The Bulletin of the Pioneer Health Centre, Peckham

Vol 3 no 5 September 1949

This month, Robert Furneaux Jordan, F.R.I.B.A., has kindly undertaken to write our editorial column. Readers will know him as Principal of the A.A. School of Architecture, and as an architect, lecturer, broadcaster and writer of international repute.

Architecture is, in its most elemental form, the enclosure of a space for an activity. An Eskimo, enclosing space for living, has to consider:

- the activities of his family,

- the best shape for this,

- the best available material,

- how the material should be put together to produce the shape,

- the best site,

- a neat appearance.

This is architecture. The result is an igloo on the thickest bit of ice to hand.

The important thing is that for the Eskimo this process of thought was not conscious. It was not a summation of six separate ideas; it was a synthesis based on racial tradition, something as nearly biological as the hive or the nest.

The contemporary problem is more complex, but the solution must be as directly biological in its essence. Rapid social and industrial changes —the tempo increasing all through the centuries and rising to a climax in the 19th and 20th centuries—have produced not only confusion but complex living patterns alien to man’s biological nature. For us the igloo would be uncomfortable, for the Eskimo it is good because in the most intimate biological manner it is part of him.

If the architect is to provide the complex spaces needed for contemporary activities, without committing a biological crime against the nature of man, then he must—with the biologist—understand the complex creature for whom he builds. This is the first step towards planning a rhythmic and living pattern for a healthy humanity. It is in itself a vital step towards a healthier humanity. This responsibility the architect must now accept, in accepting it he may again become a key figure in civilisation—a position he lost in the Reformation when building became the luxury art of an aristocracy.

The architect’s opportunities are unparalleled. Industry has given him new and wonderful materials: steel, aluminium alloys, plastics, cements, rubber and resinous glues. Factory techniques have given him the most exciting tool the craftsman has ever had.

In this new architectural context the building of the Pioneer Health Centre has a significant place. Against a background of warped complexities in the contemporary pattern of living a biologist conceived a new activity and research—the experimental cultivation and study of health. He conceived the idea of what is now ‘Peckham’ and set about translating it into reality. In so doing the most advanced techniques of the time were used. It was a synthesis of the new idea with the new architecture.

If the architect is to understand modern man, the biological organism for whom he must build, then he must understand him biologically. Thus ‘Peckham’ is not merely interesting as a building; research done at ‘Peckham’ can make a vital contribution to architecture. It can give the architect much of his data. But ‘Peckham’ has done more; it has underlined the too often forgotten truism that architecture without people is meaningless.

The Birth of a Building

In order to describe Peckham as a building we must first recall the purpose for which it was built. Primarily a laboratory for the study of health, the building has the no less important function of cradling the growth of health.

The study of health implies observation without interference. The awareness of this fact arose naturally from the scientific integrity of the biologists. From their faith in the innate order of living processes arose the conviction (tested by a long process of experimental research) that health or wholeness implies autonomy, and a free environment. These two requirements, observation without interference arid a free environment to foster health are seen to be one and the same thing when expressed in concrete form. This is not really surprising since ‘Science is what you know and Art is what you do’ (Lethaby). The very fact that the biologists were people implied that their scientific and human approaches would tend towards similar requirements for their building.

Dr. Scott Williamson, in looking around for an architect discovered that, because the requirements of the building he needed were so different from anything that had occurred before, it was difficult to find an architect who could interpret them as economically as he wished. He himself had already begun to visualise his needs in terms of space and form so he decided that he and Sir E. Owen Williams, a very imaginative structural engineer, should design the building together. Thus the architect and the client were identified, which proved in this case to be a successful arrangement.

One of the main points they had to consider was flexibility. Movement must not be impeded, because movement is an essential part of the dance of life, and to restrain it is to restrain life. Free circulation and visibility, and the flow of space into space are all necessary qualities of the building. Flexibility could also be achieved by the design of space for multiple use, and the design of furniture which could be easily moved and handled, by those who were to use the building.

