This is the sixth revision, taking into account comments made by members on the earlier version. Proposed to be adopted at the 2014 AGM.

Introduction

We set out our response within the context that there will be a restoration of support for public services and an end to the era of emphasis on privatisation, marketisation and market competition. The social and economic value of good quality public services should be emphasised as should the dedication and contribution made by the care workforce.

We strongly support the vision of a care system which begins from understanding and dealing with the social determinants of poor health and which has as a founding value the need to demonstrably reduce inequalities of all kinds, especially in health.

We support a comprehensive universal system for care free at the point of need, paid for out of general taxation and contributing directly to the redistribution of income and power. Entitlements to care must be clearly defined nationally and with a Secretary of State legally and politically responsible for the provision.

We believe there is a wide consensus about what a good care system would be like and a shared desire to achieve that objective. But it will be very difficult to make the transition to what will be a different system, designed to meet current needs and far more work is required to map out how such a transition might be achieved. We believe that Labour should:-

- Share a new vision for what a whole person care system should be like – viewed through the eyes of those who will be using it.

- Publish a 10 year plan to move decisively from where we are to where we wish to be.

- Set out how to accelerate the pace of change as economic conditions improve with quality services ranking ahead of any tax cuts

- Ensure an emphasis on quality – of outcomes, safety and experience of care

- Support those who work in the care system, including those who manage it, giving a clear sense of direction

- Ensure that those who work within the care system have decent terms and conditions within a national framework and emotional support leading to better care and compassion

- Ensure that planning for wellbeing takes place on a population basis with a key role for local authorities in bringing public services together; at different rates in different localities (Labour councils can take the lead on this)

- Promote removing legal, structural and financial obstacles to cooperation, collaboration and partnership working

- Encourage and incentivise innovation in how services are delivered but within a clear national framework which sets out entitlement.

- Propose a few immediate changes, but without any kind of whole system top down reorganisation. Keeping to an absolute minimum changes that are imposed by directives from the centre.

We also believe that radical change is most needed within social care. We support moving progressively to a system where all care becomes free at the point of need. Even within current funding arrangements it is essential to ensure higher standards of care and more equitable access to care for all with moderate needs. We would argue for the case to be made to fund the cost of such changes by increases in redistributive taxation – with tax on forms of wealth as a candidate.

At the earliest opportunity we need to:-

- Acknowledge the key importance of the social determinants of poor health and plan how best to deal with them across the whole of public service

- Remove from the NHS the whole paraphernalia of markets and competition; restore the powers and duties of the SoS to ensure we have a universal comprehensive NHS.

- Increase the funding for social care; moving the workforce onto a proper set of terms and conditions; setting an appropriate national level for entitlement to care; set out a long term approach to social care funding.

- Shift from commissioning that is used to support a market with competing providers to planning how best to use all the public resources to get the greatest health gains for defined populations.

- See patients and communities as strengths and assets – experts with whom professionals share decisions and planning.

1) Whole Person Care/ Integration of health and social care and mental health

1.1 Whole Person Care (See Appendix A)

- We need a care system rather than separate systems with a vision for whole person care as viewed from the personal perspective and as described by National Voices.

- We also see the need for integration between sectors in the NHS to remove barriers between for example primary and secondary care. And also between social care and health.

- Individual shared care plans should be used to improve the support and treatment of people with long term conditions.

- We would extend the concept especially to include housing. Locally this should also reinforce the requirement on local authorities to ensure the wellbeing of its population through integrated public services.

- We do not accept that integration of itself automatically produces significant savings. Nor do we yet support full budget sharing between health and social care. Better integration can also be achieved through other means than merged budgets.

1.2 Moving to free personal social care funded from taxation

- A barrier to whole person care is that social care is funded differently, structured differently and means tested.

- The case for free personal social care is exactly the same as the case for free health care, and in other parts of the UK this has been recognised. The risk of high costs which are not predictable and which cannot be insured requires a form of social protection.

- There will be savings from moving to free care (especially through reduced bureaucracy and administration) and outcome improvements through easier integration of services. Over time better social care reduces healthcare costs, but the net cost has to be met – probably through progressive general taxes as with healthcare.

- Issues of inter-generational fairness but also inter generational solidarity arise.

- A start can be made by the state meeting all costs above a certain limit and making care free for some such as those who have disabilities.

1.3 Social care system

- The most important change is to fund social care properly so the quality of care is everywhere appropriate.

