First published in One Nation: Power, Hope, Community, edited by Owen Smith and Rachel Reeves , One Nation Register 2013

Last year, Ed Miliband’s conference speech galvanised the party and began reshaping the political consensus. With that single, striking phrase, ‘One Nation’, he was able to offer a critique of the existing social order under the Tories, whilst simultaneously offering the hope of a better one under Labour. Its great achievement was to be both radical and conservative: it provided an alternative political economy that spoke to contemporary concerns over the economic crisis, living standards and the nature of change, without retreating into nostalgia.

Yet to grasp the full nature of Ed’s argument we need to situate that speech within the context of three important prior interventions. These form the basis of the political architecture that defines our One Nation programme and provides the contours for a new approach to policy development.

First, there is the concept of the ‘Squeezed Middle’, which articulates the problem that will define the next election: how to arrest the decline in living standards for low and middle earners. This cost of living crisis has become more acute under David Cameron, but median wages for this group were flat as early as 2003, a trend that continued throughout the recession and beyond: even as the economy flirts with a return to growth there appears to be no sign that real wages are set to improve.

Second, there is Ed Miliband’s persistent and determined call for a more ‘Responsible Capitalism’. This provides our aspiration and our destination; and a vision of the fairer, more equal society we wish to build.

Finally, there is the idea of ‘predistribution’, which outlines the Labour Party’s new political methodology -our process of moving from Squeezed Middle to Responsible Capitalism.

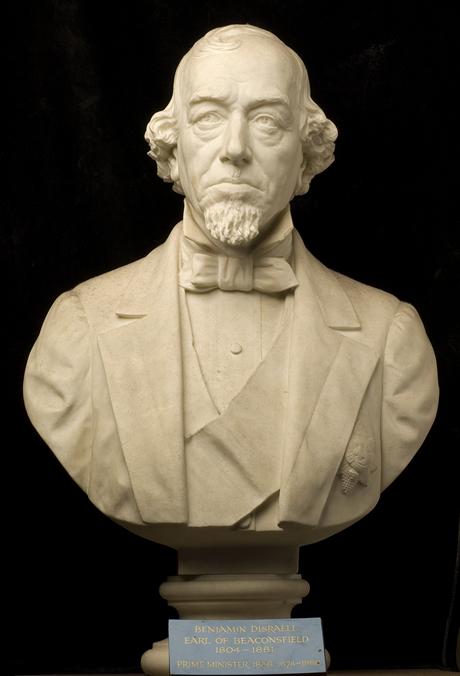

However, as any historian will tell you, ‘One Nation’ is far from a new phrase. Stolen – as Ed was the first to acknowledge – from Benjamin Disraeli, arguably the Conservative Party’s most celebrated champion of the aspirant class, this is an idea with a clear and defined political lineage. To fully appreciate the ways in which it speaks to the condition of Britain today (and indeed, to the condition of the Labour Party), it is helpful to start with a look at the historical antecedents and ideological currents that helped to shape Ed Miliband’s ‘One Nation’ politics.

Catching the Tories bathing

Disraeli first articulated his ‘One Nation’ philosophy not, as is sometimes thought, during his infamous, brandy-soaked marathon speech at Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1872. Rather, it was when, as an out of favour young politician and jobbing author, he published his 1845 manifesto-cum-novel Sybil or the Two Nations. By then Disraeli was the de facto leader of the fledging Tory ‘Young England’ movement, which argued for a return to the social conservatism and paternalistic duty of pre-industrial England. Sybil, then, was deliberately intended as a distillation of his and their political philosophy.

In the novel Disraeli lambasts the greed and division of the great nineteenth century industrial cities -Manchester, Birmingham and the first industrial city of them all, Stoke-on-Trent. There could now exist within one city, he protested, two entirely different nations, ‘between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets’.

These two nations were ‘formed by different breeding’, fed by different food, and governed by different laws. They were ‘the Rich and the Poor’.