There is a sense in which a building can dictate activity just as forcibly as people. This may be done in a direct way by its shape and equipment. It can also be effected by the mood which it induces. For instance, if the Centre had been decorated in the manner of the Roman Baths of Caracalla, one can imagine that the activities of people within it would have been very different! In fact it was given a neutral atmosphere by using natural materials and quiet colours, so that it is suitable for all purposes. Such a neutral background sets off rather than competes with the rhythmic pattern of human activity. On festive occasions, the people spontaneously devise decorations which transform this atmosphere into something positive and appropriate. One thing that the atmosphere decidedly is not, however, is domestic, and it is interesting to observe that in the one place where a note of domesticity was introduced, a pair of cosy fireplace nooks, it completely failed to find the approval of use. Now they are only deserted reminders of the fact that although the Centre is an extension of the home (or family environment), it in no way acts as a substitute for the hearth itself. Another reason for avoiding any particular atmosphere, particularly the domestic, is that it would have encouraged a set pattern of behaviour in new-comers to the Centre. Its unusual character is of value in provoking a new and individual response from them. .The pilot experiment gave an idea of what the Centre would have to provide for in the first place. This was, briefly, to incorporate in one building facilities for all the diverse activities which members of families were participating in, as individuals, in the outside world. The really remarkable thing about the Centre is the completeness with which it made its jump from the old conception of a social club, with a programme of set activities, to a family club in which free development could take place. This means that there was a qualitative difference of attitude towards the new building, and towards its equipment.

The designer and the engineer saw the need to apply the most advanced building techniques to solve what was then a unique architectural problem. Research into particular aspects of the technical problem was conducted in many countries, and included such things as a study of heating and ventilation in Switzerland and the use of high-tensile reinforcement in Holland.

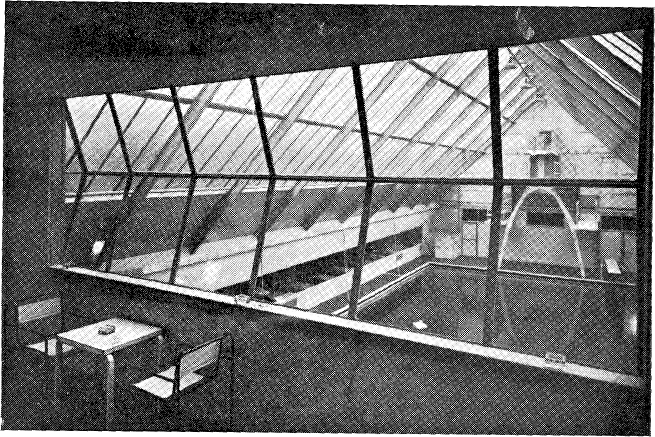

The basic structure of the building consists of three slabs of continuous reinforced concrete, surrounding a central swimming bath, and supported one above the other by columns. Each component of the structure merges into its neighbour and the whole weight of the building is distributed from the roof to the foundations in a continuous and unified way. Thus, it was possible, by precise mathematical calculation, to design a fairy palace of extreme delicacy, with columns as thin as one’s arm and floor slabs little thicker. This more daringly direct answer to a specific structural problem had to be modified because of building regulations, but the actual building is based on these proposals. With this structure there was no need for solid load-bearing walls, so that unimpeded circulation became immediately possible, and sunlight could penetrate the surrounding glass walls, which keep out the wind and the rain. Surprisingly enough, this liberal use of glass has not been uneconomical with heating. When one’s clothes are soaked through on a windy day, the body loses a large amount of heat by evaporation. Most building-materials absorb a great deal of moisture, and thus lose heat in a similar way, whereas glass is one of the few that sheds water readily. Furthermore, the rays of the sun can enter through glass freely, but, once the heat has been absorbed, it cannot be lost again by re-radiation. The definition of activity spaces within the building is achieved by means of light partitions, some made of brise blocks, others of wood and glass, which can easily be removed and changed if necessary. The success of the experiment depends on the ease with which a person can change his activity from one thing to another, and this in turn implies the easy control of his environment—both its space and mood. A standard ceiling height was adopted throughout most of the building so that it would be possible at a later date to develop a system of light adjustable screening which would give hour to hour adaptability of space and mood. This standard ceiling height is no more than eight feet nine inches, but rather surprisingly it does not have the oppressive effect that some people expected, and the relatively low ceiling gives a feeling of ‘cosiness’ and intimacy. Probably this is due to the generous natural lighting and the special effect of the columns.

The courtyard flows under part of the building, and this partly enclosed section, which is sheltered from violent air changes by an overhead screen at its edge, is usable even in winter, for radiant heat panels directly warm the children who play there. The courtyard itself was purposely left unlevelled when it was tarmacadamed, for nothing is gained by smoothing out hazards for children who are always looking for fresh ways of developing their skill in negotiating difficulties.