- The NHS Constitution should be widened to cover all care.

- Social care should be seen more widely than the emphasis on older people.

- The subsidy implied by the unpaid labour of family and friends should be acknowledged with an explicit “fair deal for carers”, giving them rights also.

- We support the need for a properly skilled, motivated, well managed and properly remunerated workforce with those employed as care providers on some system like Agenda for Change.

- We support structural integration as part of the move towards cultural and behavioural change; and where this will deliver economies of scale and more rational investment incentives.

- Assessment of needs is complicated and requires safeguards, but we support the principle of a single national portable assessment process suitably informed by shared decision making and advocacy.

- Care planning must cover housing and environmental needs.

- We support the general principle that standards and basic entitlements are set nationally, and this is monitored and enforced. We support the principles around NICE and see that as extending into social care, probably through SCIE.

- The principle that entitlement is set nationally but delivery is determined locally must be tempered by the need for some genuine local autonomy, to make local democracy have greater meaning.

- Structures and systems for provision should be decided locally and we may see different approaches in different settings. Local authorities are not generally subject to top down enforcement as NHS bodies are.

- A personal budget may be suitable for some – but there can be no compulsion or even direction.

- We should remove the ambiguity around top ups and move towards a clear separation but the quality of care should be such as to make this less attractive and unnecessary.

2) Making our NHS a genuinely national system

- The N in NHS requires national standards, national service frameworks, national outcomes frameworks and inspection and regulation on a national basis.

- What defines the “comprehensive” nature of the NHS is defined nationally and guaranteed by the Secretary of State. The SoS can intervene if there are serious departures from what the NHS should be delivering.

- The rules which determine how the NHS approaches issues around cooperation, procurement and competition should be binding throughout the NHS.

- National terms and conditions for staff should apply so staff can move within the NHS. although there can be the kind of flexibilities Agenda for Change already provides within the same overarching national framework agreement.

- Revenue funding should derive from a national formula based on weighted capitation; we need to go back to a geographical basis. Programme funding which is aimed at specific outcomes rather than at organisations can, as now, be controlled at the appropriate level most usually national or regional.

- There are strong arguments for national shared services and some national procurement framework to lever in economies of scale.

- We already have national systems for collection of data and we must have an obligation on all providers to supply that information with proper sanctions – we need high quality comprehensive data.

- This national service must however be tempered by patient and public involvement and if we are genuine about being responsive to local population need, then there will of necessity be differences in local planning. So long as the differences in area provision are properly explained and seen to be logical, it is no longer a lottery, but evidence of responsiveness to local need.

- This balancing act requires the SoS to have ultimate responsibility for securing the provision of services and power to intervene in any part of the NHS and to issue binding directions – although they would only rarely ever use such powers.

3) Repealing the Health and Social Care Act 2013

3.1 Competition and the internal market

- A model for the NHS based on regulated internal and external markets and economic competition between providers is rejected. The apparatus of the internal market should be progressively dismantled. The emphasis should be on a system to support and further social solidarity.

- Relationships between commissioners and providers should be within the NHS and not the subject of legally enforceable contracts.

- It should be a matter for commissioners[i] to decide how best to secure the provision of the necessary services but only within a very clear national framework.

- Nothing in domestic or EU law should be able to compel a commissioner to end an existing relationship with an NHS provider or force competitive tendering of clinical services.

- Where a commissioner is unable to secure provision of the necessary service from an NHS provider to the required level of quality then they would be expected to look beyond the NHS and run a competitive process.

- Where private providers are used the contract duration should be minimised and clinical knowledge and experience should not be lost to the NHS.

- Commissioners would be expected to test the quality and efficiency of all services on a regular basis to be able to demonstrate value for money and “best value”.

- The Competition Commission should not have any remit over NHS services and NHS providers would be free to merge or otherwise make strategic arrangements without external interference, subject to some form of local agreement. The Independent Review Panel and could be retained to give local advice short of recommendations.

- We support greater access to information but not as a market enabler. We support the principle of NHS data must be used to benefit NHS patients. If data is acquired by a third party it must be on an understanding that the NHS retains ownership of that data (and can withdraw it, under certain circumstances)

- Any commercial products resulting from that data should be made available free of charge to all NHS providers.

- We believe the separation of commissioning from provision to facilitate a market should be reversed. We support the ideas around a planned public service not a market.