Of course Disraeli’s indictment was far from a lone voice of criticism. From Gaskell to Dickens, Ruskin to Marx, the poverty, division and rampant inequality of the industrialising cities featured in the work of many mid-nineteenth-century writers. So, as we approach what often can feel like Victorian levels of inequity today, it is quite natural that we look to this era for political inspiration.

But the question remains why One Nation? Why, given the intellectual riches on offer, should Ed Miliband choose, as Disraeli himself might have put it, to catch the Tories bathing and walk away with their clothes?

The reason is that, on so many levels, it is Disraeli’s analysis that best chimes with our own – not least in his response to Queen Victoria’s 1851 gracious address, when he famously said “This too I know. That England does not love coalitions.”

Indeed, a proper understanding of Disraeli shows that in certain extreme epochs it is possible to be both conservative and radical. We are currently enduring one such era.

Challenging the consensus

Despite signs that we may be finally clambering out of recession, we remain in the eye of a volatile and unpredictable economic storm, brought about by excessive faith in the economic orthodoxies of neoliberalism. And what makes Disraeli so interesting is that he, like Ed Miliband, was motivated by a healthy disrespect for the political and economic orthodoxy of the day.

In both Sybil and his earlier novel Coningsby, the target of his ire was the laissez-faire, night-watchman state propagated by the ‘Manchester School’ of liberal conservatives. Rather than the barren exchange of the cash-nexus, Disraeli stressed the ties that bind; he believed in a moral conception of society beyond the narrow confines of the marketplace.

This attitude is typified by Stephen Morley, the radical agitator in Sybil, who roundly condemns the ‘great cities’ where ‘men are brought together by the desire of gain’. Such men ‘are not in a state of co-operation, but of isolation, as to making of fortunes; and for all the rest they are careless of neighbours’.

This division into ‘two nations’, and the ruinous condition of the urban poor of industrial England, was the social cost of this exclusive focus on economic gain. But, as Disraeli saw, such excessive desire was symptomatic of an entire model of capitalism that was failing.

Clearly, Ed Miliband has no interest in replacing the neoliberal consensus with the ‘Young England’ attempt to restore the lost order of pre-reformation England. However, he does share this one crucial insight with Disraeli. And what is more, this is one of the fundamental lessons we must learn from our recent experience of government: that there is only so much you can do to improve the conditions of working people without also changing the underlying structure of the economic model itself.

Beyond the bottom line

The aesthete and socialist John Ruskin, one of Disraeli’s most brilliant contemporaries, offers a further insight from the Victorian era that remains relevant to today’s political context – and it is one that Disraeli would have shared: not everything of value is reducible to price, or measurable in pounds and pence.

As Ruskin wrote in his 1860 essay ‘Unto this Last‘:

It is impossible to conclude, of any given mass of acquired wealth, merely by the fact of its existence whether it signifies good or evil to the nation in the midst of which it exists. Its real value depends on the moral sign attached to it, just as strictly as that of a mathematical quantity depend on the algebraic sign attached to it. Any given accumulation of commercial wealth may be indicative, on the one hand, of faithful industries, progressive energies, and productive ingenuities: or, on the other it may be indicative of mortal luxury, merciless tyranny, ruinous chicanery.

This was a critique with which Disraeli – with his distaste for the Manchester School – would have undoubtedly concurred. But even now it has lost none of its force. Because today, the pace of change wrought by globalisation has created a sense of loss and of dislocation amongst many of our communities.

However, the last Labour government sometimes failed to respond to this anguish in anything other than the most urgent economic terms; sometimes we appeared to belittle the concerns of those who were fearful of the pace of change, or who longed for stability and order. As Jon Cruddas has suggested, the government sometimes offered fuel for the caricature that it was collapsing the entire Labour project into an exercise in fiscal transfers.

And as a result of this focus, perhaps it also contracted what R.H. Tawney, writing in his 1931 masterpiece Equality, called “the lues Anglicana, the hereditary disease of the English nation’ – a ‘reverence for riches’ that disregarded the socialist ethic of fellowship.

