means a focus on the money rather than the people – a recipe for further care scandals.

IT systems

Good systems for organising the work are necessary but they must follow rather than determine the pattern of care. The opposite has been seen in the adoption of digital case management systems that impose inadequate and uni-disciplinary assessment and care planning approaches. Andy Burnham’s emphasis on listening to the people at the grass roots is welcome here, since staff generally understand what the job actually is that needs supporting not obstructing by digitisation.

Protecting and improving quality.

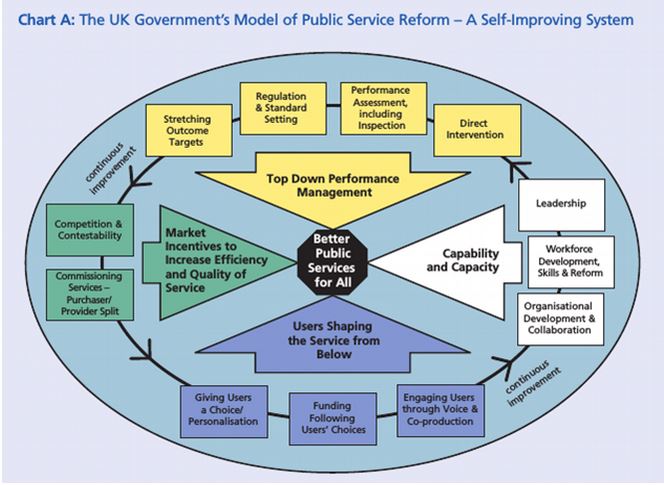

Assuming that there will still be a mixed economy, at least in what has been social care, there is a need for a more effective approach to quality protection and improvement than the undemocratic, market-based model imposed by neoliberal New Labour (see illustration).

In my experience, the greatest improvements happen when there is an active search by staff, managers and those affected (people using services, their families and their advocacy organisations) for improvement, based on a shared vision of inclusion and what it takes to make it happen.

Local variation

One size doesn’t fit all. This means that the solution for a learning disability service in Manchester is unlikely to be appropriate for one supporting elders in Shropshire, or people with mental health issues in Stoke. This makes it vital to identify clearly the underlying principles and allow creativity in applying them. A further consideration is the increasing phenomenon of overlapping needs, in individuals, families and communities. Despite having been a specialist service provider, I can see arguments for connecting generic and specialist elements, avoiding duplication and dis-coordination.

Money

Under present arrangements, the social care sector is under far greater financial pressure than the health sector. This means that if integration takes place under conditions of continuing austerity and without a new settlement, there will be unplanned and unacceptable raiding of one sector to prop up the other. In the Manchester Learning Disability case we avoided this through incomplete pooling of budgets – the separate budgets were instead aligned and managed by the same team. However the additional strains after the Tory cuts to local government from 2010 meant the effective collapse of the partnership and dismantling of much of our 30 years’ work. This, and the earlier collapse of similar voluntaristic arrangements in a handful of other authorities should advise caution on going into integration without a solid financial basis. The experience of the Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust was similarly bedevilled by what, from the outside, appears to have been a bodged financial foundation.

Andy Burnham notes that perhaps the main reason for public support for the NHS is its establishment on the principle that human need trumps narrow economic rationality: need over money, This is the case at both the individual and the societal level, the principles of risk pooling and social ownership connecting the two. The principle needs unequivocally extending to the social care side of the equation, for without that there will always be an imbalance, and hence “burden shifting”: pulls and pushes that have nothing to do with meeting need. Yet while government continues to promote the erroneous notion of balanced budgets and the elimination of government debt, then the scene will be set for an system beset by budgetary crises. Government needs to set out its priorities, create the money to fund them, and manage the consequences through taxation ( See for example Guinan, J. (2014). Modern money and the escape from austerity. Renewal, 22(3-4), 6–21)

Mark H Burton

Scholar-Activist, Visiting Professor, Manchester Metropolitan University