- Many of the functions included within commissioning around needs assessment, pathway design, planning of services, setting of required standards, ensuring continuity of provision, and the monitoring of performance and quality are important and have to be done somewhere. These functions should be carried out separated from provision because:-

- Planning for improving care should cover more than just the providers

- There has to be some strategic layer than allows resolution of the wicked issues like reconfiguration where there will be winners and losers

- Acute providers are always dominant and Community Care, Mental Health and other “Cinderella” services lose out

- Too many “providers” have vested interests (especially GPs).

- There are also potential issues with retaining separation that have to be addressed.

- Lack of transparency

- Lack of accountability

- Blurred responsibilities with endless passing the parcel

- Gamesmanship & game playing — particularly over resources

- The expertise which resides within providers needs to be captured to help inform service design, pathways and specifications but they should inform the decision making processes not take part directly in them.

- Care resource allocation at every level is based on judgement and supported by evidence and professional advice and must balance what will often be competing priorities and even local politics. Those who make the key decisions about how resources are allocated and about how priorities are set within a tax funded, cash limited, system should be elected.

- There must be one single democratic body which oversees the whole of the commissioning of publicly funded services for a locality – usually a tier one local authority or a grouping – for example a pan London body.

- Clinicians, especially GPs (who have greatest contact with patients), must be closely involved in pathway design, service specification, monitoring quality and outcomes, but generally on a part time basis or as required.

- The more transactional aspects of commissioning around data gathering, procurement, contract management, invoicing, and other back office functions which are continuous need to be carried out by others, but still within the NHS and not outsourced.

- The longer term goal is for integrated commissioning undertaken by the local authority which looks across the whole public sector, driven by the local strategic needs assessment and set out in a wellbeing strategy and commissioning policies, all of which are informed by public health.

- We support making the environment conducive for integrated provision where this can be evolved without major structural upheaval through incentives for joint appointments, joint budgets, collocation, information sharing, and shared services across the NHS and local authorities. Initiatives such as “year of care” and “programme budgets” must be encouraged and coupled to incentives for joint working.

- The Authorisation process for CCGs should continue.

- There should be a single body (Special Health Authority) responsible for all specialist commissioning – possibly with sub regional outposts.

- The total budget for specialist commissioning should be agreed in the overall plan and then passed to the SHA for allocation.

- The Board of the SHA should include independent non executives and there should be a Clinical Steering Group.

3.2 Commissioning[1] (See Appendix C)

3.3 Specialist Commissioning

3.4 Primary Care Commissioning

- Primary care commissioning should take place locally not nationally.

- To avoid conflicts of interest the CCGs’ governance should be altered to have non- executive directors and/or public and patient representatives in the majority.

- Primary care should increasingly be seen as a resource to be harnessed for the community. For instance, using the buildings for community groups.

3.5 Public Health

- The political narrative on public health and the NHS should centre on the health and well-being benefits of tackling social inequalities, linking to the practical vision of economic development with productive jobs, real innovation and locally-based investment.

- We should support and strengthen the move of public health to local authorities. The key test of public health devolution will be ability of local authorities and local NHS to manage change, working across institutional boundaries. Public health funding needs to continue to be ring-fenced, at least until the habits of collaboration are well bedded in.

- Each Local Authority must have a qualified Director of Public Health reporting directly to the Chief Executive and with protection of the sort offered to Section 151 Officers. They should be professionally responsible to the Chief Medical Officer who must also approve all appointments and terminations.

- Over time all public health staff and budgets should be independent and managed through a strengthened Public Health England, whilst professionals would continue to work within both local authorities and health bodies.

- CCGs with boundaries that do not correspond to the other agencies involved in public health are not sustainable. Uniting health and social care around the local authority platform will give planning for health real muscle.

3.6 Patient and community voice

- We strongly support complete openness in the provision of information to support patient voice; no NHS funded service or body should be exempt in any way from FOIA and commercial confidentiality should not be used to block access to information.

- Communities should be involved in the planning and commissioning of their services with a major say in how to improve the health of their locality. Decision makers must be obliged to make this a reality and should be monitored on the effectiveness of doing so.

- We should firmly embrace the importance of community development which works with communities as assets not as problems. Asset-based community development approaches need to be highlighted and promoted. We need communities to take more control of their environments and work closely with statutory agencies through residents-based partnerships.

- We should make involvement in our individual care a reality by embracing shared decision-making and self-care. In general patients want greater involvement in their care and they should be offered informed choice about the treatment options open to them.