We must learn from all this, from Tawney, Ruskin and Disraeli, and avoid the pitfalls of ‘monetary transfer social justice’, which doesn’t do enough to challenge existing structures and concentrations of power. The materialist Coalition, of course, is utterly incapable of learning such lessons, as it eagerly sets about privatising every public good for which they can find a buyer.

A recovery made by the many

There is a further important way in which the ‘One Nation’ idea is both conservative and radical. When Ed Miliband gave his speech in Manchester he also offered a clear and renewed commitment to the party’s historic crusade of lifting the life chances of working people. On this he was absolutely unequivocal: inequality matters. Too great a distance between the two nations harms social cohesion and undermines our sense of solidarity, ultimately impoverishing us all. That is all the more the case in an age of gross inequality between the very richest and everybody else.

Anthony Crosland’s influential 1956 work The Future of Socialism grounded the concerns of democratic socialism primarily in equality – as opposed to public ownership – and since then it has been common to label the dominant strand of Labour political economy as ‘Croslandite’. The Croslandite model asserted that the best way of advancing social justice was through accepting a relatively untrammelled version of free market capitalism, and to then fight injustice by redistributing the proceeds of its ‘perpetual growth’.

But this model is surely inadequate to addressing our problems in 2015. In particular it lacks a critical stance on the way in which the market concentrates existing distributions of power and inequality. And it prevented us from distinguishing between different types of capitalism and growth, leaving us unable to make the kind of economic value judgements demanded by our One Nation politics.

It is particularly important that we are explicit about growth. A return to the kind of growth that is disconnected from rising living standards will no longer suffice.

Any lingering pretence of commitment to the kind of growth we need to see was finally abandoned by George Osborne in the 2013 budget. After failing repeatedly to deliver on promises to revive business investment, he discarded his export-led ‘march of the makers’ rhetoric and made the centrepiece of his budget a ‘Help to Buy’ scheme that the Office for Budget Responsibility say will push up house prices, while doing little to increase the house building we so urgently need. There are growing signs that the much delayed recovery is mainly benefiting those at the top, while most families are seeing real wages and incomes continue to fall.

We need growth that reduces inequality, delivers more secure work, is more environmentally sustainable, and above all benefits the regions outside of London and the South East. And this approach not driven solely by a concern for social fairness: Ed Miliband’s One Nation economy will enable us to succeed as a country, and create a recovery which is made by the many and – this time – built to last.

An economy that works for working people

Widening the discussion about of what kind of growth we need points to further ways in which our old political economy is lacking: it is unable to offer answers to the basic questions that Ed Miliband has placed at the heart of Labour Party policy in these tough times: how can we make a difference in a restricted economic climate, how can we change society?

These questions perhaps make the last idea in the One Nation trilogy – predistribution – the most important one for us to grasp.

Any political party that fails to answer this question is not fit to form a government. Indeed, such is the scale of the economic challenge we face in the next ten to twenty years, that I do not think it is an exaggeration to describe the need to answer this question as an existential challenge – for all political parties.

In this context, a closer look at the tax and benefit system begins to reveal some of the the fundamental flaws in our old political economy. Although our current society is scarred by inequality, this is certainly not because of insufficient concern on this issue in the New Labour years. Far from it. Indeed, as OECD statistics show, New Labour’s legacy is a tax and benefit system that redistributes almost as much as the famously egalitarian social democracies of Scandinavia.

In fact, the reason that the UK still has the seventh highest levels of income equality of the 34 OECD countries is that it begins from the fourth most unequal starting point. Its levels of redistribution cannot overcome its predistribution – the way the market distributes its rewards in the first place. Put bluntly, we redistribute more but the underlying structure of our economy is more unequal and unfair.

