The examination of the diets of the different groups recorded in the preceding section shows that, on the standards taken, in the lower income groups the average diet is inadequate for perfect health. As income rises the average diet improves, but a diet completely adequate for health according to modern standards is reached only at an income level above that of 50 per cent. of the population.

As income level falls other factors affecting health change as well as diet. These are referred to later. Ignoring for the time being these other factors, one could predict from the nature of the diet of the different income level groups that there would be a good deal of ill health due to faulty diet, the incidence and degree being greater at the lower levels.

Owing to the requirement for new tissue formation in growth, children need a diet richer in first-class protein, in minerals and probably also in vitamins, than do adults. The evil effects of poor diet are, therefore, accentuated in children.

NUTRITION OF CHILDREN.

Owing to the difference in the nature of the diets, a comparison of the health of children of the lower income groups with that of children of the higher income groups, should show a slower rate of growth and a greater incidence of deficiency diseases in the former.

Rate of Growth in Children.

It is well known that stature is largely determined by heredity. The extent to which a child will attain the limit set by heredity is, however, affected by diet. Certain deficiencies of the diet lead to a diminution in the rate of growth, with the result that the adult does not attain the full stature made possible by his inherited capacity for growth. Height and weight of children are therefore sometimes taken as an indication of the state of nutrition. On account of hereditary factors, figures applying to small groups are of little value. When applied to large groups of the same race, however, comparable figures for height and weight do give an indication of the relative adequacy of the diets of the groups.