- Patients should have the right to see whatever information is held about them and should have access to independent, but quality controlled information about their condition and their options. But some will not want to be proactive and just wish to be guided, advised and supported; they should not be coerced into anything.

- In many cases, once their care plan is determined, patients should be able to choose which NHS venue they attend and should be able to select the appointment that best suits their needs. These are not market choices and the likelihood is that the vast majority will be guided by professional advice and also are likely to choose facilities in the locality.

- We should bring back the best features of Community Health Councils and embed within Local Health Watch bodies with adequate support and guaranteed funding.

- Transparency and feedback need to be enhanced.

- There is no need for an economic regulator as the market system will have been abolished.

- There remains a need for some form of registration and authorisation. Monitor should be abolished along with the market structures and with any residual roles moving either to the CQC or to sub regional teams.

- All Trusts should move to the Foundation Trust (FT) governance structure.

- There must be greater clarity about the roles of patients, public and staff within the stakeholder governance structure of FTs where they have influence over decision making and how sits alongside other structures for effective public and patient involvement.

- FTs that do not effectively embrace stakeholder governance should be encouraged to do so; some changes to FT governance rules should be made for example giving governors rights over attendance at all meetings and access to information.

- All barriers to integration through structural change (such as mergers or strategic alliances) should be removed although, in the short term, there would be some authorisation step.

- Integrated providers would require a very different funding approach – probably a single block payment based on population. This would save a significant proportion of the overheads compared with the quasi market with its multiplicity of transactions between commissioners and multiple providers.

- We support the progressive development of broader based integrated NHS providers; a trust as a structure just for a single hospital or a narrow set of services ensures fragmentation, complexity and bureaucratic costs.

- In some localities integration of provision may be achieved without organisational integration through forms of partnership and other arrangements where various bodies agree to work together on a common strategy.

- Integrated providers should be supported and incentivised in the short term by a sub regional structure under NHS England (build on current Area Teams)

- We do not believe that more regulation will in itself avoid future problems. The role of the CQC is currently flawed as it sits within the market structures and is largely a waste of money.

- But one argument to refute any perceived failings of a ‘monopoly public service’ is to show that there is openness and transparency and also regulation and inspection with real teeth.

- Local monitoring of standards based on peer competition, openness and transparency to facilitate “public audit” is a more productive way forward. Commissioners should take more responsibility for the quality of services they are paying for. Staff must be well supported and enabled to reflect on the experience and complexities of caring.

- Royal Colleges should publish quality standards, which set benchmarks which are very useful for lay assessors. Lay people need some support in understanding what they are looking at, and if such standards are comprehensible they are useful for patients too.

- Peer review is also needed as is increased use of clinical audit within and across providers.

- The clinical professional bodies should collectively agree on how they can adapt their practices, training and professional development to meet the new challenges posed by revalidation, appraisals, Community Development and Shared Decision Making and the information revolution.

- They have also to confront some of the messages from the various enquiries which show that their role in ensuring high standards and enforcing best practice is inadequate.

- We should revive the National Service Framework approach. This emphasised clinical collaboration and evidence-based practice and was well respected by the public, clinicians and organisations such as NICE.

3.7 Providers and Regulation

3.8 Reinvigorating professionalism

3.9 Enhancing the status and role of primary and community care

- Moving care closer to home and reducing admissions to hospital through system management and prevention is better for patients and may in some cases also be more efficient.

- Investment in primary and community care is a prerequisite of such change. There is a need for better access (potentially 24/7). Many additional requirements on GP Practices require different working practices, improved premises, better IT, more nurses and health visitors.

- Local primary and community care, providing a wider range of traditionally hospital-based services, are key to improving outcomes and equity, but still with support to access hospital care when it is needed. This may need a review of the GP “gatekeeper” role.

- The small business independent contractor status for GPs may no longer be appropriate for high-quality integrated care. As the patient becomes the centre of integrated multi-disciplinary care, we may need a clinician whose orientation is centred on the patient not the practice.

- There should be more GPs directly employed within the NHS. We should encourage other organisational models whilst still supporting the traditional practice model.

- As in other parts of the NHS, primary care quality needs to improve, driven up by transparent, good clinical and patient experience data, peer pressure and negotiation.

4) Promoting Good health – Prevention and early intervention

4.1 Preventative Health Services

- Improving health requires addressing the social determinants of poor health of which income inequality tops the list.