Necessity Mothers Invention

A fresh approach marks every detail of the building’s construction. Solutions that are simple, economical and functional abound, of which the gymnasium and theatre floors are outstanding examples. Resilience was required in both cases (for the theatre was designed to be used for badminton and dancing too), and was obtained by using laboratory gastubing stretched between the cork tiles. In between the tubes cork chips were poured, coarse for the gymnasium and fine for the theatre, in order that the former should have plenty of spring and the latter slightly less. This method of obtaining resilience in a gymnasium floor has since been used, to our specification, at a well known public school.

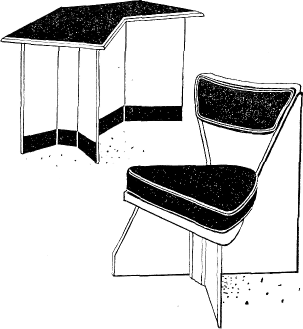

- The table illustrated was designed (by Christopher Nicholson) for intimate groupings, to hold at least six cups or tumblers and is so shaped that, when placed together, the tables form a sociable unit for larger parties.

- Also designed to combine comfort and sociability with hard wear and low cost. The structural parts of six chairs are cut from one standard size sheet of plywood with no wastage.

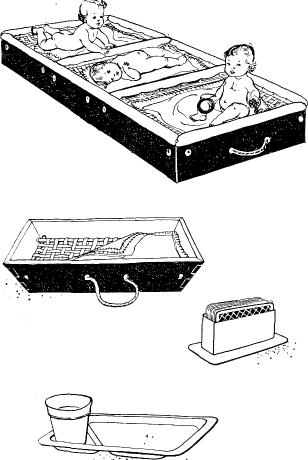

- The ‘conversation piece’ designed by Doctor Pearse (even at this early age the companionship of one’s neighbours is a stimulus).

- Also designed by Doctor Pearse, stackable infant’s cot. Notice the simple open webbing which takes the place of a mattress and which can be taken out and scrubbed.

- We think the advantages of the ‘plate-saucer here illustrated speak for themselves. As for the card-holder, other clubs may have them too, but we could find nothing suitable for the purpose, so this card-holder is made for us by a centre-member who is a metal worker

This fresh approach is seen particularly well in the Centre’s furniture. The equipment of the Centre must be regarded as part of its architecture, for it is quite as important a part of the free environment as the space itself. Before the war, there was an enormous range of equipment for activities of every sort, yet just as the spaces provoke flexibility of use, so the ingenuity is stimulated by avoiding over-specialised and foolproof equipment. Peckham’ does not aim to produce specialists, but to give the opportunity for the development of specificity in all fields. The succeeding age groups are unconsciously guided and enriched by their contact with people more developed than themselves, so that there is a sort of mutual aid in the use of equipment and space.

Space in action

When the Centre was first opened, hysteria was the immediate reaction of all the children who joined. When ordinary lives are bounded by the crowded home, the schoolroom, the office, the ‘bus, the shop, cinema and public house, none of which have any real space that can be freely used and enjoyed, there is a real need for space itself. Once the excitement of living in such spaces as ‘Peckham’ provided had spent itself, the activity pattern took on a natural order.

The aesthetic effect of the building in use, with its people and its furniture is a powerful one. The work of Alexander Calder an artist-sculptor who uses natural forces to build up moving, swinging, balanced systems of independent constituent parts affords a mechanistic parallel to the artistic effect of the biological pattern of people and environment at the Centre. The important thing is that this pattern is not sought after but found. (‘Je ne cherche pas, je trouve’—Picasso).

The Open Door

In the Centre no rooms have locked doors. Except when something as private as a ‘health overhaul’ is taking place there are few closed doors either. You can see across and along the building (encompassing all that is going on within it) and through its glass walls to the pleasant greenness of the trees that surround it.

In this building life circulates as freely as the air itself. Where there are no closed doors anyone may venture. With no embarrassing threshholds to cross, there will be no exclusive groups and no intimidating hierarchies. Snobbery will not take root.

Members of a newly-joined family find themselves surrounded with a wealth of visible opportunities. It is this visibility which—if they still have any capacity to grow—will sooner or later draw them into the swimming pool, or on to the theatre stage, or behind a fencing mask, or lead them to make headway in some other surprising way. (‘ Look at Mrs. So. and So,’ says mother, ‘forty if she’s a day. If she can swim, why not me.’)

This much the visitor can see the first time he spends a few hours in the building. From here it is not a very big jump to a startling picture of what must be going on, or rather, not going on, outside the Centre.