A further problem with strategies that rely too heavily on redistribution is that they often fail to recognise that resources are useless if people don’t have the power to use them. To put the argument at its simplest, there is no point in increasing people’s entitlements if they feel marginalised by a society that they no longer recognise or feel part of, or if they lack the capability to access basic services. The Labour mission should also focus on strengthening these communities and demonstrating that society works best when people work together and share in each other’s fate.

Of course Labour can be proud of our redistributive legacy, and the fact that our tax credits helped to take a million children out of poverty. And redistribution will obviously remain part of the Labour way of delivering fairness. But we need look beyond that to predistribution.

Our opponents have poured scorn on this idea. But Britain needs new ideas. And one of the great assets of Ed Miliband’s leadership has been his ability to develop new ways of thinking, new ways of approaching the many challenges we face. We need to find ways of ensuring that economic power and the proceeds of growth are more evenly spread throughout the economy before redistribution – to reform the underlying structure of the economy rather than limiting ourselves to ameliorating its inherent inequality.

This is a significant challenge to the traditional political methodology of social democracy. A predistributive approach gives primacy to reform. Out go flashy new ways of spending money and in come smart, inexpensive interventions that have the power to reshape the existing rules of the market.

The challenge of rebalancing the economy and spreading wealth more evenly in these tough times is an extremely difficult one. But it will be made that much easier if we can offer an authentic story of national renewal, one that is desperately needed at a time of fragmenting identities, political apathy and the increasing drift to a two-nation Britain

But the Labour Party’s own renewal is already underway in the policy priorities that Ed Miliband has set out, and the shadow cabinet is working together to develop. And the predistribution agenda is beginning to open up pathways to a One Nation Britain.

In the past year we have set out plans for our gold-standard Technical Baccalaureate, which provides a rigorous vocational pathway for the ‘forgotten 50%’ who do not wish to pursue the academic route; and for the British Investment Bank, alongside a network of regional banks based on the German model, that will provide finance to SMEs in capital starved regions of the country; and for an amplified campaign to encourage large employers to sign up to the Living Wage.

Perhaps the best example of our plans in this area, however, is our approach to social security and housing. We must be prepared to shift the focus of social security spending from benefits to bricks and mortar – to building houses, not lining the pockets of rentier landlords.

Other proposals to help us find new ways of holding unchecked corporate power to account include putting employees on remuneration committees, and the compulsory publishing of executive pay and corporate tax arrangements, as well as the number of employees that are paid less than the living wage.

In addition, Ed Balls and Chuka Umunna have commissioned Sir George Cox to produce a report on overcoming the corrosive short-termism in British business, and the tendency to suck away investment at crucial points in the growth cycle. And as part of Stephen Twigg and Chuka Umunna’s initiative for a One Nation Skills Taskforce, Chris Husbands has highlighted how we might build a more highly skilled workforce, in order to compete in a globalised world on our own terms – as opposed to participating in the ludicrous Conservative pursuit of a low-wage, low skill race to the bottom.

The forward march of labour restarted

We have begun the forward march to One Nation Britain – a country in which prosperity is more fairly shared, and we all work together, backed by preserved and renewed institutions. Although this is a hard task, there are grounds for qualified optimism. That is because many of the answers to the challenges of our current political context – globalisation, fiscally responsible change, the rejuvenation of our political culture – can be found within the uniquely Labour contribution to social democracy.

The answer lies in the movement itself: for in becoming too reliant on the state as the only means of mitigating market outcomes, we have neglected our associationalist heritage as a movement of democratic grassroots activists: our history of co-operatives, mutual societies and trade unions. It is by rediscovering this heritage that we can begin to put ‘the future in our bones’, as Eric Hobsbawm once memorably put it (after C.P. Snow).

So, whilst we are deeply indebted to Benjamin Disraeli for the lucidity of his analysis, and can find a common cause with his dream of a Britain united, the energy to realise our One Nation vision, and transform our communities from the bottom-up, is all our own.

Tristram Hunt is MP for Stoke-on-Trent Central and a shadow education minister.