- Addressing these issues needs to be based on the principle that there is a role for an interventionist state, for redistribution of wealth and power and a role for public services not just in planning and commissioning but in delivery. We need a collective approach.

- Community building/development should be supported as it strongly supports health protection and resilience

- There is now a strong economic argument, particularly in a recession, for increased investment in public services rather than cuts. We need to make the case for investing in a way that will offer the most benefit in terms of jobs and health gain.

4.2 Sugar & Salt Consultation /Helping people make informed choices

- We support helping people make informed choices but we reject the narrative that always looks to put blame on those who need help.

- We reject an approach which presumes poor life choices are due to some character fault – we support looking at the social determinants of poor health and of the causes of poor health.

- We support the widest interpretation of whole person care to encompass as necessary families of all kinds.

- It also applies to children not just older people and the issues around whole person care for children would naturally have to extend the system wide approach into education and other services.

- We support the approach adopted by NICE and would like it to be unambiguously stated that a patient has a right to any care than is approved by NICE.

- We would like to see NICE extend its remit into social care.

4.3 Joined up services for children and families

4.4 NICE

5) Reconfiguration of Services

5.1 Reconfigurations

- We support the principle that changes in service configuration should only be made after adequate engagement and consultation but we believe this to be a process rather than a one off set of events based on some imposed external rules or legal framework.

- Providers and planners should maintain a proactive ongoing dialogue with patients and communities.

- Progressively better stakeholder governance within providers and greater democratic accountability over planning and commissioning should be the basis on which services changes are developed

- We reject the concept of unsustainable providers – no single part of the system can be regarded as an autonomous separate organisation – reconfiguration must be on a whole system basis.

5.2 Changing role of hospital services – community based care

- We do not support the concept of a hospital as an organisation competing with others.

- Hospitals should be seen as valuable assets; as part of a whole system and could be as much a base for primary care as a setting where acute care takes place.

- Staff based at hospitals should also where appropriate be asked to work at other venues within NHS.

- We support moving care closer to home, out of hospitals, but hospital capacity can only safely be reduced once adequate alternative provision is already in place.

- We do not support any form of failure regime which is a market solution for a challenged service or organisation. Avoiding failure is best achieved if the system allows support and assistance from other parts of the NHS.

- To avoid the natural suspicion of communities to changes in local services a system for more inclusive longer term planning with communities is required based on safety, access and efficiency and also on the idea of whole system benefit.

- Professional bodies must be more open and explicit about the requirements for safe care and openness and transparency about financial reporting so evidence informed decisions can be made.

- We expect hospitals to increasingly work with local communities and existing third sector groups.

- We support 7 day working, so long as it is adequately funded and does not remove services from other areas.

5.3 Emergency Care

- Models for dealing with emergency and urgent care will differ depending on the locality and sparsely populated rural communities need a different approach to urban areas.

- We support the need for A&E Departments to have 24/7 facilities to deal with all medical and surgical emergencies on the same site, meeting the many Royal College standards.

- Outside A&E departments there should be a primary care system for ensuring those with urgent needs get the response their condition requires.

- The current failing system which deals with emergency and urgent care is a clear example of how breaking up the NHS and fragmenting it into multiple competing providers does not work.

- Effective emergency and urgent care needs an overall architecture which can only be possible if there is some overall system design and development – and having some loosely defined “network” which does not control the funding or the performance is not enough.

- We need a single NHS body clearly responsible for securing provision of all emergency and urgent care outside of the A&E for each locality. This works only with a single system for assessing the required response; ensuring patients go to or are taken to the best place to meet their needs regardless of how they choose to communicate their need.

6) Private Provision

6.1 The Role of Private Provision

- There should be no support or any form of incentive for privately provided care, through tax allowances or any form of subsidy.

- There must be strong professional guidance about the circumstances when non NHS provided health care options should be offered and proper independent expert advice available to all care users on their rights and options (including, where appropriate, advocacy).

- The NHS may continue to be a provider of privately funded health care only where this can bring benefits to the NHS, but there must be proper guidance and transparency.

- All Trusts must report separately in their accounts the level of income and expenditure from private patient activity in a prescribed manner covering Joint Ventures and similar organisational devises. The calculation of expenditure on private patients must include a contribution for the NHS costs in training the staff involved and the finance costs of the equipment used. In addition, the “profit” derived from treating private patients must be greater than the “surplus” which would have arisen from treating NHS patients with similar conditions.