In Camberwell, as in the Centre, there are swimming pools, dramatic groups, discussion groups and the like. Though they are well-attended, it is clear that the bulk of the people cannot be using them. This comes out in the Centre’s observation of its own new member-families. Repeatedly it happens that a family joins the Centre because one, and only one, of its members is persistently clear about how he wants to spend his leisure time. The rest of the family are ‘dragged’ there because, the Centre being a family club, he cannot join without them. ‘We’re busy people, Doctor, we shan’t have time to come round much. It’s for the boy’s sake we’re joining.’

So far as spare-time goes, time soon proves that they are anything but busy people. They have, too often, no idea how to spend leisure, no friends with whom to spend it, and no developed or developing capacity by which to spend it. Watching so many of them getting ‘drawn into things,’ largely because those things can be seen, the visitor begins to understand at least one of the reasons why more people do not make use of the Borough’s facilities.

Some of us come to understand Peckham’ through our hearts, others through our heads, some of us through what has been lacking in our own lives, and some through a specialised field of study. There are all sorts of ways of coming at it— but architecture is perhaps one of the easiest, because architecture is something you can see and because it is so logical.

In the post-natal consulting rooms, for example, a visitor, in between consultations, may sometimes sit where the Doctor sits. Looking into the adjacent nursery he may watch for himself an over-protective mother taking courage to leave her baby with all the other babies. Commonsense shows him that it is the position of the nursery (into which the mother goes to dress her baby after the consultation) which facilitates this first stage of ‘skirt weaning.’ Later in his tour he may see that same mother with her friends in the swimming pool. Meanwhile, he will be noticing that companionship takes place amongst infants much earlier than is commonly supposed. So the meaning of the dual adventure, enjoyed on common ground, the baby exploring life with his friends, the mother with hers, will come home to him. In the nursery too he will watch the infant using the first simple equipment that will lead it so smoothly on to the use of more complex equipment in the toddlers nursery, thence to the babies’ swimming pool, to the rope ladders and climbing frames in the gym, and to the roller skates, bicycles, and scooters, out on the playground. This begins to explain how it is that the Centre mother can become, neither fearful nor foolhardy, but as intrepid for her child as is the child itself. The visitor is now to some extent ‘behind the biologists’ eyes,’ able to assess a little of what they see in their constant study of the child, and to understand that it is the visibility in the building that makes this study possible.

In the last chapter of ‘The Peckham Experiment’ there is a sentence which reads ‘. . . no list of the various separate ways in which the Centre meets the needs of the family will reveal its full significance for that family.’ Here lies the difficulty of understanding ‘Peckham,’ but once the student of ‘Peckham’ is within the Centre that difficulty disappears, for the building is so designed that the pattern of life the people are weaving together is there to be seen.

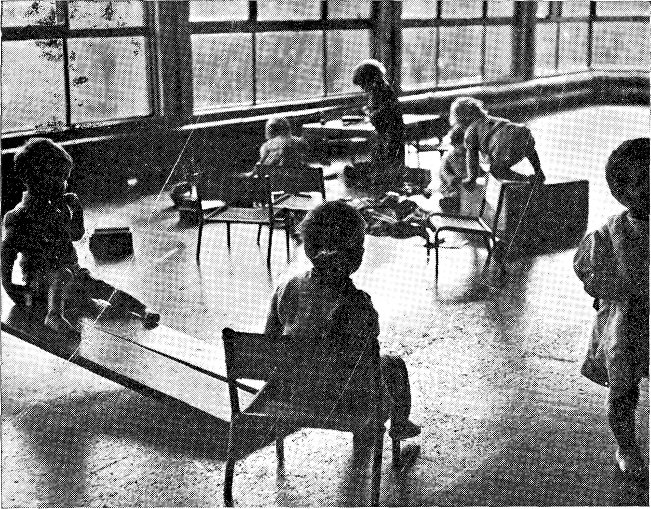

In a bay of the long room for instance in the afternoons, the children of the Centre’s own school, and indeed any other Centre child of between 3 and 8 years of age, may be seen quietly absorbed in indoor pursuits (reading, painting, modelling, brick-building, etc.). In the opposite bay a group of mothers may be dressmaking, and some mothers will be with their friends in the cafeteria, on the far side of the pool. The child, though it is not round her knees to distract her, is within sight of the mother. Though she is aware of what he is doing, her attention is not focussed upon him. He and she are in fact upon common ground, and when one begins to think about that ‘common ground,” and all its implications, one seems to see beyond the Centre to the home itself. ‘I used to be rather thankful when meal times were over,’ one mother said, ‘we’d so little to talk about. But now, we’ve so much in common, meal times are always a buzz.’