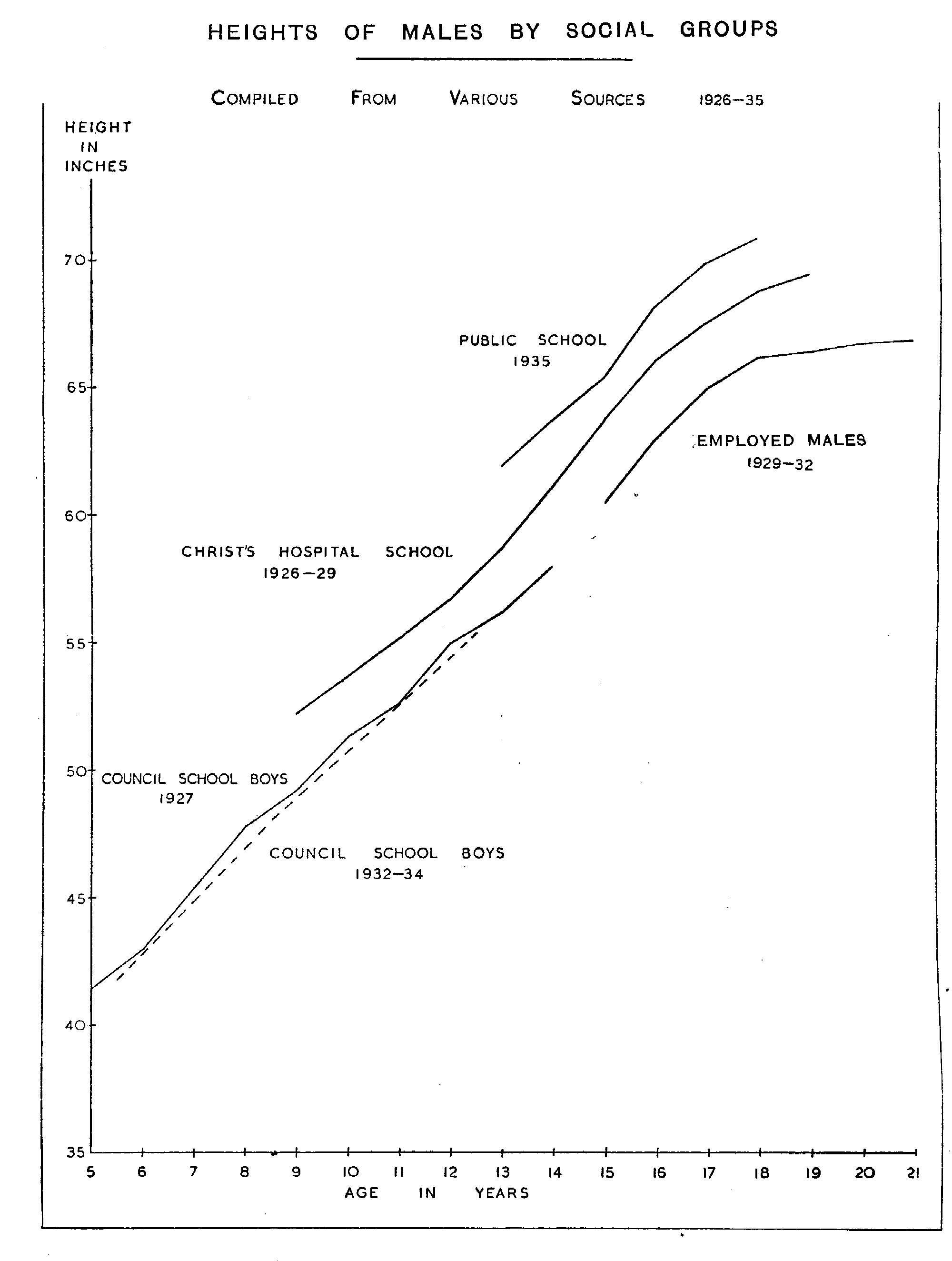

Differences in the height of children and adolescents of different classes are depicted in the accompanying graph. Table 9 shows the numbers of observations on which the averages are based. Further details are given in Appendix VII.

|

Dates at whichmeasurements were taken |

No. of observations | |

|---|---|---|

| Public School | 1935 | 307 |

| Christ’s Hospital School | 1926-9 | 16031 |

| Employed Males | 1929-32 | 2061 |

| Council School, Boys | 1927 | 12605 |

| Council School, Boys | 1932-4 | 36949 |

The children attending elementary council schools and the employed males may be taken as belonging mainly to groups I to IV ; those attending Christ’s Hospital School (17) to groups III to VI. Those attending the public school belong almost entirely to group VI, where every constituent essential to health is present in abundance in the diet.

It is seen that there is a marked difference in the heights of boys drawn from different classes. Thus, at thirteen years of age the boys at Christ’s Hospital School are on an average 2.4 inches taller than those of the Council Schools. At seventeen they are 3.8 inches taller than “Employed Males,” who may be taken as belonging to the same class as the boys in the council schools. The most striking feature of the graph, however, is the average height of the boys of the public school drawn from group VI, the highest income group. Further figures are needed for other public schools of the same class to show whether the heights recorded here are true averages for boys in this class of school.

The British Association anthropometric data of 1883 (6) showed that the average height of boys of thirteen and a half years in an industrial school was 2.6 inches below that of artisan boys of the same age, and 5.8 inches below that of boys of the professional class. It appears that in the last fifty years, though the average height for all classes has risen, there has been no marked change in the order of differences between the classes.

These differences in height are in accordance with what would be expected from an examination of the diets in common use in these classes. In the lower income groups the diet is relatively deficient in the constituents required for growth. Too high a proportion of the diet consists of carbohydrate rich foods, which contain very little bone and flesh forming material.

Of course tall and short individuals are found in all the groups. We are, however, considering here average diets and average heights. In each group some diets are better than the average and some worse. The better diets in the lower groups support a faster rate of growth. On the other hand no diet, however good, would enable an individual to exceed the limits of growth set by heredity. Short stature in the wealthier groups is in most cases inherited.

Incidence of deficiency Disease in Children.

Owing to the varying standards of health assumed by different observers, those who accept the average as normal and regard as ill-health only what is markedly below the average, find little malnutrition or disease arising from it. On the other hand, those who adopt the physiological or ideal standard, as defined on page 12, recognise a great deal of preventable ill-health. There are no universally accepted standards of health based on agreed systems of measurements and clinical signs. Unfortunately there are too few observations on any reasonable standard. In the absence of sufficient comparable data, all that can be done is to give illustrative examples of observations of ill-health due to faulty diet.

It will be sufficient for the present purpose to consider three diseases: rickets, bad teeth and anaemia. It is known that diet is an important factor in the etiology of these.

Rickets.—Figures for the incidence of rickets given by different observers vary very widely owing to differences in the standard adopted and in the method of diagnosis. If the diagnosis be made on clinical examination only, the number found will usually be less than if a radiological examination be made, and in clinical diagnosis the number will depend on whether only obvious gross deformities are considered, or minor degrees of imperfect development are included. For this reason the figures given by different observers for the incidence of this disease are not comparable. Thus, for example, the incidence of rickets in L.C.C. schools was estimated at 0.3 per cent, in 1933 (25). On the other hand, in 1931 a special examination of 1,638 unselected school children showed that 87.5 per cent, had one or more signs of rickets (5).