- Any plans by an NHS provider to significantly change the level of private patient activity must be consulted upon and supported by appropriate local authorities and the Governing Body.

- Healthcare must remain a predominantly publicly delivered service, and the public provision of social care should be strongly supported.

- All providers of care must comply with minimum standards around workforce terms and conditions, training, development and supervision as well as quality standards.

- Commissioners/planners should review all care services on a regular basis and include in that consideration proper engagement with service users and communities. Reviews should be published. Where they are satisfied that the service provided is appropriate they should support it (preferred provider).

- Any proposed change to care services should be examined also for its wider impact on other services – a whole system test.

- Where a service from the current provider cannot be improved to the required quality standard then competitive procurement including private providers may be used.

- Where a new service is required which is currently not provided NHS providers would be the preferred provider

- Commissioners must ensure that all providers of NHS care have public and patient involvement embedded in their governance.

- The national framework should require that no service may be procured using a contracting arrangement unless as a minimum:-

- the service is largely independent of other services

- the quality requirement can be properly specified in a legal contract and there is the expertise to manage such a contract

- there are already a number of recognised providers of such a service.

- The national procurement regime as permitted under EU Public Procurement Directive for care services should ensure that there is no compulsory competitive tendering.

- There should be a test of suitability applied to prospective private care providers applied through continuing registration conditions or through contracting. Major changes in capitation (for example) could enable contracts to be terminated.

- Where a public body has a legal contract with a private provider that contract must ensure full openness and transparency – with no “commercial confidentiality” outside the actual procurement process.

- Contracts and procurement requirements should specify steps to ensure continuity of care (which might include some financial bond being required) and knowledge of local conditions and services and populations would be an essential condition.

- All major PFIs should be transferred to PropCo or a similar national “toxic” asset management regime that should take over the major contract management issues and use its scale and expertise to ensure contract compliance.

- Contracts should be assessed against any opportunity for renegotiation or possible buy out, insofar as that has not already been done.

- Trusts should be charged a fair usage charge, as some variation of public dividend capital, using the same approach as has been adopted for a limited number of Trusts in difficulty.

- It is unlikely that public capital funding will be available on any scale and every effort should be directed at maximising the best use of existing public sector assets.

- There should be no further PFI or PF2 deals but variations on P21 will be permitted for smaller scale works (<£50m). There should be no further LIFT schemes.

- It is unclear how major capital schemes, say for a hospital rebuild could be financed. Many suggestions have been made – borrowing from capital markets, raising local loans, using pension funds, using public loan board and we should urgently develop a policy.

6.2 Private Medical Practice

6.3 Private Provision of NHS Funded Healthcare

- The national framework should require that contracts should have the following minimum characteristics:

- specify the number of FTE staff and the precise quality of staff specify tasks

- performance measures as a floor not a ceiling

- stiff penalties for breaches

- specify the service in detail and the way it is currently provided

- insist on local people and local continuity

6.5 PFI

6.6 Future Capital Funding

7) Mental Health

- There must be an end to stigma and discrimination in relation to any form of illness.

- Good mental health depends on parity of esteem, moving to a system of whole person care, eliminating the distorting effects of markets and local strategic planning led by clinical professionals. Funding should be protected rather than being seen as easy to cut.

- Mental health staff must not separate themselves from general health services and there must be a return to the easy clinical contact with all medical specialities. This requires the removal of the commercial barriers.

- Community and hospital mental health services need to be seamless, planning should follow medical evidence, clinical audit, multi professional equality and NICE.

- For primary prevention, consultants should be expected to respond to requests for education from schools, places of work, the Police and other institutions. For secondary and tertiary prevention we must develop sheltered work programmes funded partly by appropriate benefit; and the routine use of investigative measures in order to plan remediation, taking place in rehabilitation units.

- We should improve ward standards, continuity of care and the consequent efficiency of the management of serious mental illness. With calmer wards, a more therapeutic environment could be developed, based on clinical, psychological and educational evidence. Psychological treatments particularly should be strictly limited to diagnostically defined conditions, time limited and automated where appropriate.

- All new patients should be referred to the consultant and his team, diagnoses made, treatment plans drawn up and recorded in a clinical case register of the service.

- Longer -term and more severe patients should have care coordinators and the full care plans adhered to, with audit to ensure proper operation.

- The Royal College should reassert its domination over local clinical teaching and maintenance of clinical medical standards.