Once the village green was common ground. There the children played, sweet-hearting started between the young couples, the parents met and gossiped, and whole families grew to know each other well. The homes of the aristocracy were common ground too. People lived in each other’s homes, for the homes were spacious, generous and sufficiently varied to provide that common meeting place which people need if they are to enjoy themselves, and if civilisation is to nourish. But in urban life, today, there is no common meeting ground, unless you are so to describe the fish queue and the grocer’s shop. Cricket clubs, youth clubs, and so forth there are, and an invaluable purpose they serve, but these are created, subsequent to need, for a purpose, and the ground is not common to the family.

Outside the Centre, life is not unlike those familiar institutions in which corridors of closed doors challenge the intruder to enter. What, when you come to think of it, is Father’s club (excellent institution though it is) but a place closed by a door which mother may not enter? What father ever dares or wants to cross the feminine thresholds behind which mother may spend her afternoons? How many parents know how to unlock the doors behind which their children spend their school days?

NEEDS How the Building might grow and change

The Centre was planned so that it might change and be expanded in response to developing needs. There were certain unknown factors, and therefore certain sections—the spaces for the periodic overhaul of the family, for the nurseries and for the cafeteria—which were sketched in tentatively with the intention of revising and expanding them when experience had thrown further light on what was needed. Shortage of funds has hitherto made this revision impossible, but it is now possible to say what is required.

Birth of the child: Amongst the most vital and significant parts of the process of family growth is the delivery of the baby. The ideal place for the baby to be born is in the intimacy of the home, but unfortunately the inflexibility and inadequate facilities of the majority of houses makes this practically impossible. From the biologists’ point of view the departure of the mother to the maternity home represents a serious break in the continuity of observation, but still more a rupture in the family life involving separation of husband and wife, and the bringing of the new born into unfamiliar circumstances which frequently involve its exposure to the infections of the other inmates of the hospital. Mothers who have enjoyed their pregnancy in the Centre, almost without exception would welcome a specially equipped block where they could bring their babies into the world in surroundings already familiar to them, and under the care of doctors who were their friends, and from which they could return to their houses at an early date, there claiming the care and attention of the Centre’s midwives.

The first few months: In describing family integration, we referred to the way in which the close proximity of the infant nursery and the infant consulting rooms meets the needs of mother and baby at this stage, as well as allowing for the type of observation—particularly of the actions and behaviour of mother and baby—which the biologist seeks. At the moment this close proximity, of which experience has shown the value, can only be achieved at the expense of open air for the babies, since to be next to the examination department the nursery has to be wholly indoors. A solution to this problem—a partly open-air nursery—must come when the examination department as a whole is designed in its permanent form.

The first few years: When the children begin to reach the stage of walking confidently, they must be able to run in and out of doors freely, from comparative shelter to the open air. A semi-circular arcade, enclosing the open playground, has already been designed as an answer to this need. The arcade would also provide the main entrance to the building. The sheltered open space would provide for many purposes— e.g., for the needs of the school; and for children’s activities in general, as well as for dramatic performances and open air dancing in summer

Refreshments: At the moment, the cafeteria is a well-defined area attracting many people. The space itself, however, is rather limited and inflexible. A trolley service would be better able to cope with the Centre’s varying demands, making it possible for refreshments to be provided in any part of the building and the rhythmic pattern of activity to flow yet more freely—for instance when mothers wish to have tea in the sunshine or when a visiting polo team have just finished their match.

Separation of activities without exclusiveness: As was expected, the sight of action has been an invitation to action; action has thus proved ‘infectious.’ There are, however, certain activities inevitably require a degree of privacy, largely because of problems of sound—e.g., it is not easy to hold a meeting near where table tennis is going on, or a piano played. A system of light adjustable sound-proof screening that would enable conversing friends to become a discussion group and just as easily merge again into a larger whole, would allow for greater flexibility in the use of the building. Such screens have been designed but their construction is held up for want of money. The cost of having anything specially constructed at the present time is exorbitant. But once produced, we do not doubt that such screens would prove of value not only to the Centre but in many other situations, e.g., schools, community centres, even in industry, as indeed has been our experience with other specially designed Centre equipment.

Dancing and Building

Written by two architectural students who visited the Centre

‘Dancing and building are the two basic and essential Arts.’ So wrote Havelock Ellis in his book ‘The Dance of Life.’ The dance of birds in their courtship; their rhythmic movements as they build their nests—these things are readily apparent to us. Though less evident in human beings these basic arts are none the less real. To us this building of the nest is the well-spring of what is called architecture; and the making of buildings for community use is only an extension of this activity of fashioning the physical environment for specific human purposes. It is one of the tragedies of modern civilisation that the place where men and women bring up their families is no longer the product of their own hands, nor for that matter are the designs for their houses the result of any real investigation into their personal needs. The nadir of this process of disassociation of man from the house in which he and his family live is, represented by the suburban villa of the speculative builder. He is offered no say in the designing of the house and the workmen who build it are unknown to him. Against this lamentable background we have to build anew. The technical possibilities of creating houses worthy of the sacred human functions for which they provide shelter are at hand though we may have to look for them in the aircraft factory or the shipbuilder’s yard. The Centre at Peckham is only one example of what could be achieved more than a decade ago by the application of advanced techniques to building. To-day the possibilities are even greater and not a few of the younger generation of architects have visualised and are working towards, the possibility of providing houses which can readily be assembled and changed to suit the needs of a growing, changing family. Extruded aluminium sections will be the structural twigs of the human nest and sheets of glass and hollow plastics will be the feathers that keep in the warmth and exclude the wind and rain. They will be light in weight and will fit together with that precision which machine techniques and accurate mathematical calculation provide, and the people who live in them will be able to arrange the spaces within their houses to suit their changing needs.

The realisation of these possibilities will take time and it may not be until the second or third generation that they come to fruition; but that makes them none-the-less important.

In this challenging situation, the work of Peckham throws valuable light on the way in which people are likely to want to use a free and changeable environment. It is not surprising that architects—excited by these technical possibilities—should look to ‘Peckham’ for help in discerning the patterns of human living. As Paul Klee saw, these patterns have a visual as well as a biological beauty—and this will be reflected in the structures which shelter them if those structures are the result of that ‘joy in construction’ which is seen so clearly in the perfection of the well-built nest.

Here is an approach appropriate to an age in which Art becomes more functional and Science becomes more human.

MICE and MEN —which throws light on the approach of the biologist

After going round the Centre and seeing something of its many sided life, visitors—and prospective staff—often ask me what the staff of the Centre are trying to do.

The apt question would be—what are we anticipating that the Centre will do to us?

That will depend upon what sort of persons we are. It will depend on how far we, through the purity and sensitiveness of the stuff we are made of, are becoming, or capable of becoming, able to ‘receive’ and to register the realities of what is around us. We have to find out how far we are prepared and able to shed the conventional channels of approach, both personal and intellectual, and allow the material at hand to impinge upon our complex sense apparatus, from which there will be woven a new synthesis of the meaning of what is seen. As biologists our material is human families. The important factor is our manner of approach to this material. The quality of approach required could not be better expressed than in the following quotation.

‘ ” We all dislike our food being shared with mice and the musky or mousey odour and flavour being associated with every mouthful that we eat, and we make combative resolves to trap and otherwise exterminate them. This is necessary hygienic, lesser humanistic knowledge. But one night when you come back late, put the key in the front door of the still house and steal up to your room, where your late supper is laid, and eat in silence your solitary meal, with the rest of the human inmates in bed and asleep; one night when your late supper is finished and a few crumbs are on the floor, there is a scratching behind the skirting board, two little beady eyes peer out from an unsuspected hole, and an inquiring little nose is in front of them,and then the whole body of a daring little mouse appears.

‘ ” He openly peers at you with those bright beady little eyes, and you try to sit as still and keep your chair from creaking, with almost as much care as if a burglar were threatening you with a loaded and well-directed pistol. Those live-looking little eyes, what is behind them? Those dainty finger-like little front paws, the little graceful, agile movements, you note them all, and in a flash, feeling the wonder of it—a little living creature, what will it do next?—the wonder of it takes possession of you. . . .

You hold your breath. . . . You sit still and are motionless…

And as you succeed, and its strange little mental confidence in you increases, you push crumbs near it, ridiculously gently, for fear it rushes from you again.