- There needs to be thorough monitoring of legal aspects of the service and patients need more free legal assistance than that granted for the Tribunals. There should be a national guideline on the relation between the Police and the mental health services.

- Psychiatric patients are among the poorest in the land. Benefits are essential to those who cannot work and should be dispensed, using a proven instrument, by a statutory authority and not a commercial company, to a patient assisted where necessary by an advocate.

- Prevention of mental illness includes building community cohesion through process such as community development

8) Health inequalities

- We should embed reducing inequality within Care Constitution and make it a core objective of the health system

- The NHS of itself does little to reduce inequality and adjusting funding to reflect inequality does not appear to work.

- But the inverse care law remains as true now as it did 20 years ago and this inequity in resource allocation must be addressed.

- We should support a much greater role for GPs and primary care working with communities as well as patients in order to identify underlying causes of poor health

- Investment in housing or other environmental factors will give a better return than many other more direct approaches.

- The NHS should use its uniquely respected positioning within society to exert influence over improving health

- We should set targets for reduction of inequality and publish progress

- Children and young people should be assigned the highest priority in any strategy

- We must ensure liaison across government so that we address the wider determinants of health e.g. unemployment and their impact on health, particularly in the most disadvantaged

- We must base actions upon best evidence and a focus on outcomes

- We must involve communities in their own decisions about health and health care through techniques such as community development.

- We have to deal with the cultural issues so we can encourage early diagnosis and prevention rather than later treatment

- We must maximise the use of mechanisms of health protection, legislation and regulation to improve health

9) Workforce issues

- We support commitment to Agenda for Change and the national agreement on terms and conditions.

- We should bring back the agreement that prevented two-tier workforce arrangements.

- We should look to establishing some form of concordat or contract terms for private providers to the NHS to accept obligations around TU recognition and staff engagement, comparable terms and conditions, disclosure of information, training and development.

- The social care workforce has to be dramatically upskilled, paid a living wage and put into structures where they get proper management, training and development. Zero hours contracts should be banned and visit planning using 10 or 15 minute slots also banned. The excellent Charter proposed by UNISON should be universally adopted.

- The case for minimum staffing levels, especially as regards nurses, but also levels recommended by Royal Colleges for clinical safety is supported. How this should translate into regulation or perhaps just to management and monitoring has yet to be resolved. There should however be clear guidance on staffing levels, especially of nurses, that is publicly available along with monitoring which is also publicly visible.

10) Dignity and older people

- All people with a terminal diagnosis or considered to be at risk of dying within the next 3 months will be allocated a case coordinator whose role will be to ensure that their care is delivered on a whole person basis with their wishes (or best interests where capacity is limited) paramount

- The care coordinator will have both responsibility and authority for ensuring this is happens wherever possible.

- The barriers to the rapid arrangement of the necessary in-home supports (e.g. adapted beds, pain relief, care staff, etc.) will be analysed and removed at a system level

Appendix A – Whole Person Care Definition

There is the start of a definition of what this means from the perspective of the recipient – you know what it is when you eexperience it. This is adapted from the work done by National Voices:-

- I know who is in charge of my care

- I am involved in all discussions and decisions about me

- My family and carer are also involved (so far as I want)

- I have agreed a care plan which covers all my needs

- I have one first point of contact and they know about me and my circumstances and help me access other services

- I can see my records, decide who else can see them and I can make corrections

- There are no big gaps between seeing people having tests and getting results

- I always know what the next steps in my care are to be

- I know that all those involved with my care talk to each other and work for me as a team

- I get information at the right time and I can understand it, sometimes with some help

- I am offered the chance to learn more and set goals to include in my plan

- My plan is reviewed with me regularly and I am involved as much as I choose to be.

The suggestion is that something like this is set out in the NHS Constitution.

The major changes required to get to this kind of state are in the areas of clinical training, medical records, new tools and methods. This has a cost implication and will take time.

Appendix B – Local Authorities Commissioning and Funding

At present funding flows to commissioners through formulae established by NHS England and to providers through payment by results or through block contracts. The amount to be spent in total on healthcare and public health is set by government then allocated by NHS England to various national streams then to CCGs. There is no democratic involvement of any kind in the decisions about allocating resources.

The alternative is that funding flows through LAs as does the funding for various other public sector services. This has advantages. First it brings in democracy ie the major decisions about funding and priorities are set by elected people. (But they have to ensure the comprehensive NHS is provided and meet all guidelines.) Second it allows LAs to make bigger decisions across the whole of the public services – so they may invest in measures which reduce future demand for healthcare. Third it should bring scale economies into commissioning.

Under this model funds are allocated to local authorities based on (weighted) population. The LA makes the strategic allocations then delegates to the CCG the actual commissioning.

For CCGs there is a separation between the clinically critical tasks such as pathway design – but in some cases this can follow a national template. They would also be involved in monitoring quality, agreeing standards, deciding on competing priorities and on how best to allocate scarce resources. But, as above, they have to ensure the comprehensive NHS is provided and entitlements to care are met.

This is like the BMA model for commissioning which leaves some commissioning functions like procurement, contract ,management, information processing in something like a shared service (to get economies of scale), where clinicians advised but did not manage or carry out all the processes.

Appendix C – Commissioning

First there does need to be some agreement about what planning/commissioning involves. For any efficient system there has to be some objective basis for service planning, priority setting, allocation of funds, performance management. This will be underpinned by good information. Patients and the public will increasingly become co-planners. Indeed, much of the priority setting and quality indices will set with local communities who will also see themselves as health creators..

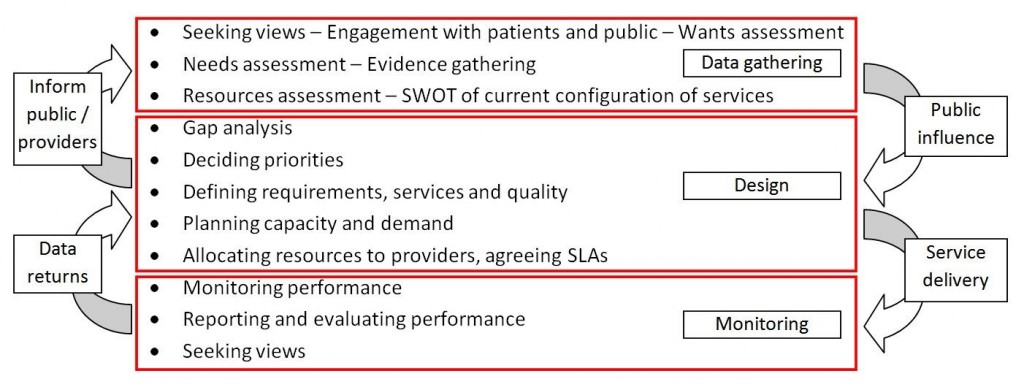

The conceptual cycle can be illustrated by:-

These functions would be necessary in any system, and so would have to be paid for.

[1] Commissioning as we use the word does not mean activity put in place to support a market, internal or external. In all state funded health systems there is commissioning of some kind as decisions have to be made about funding flows, priorities and quality. This can be achieved within a single organisation (as in Wales) but requires functional separation and open and transparent systems.

Appendix D – Local Health Watch (LHW) and Community Health Councils (CHCs)

The lessons from the Community Health Councils (good and bad) should be understood.

- The funding and management of CHCs was controlled at Regional level, insulating them from political pressure locally.

- Their operation was very publicly transparent – all meetings were held in public.

- They built up relations of trust with local staff and organisations, so benefited from a great deal of what would now be called whistleblowing. Staff would contact the CHC suggesting that they might like to visit a particular area of their hospital and telling them what they might like to look at. As the CHC visited regularly this was quite safe for the staff.

- The informal role taken by many CHCs in assisting complainants was helpful in alerting them to problem areas that needed investigation.

- CHCs were stable organisations, with experienced staff who built up relationships of trust over long periods. Since they were abolished the successor organisations have been transitory with short term funding and repeatedly reorganised.

- This suggests that LHW must be adequately resourced, independent and of sufficient credibility that there can be good quality staff. If a LHW has serious concerns it should be able to access support and assistance from specialists and experts at the national level. LHW should provide a channel for confidential advice and support for “whistle-blowers”. The controlling bodies of LHW should always have representatives from the third sector and from local workforce.

- There remains an issue about how LHW can be seen to be accountable?

This suggests that LHW must be adequately resourced, independent and of sufficient credibility that there can be good quality staff. If a LHW has serious concerns it should be able to access support and assistance from specialists and experts at the national level. LHW should provide a channel for confidential advice and support for “whistle-blowers”. The controlling bodies of LHW should always have representatives from the third sector and from local workforce.

There remains an issue about how LHW can be seen to be accountable?