‘ ” For the moment, the wonder of the living creation holds you in its grasp; for the moment you are peeping over the spiritual fence of the vast domain of mind and life, and have pushed open the never-latched gate of its territory. Make this wonder not momentary but lifelong; make it always disinterested as it is in this moment of wonder, and you have become a naturalist. Feel towards your fellow men and women, to babies and children, as you felt for this little living creature, and these same men and women and babies and children will fill you with wonder as the other little life has done. It is this broad domain of the naturalist, riot the narrow one of the humanist, that reveals nature to us. If it has its seemingly cruel side, we must see it thus disinterestedly with the wonder and the mystery of its vast thought problem always in front of us. If the seeming cruelty has a greater and more beneficient meaning than at first appears, we can discover it only by keeping hold of this wonder, the wonder of that purposeful little creature, so much alive and as vaguely, apprehensively disturbed by our ways as we are thoughtfully awakened by its own.’ “(*The Stages of Human Life—J. Lionel Tayler, M.R.C.S., published 1921, pp. 5 and 6)

Old fashioned as may be the form in which the above picture is painted, it has caught the essence of the attitude necessary in the biologist, for it indicates that the supreme condition necessary for such work is an attitude in the observer.

If this is true for mice, how much more true for men!

I.H.P.

The Centre is now in a position to offer one or two studentships of one year’s duration to those interested in biology, sociology, medicine or education. Experience has shown that the opportunity offered is particularly valuable to those waiting to enter the University. Living accommodation is available if desired. Application should be made to Miss Langman, at the Pioneer Health Centre, St. Mary’s Road, S.E.15

THE CENTRE MONTH BY MONTH

THE ACTIVITY JIG-SAW for grown-ups and adolescents

The Centre’s winter activities are now in process of ‘organising themselves.’ The initiative comes from the members whose current interests the programme reflects. With ‘space’ serving so many varied purposes, the jig-saw of times and spaces eventually sorts itself out into a firm schedule. This is no warden or leader-planned programme. Of the weekly rhythm of activities it can be said that, like Topsy, it ‘growed.’

Badminton. In the Theatre auditorium. A game costs gd. Racquets available (but enthusiasts choose to bring their own). Evenings: regular nights agreed for adult experts and beginners (both sexes). A group is to be formed for the under-eighteens. Afternoons: mostly mothers or children. One afternoon set aside when old players help beginners. Open nights: (i.e., any member may play) Fridays and Saturdays.

Billiards and snooker. Formerly only men played. New developments are ‘Ladies’ and ‘Junior’ sections (like other games, billiards may be played either by joining one of the sections, or by buying a ticket at the cash desk for a casual game).

Camping. A wonderful season is just over. Members of the camping section are now making themselves available to advise next year’s prospective members, on equipment so that they may start saving up for it during the winter.

Centre band. A group of young men, who play by ear, provide alternative players for two dance nights a week. Also for extra dances.

Choral section. Three married couples have provided the impetus for the Centre’s first choral society which is now forming.

Concert party. ‘Grand Variety Show’—the first of the season, is booked for two end of September performances.

Dancing. Wednesday nights: for the young people. Saturday nights, everybody joins in. Also special dances-arranged by various sections. The orchestra is always ‘The Centre Band.’

Old tyme dancing. Started by two married couples last year. Quickly ‘caught fire” as those who watched joined in.

Darts. Men’s and women’s sections.

Drama. Two plays are now in rehearsal. There is a play reading group, who also enjoy theatre-going together.

Dressmaking. Evenings: with Mrs. Collins (a member sharing her skill). Afternoons with Mrs. Roberts (of the L.C.C. Evening Institutes). Started last autumn as a new venture. Has now grown to two classes.

Fencing. Mr. Sumption, expert fencer and Centre member, has just lost his class, through the call-up. We wait to see if a fencing section will develop amongst other Centre members.

Football. Started through the keenness of a group of boys. They invited three fathers to organise and train. Two teams (junior and grownup) developed last year. Now the section is in three leagues, with ‘friendlies’ arranged for those who are not in the league teams. Two F.A. coaches (young married members) are specially interested in coaching the juniors. There are two regular training nights in the gym.

Handicrafts. Last year a Monday afternoon class formed to learn leather and raffia work, lampshade and soft-toy making, with Mrs. Roberts of the L.C.C. Evening Institutes. This class has just re-formed.

Keep-fit (ladies). This class was-originally taught by one of themselves. Now feeling the need for more advanced training, Mrs. Aylward, of the Women’s League of Health and Beauty, has been asked to instruct. The pianist is a Centre member. Admission to class 3d. or 6d. including swimming. We should like to thank Mrs. Aylward for so generously donating her instructor’s fee to the Centre’s Appeal Fund.

Keep-fit (men). With Mr. Tunnicliff, Lucas Tooth Instructor and Centre member, in the gym. on Thursday evenings. For men and adolescents. Includes physical training, agility vaulting, rope climbing, ju-jitsu. Admission: tickets 3d., with swimming 6d.

Magazine (the centre). Written by members for members and gestetnered by members: appears monthly. On sale at cash desk (price 3d.). Editor: Mr. Ron. Goldsmith.

Swimming. 4d. a swim, or 8d. a week single ticket. Double ticket (man and wife) 1s. per week. The bath is reserved for the swimming group (for diving and water polo practice) for one hour on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. There are two water polo teams, senior and junior (i.e., adolescents) the juniors have been coached by the seniors. The Centre opens for swimming from 8 to 9 a.m. only on Sundays.

Table tennis. Casual tables: every evening except Wednesdays. Tickets 1d. Bats on loan. Balls on sale. The Table-Tennis section is affiliated to the Woolwich and District and E.T.T. Associations. Subscription to 4d. per week (including use of balls).

Whist drives. One evening a week. Admission 1s.

Children’s activities will be described in a later issue.

The Claude H. Leon Gift

We should like to record with thanks the generous gift of £200 from Mr. Claude H. Leon, of South Africa, which was given to us for the special purpose of buying bicycles and skates for the Centre’s children. Mr. Leon, who had already donated a very large sum to the South African gift fund from which the Centre benefited so generously, made time to visit ‘Peckham’ with his brother last year whilst on a short visit to this country.

A grandfather himself, he was particularly interested in our children, spent some time watching them out on the playground, and expressed very understanding sympathy with our need for many more strong little bicycles and roller skates that are tough enough for such continued use. In thanking Mr. Leon for the cheque which arrived this summer, we should like it to be known that his gift arrived at a very happy time. Since the war the right types of bicycles and skates have been very difficult to purchase in this country, but very good models have now become available, and we have a few on test at the moment. We hope Mr. Leon will come over to England again to see them. It would do his heart good; the children do make such good use of them.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER ISSUE

It is regretted that owing to holidays we have had to merge the September and October issues of ‘ Peckham ‘ into one.

THE PIONEER HEALTH CENTRE

GOVERNORS

- The Hon. Lady Cripps, G.B.E.

- The Lord Horder, G.C.V.O., M.D., F.R.C.P.

- The Hon. Ewen E. S. Montagu, O.B.E., K.C.

- Innes H. Pearse, M.D. (Founder and Director).

- Col. The Rt. Hon. Oliver Stanley, P.C., M.C., M.P.

- Sir P. Malcolm Stewart, Bart, O.B.E., Hon.LI.D.

- The Lord Webb-Johnson, K.C.V.O., C.B.E., D.S.O., T.D.

- Scott Williamson, Esq., M.C., M.D. (Founder and Director).

PRESIDENT The Lord Horder, G.C.V.O., M.D., F.R.C.P.

VICE-PRESIDENTS

- Gerald Schlesigner, Esq.

- Mrs. D. Winkworth.

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

Chairman Sir P. Malcolm Stewart, Bart, O.B.E., Hon.Ll.D.

Vice-Chairmen

- ]. G. S. Donaldson, Esq., O.B.E.

- The Hon. Ewen E. S. Montagu, O.B.E., K.C.

Hon. Treasurer R. P. Winfrey, Esq., M.A., Ll.B.

Hon. Secretary The Hon. Mrs. Ewen E. S. Montagu

Hon. Appeals Director Mrs. C. Frankland Moore, M.B.E.

- The Hon. Lady Cripps, G.B.E.

- Mrs. J. G. S. Donaldson

- The Rt. Hon. Walter Elliot, P.C., M.C., F.R.S., M.B., D.Sc., Ll.D., M.P.

- Mrs. B. Girouard

- Miss M. E. Langman

- Mr. and Mrs. Howard Marshall.

- The Countess Mountbatten of Burma, C.I., G.B.E., D.C.V.O.

- Mr. and Mrs. Edward Norman-Butler.

- Innes H. Pearse, M.D.

- The Lord Piercy, C.B.E.

- Arthur Rank, Esq., J.P., D.L.

- Major J. McL. Short.

- G. Scott Williamson,Esq., M.C., M.D.

GENERAL SECRETARY C. Donald Wilson, B.A.

All editorial enquiries to be addressed to: 8f Hyde Park Mansions, London, N.W.1. (Tel.: PADdington 6358).

Advertisement Representative: George Jackson, Cliffords Inn, Fleet St., E.C 4.