With such imperfect data it is impossible to make any accurate estimate of the incidence of this disease in the country generally, and still less of differences in incidence in different social classes. There is, however, no doubt that though minor degrees of rickets are still prevalent and probably more prevalent in the poorer classes, the incidence of gross rickets with marked bony deformities, which are obvious even to the lay observer, has markedly decreased in recent years. The deficiencies in the diet to which this condition is due are now well known, and this knowledge has been applied to the reduction of the preventable disease.

Bad Teeth,—It is now generally believed that there is a close correlation between dietary deficiency and dental caries. Though there is still some difference of opinion as to the relative importance of the dietary factors involved, there is no longer any doubt that the diets of the lower income groups, which are markedly deficient in minerals and vitamins, are not such as to promote the growth of sound healthy teeth. Whatever other causes of dental caries there may be, one would expect to find poorly developed teeth and a high incidence of caries in children reared on such diets.

About 80 per cent, of the deciduous teeth of British children are imperfectly developed (hypoplastic) (31). Since this defect may be established before birth, it may in part be due to dietary deficiency in pregnancy. But the fact that the incisors, which are in the most advanced state of development at birth, are usually better calcified than the later developed molars, suggests that the dietary deficiency may be even greater in early childhood than before birth.

Nutritional Ancemia.—Records of the incidence of nutritional anaemia would give a good indication of the adequacy of the diet. Unfortunately the incidence of anaemias and the extent to which they are due to causes other than diet, cannot be stated with any degree of confidence. Reports of School Medical Officers based merely on the appearance of the child show incidences of from 0.25 to 3.76 per cent, in the children examined, but an examination based merely on appearance would not show minor degrees of ansemia such as could be caused by lesser degrees of malnutrition.

The haemoglobin content of the blood is the only true standard. In a special investigation in which the haemoglobin of the blood was determined in two groups of children: (a) in a routine medical inspection group, and (6) in a group selected because of poverty to be given a supplement of milk, 75 per cent, of the children in (a), and only 51.5 per cent, in (b) showed a haemoglobin value over 70 (21). For a perfectly healthy child the value should be at least 90.

There are available the results of one investigation in which children of pre-school age of the poorest class are compared with children of the same age of the well-to-do class. Of the former, 23 per cent, were definitely anaemic, and of the latter, none (43).

It is possible that a minor degree of anaemia, indicating a minor degree of ill-health in children, is more common than is generally supposed. An extensive enquiry to show the relative frequency of anaemia in the children of groups I and II compared with that in groups V and VI would throw much needed light on the relative state of health of the children of families at different economic levels.

We have considered three characteristic signs of malnutrition in children, rickets, bad teeth and anaemia. These are fairly widespread in the lower income groups, the only groups in which extensive observations have been made. In these groups growth is slower than in the high income groups. It is interesting to note that these diseases and stunted growth are attributable to lack of those dietary factors, viz., first class protein, minerals and vitamins which are the constituents of the diets shown to be deficient in the lower groups (pages 33-36).

Incidence of infective Disease in Children.

There is evidence to show that these same deficiences affect resistance to some infectious diseases, such as pulmonary and intestinal disorders in young children. Children with rickets show a higher incidence of complications and a higher death-rate from some common diseases, such as whooping-cough, measles, and diphtheria than do those in the same environment without rickets (27). A recent observation seems to indicate that non-pulmonary tuberculosis is less frequent in children who drink relatively large quantities of milk than in those who consume little milk (8).

NUTRITION OF ADULTS.

It has been established in nutritional studies that the constitution of the adult is affected by the state of nutrition in childhood. The rate of growth and the health of children have been shown to be below the optimum. The result of this should be traceable in poor physique in adult life. There is much evidence of the effect of malnutrition in selected groups of male adults, e.g., in certain occupations and in army recruits. There are, however, few comparable data on adults at different income levels. The state of nutrition of the adult is therefore not referred to at length. It will be sufficient to choose two diseases as illustrative examples, one infectious and one non-infectious, in which diet is an important factor.

The most significant infectious disease illustrating the influence of nutrition on susceptibility to infection, is tuberculosis. Infection is very widespread and in the great majority of cases it is the resistance of the individual which determines the extent to which the disease develops. Striking evidence of the influence of diet on resistance is afforded by the experience of Germany during the recent war. In the highly industrialised parts of the country where the food shortage was most acute the tuberculosis mortality showed an enormous increase. In Saxony it was almost doubled. This increase was accompanied by an increased virulence in the type of the disease (3, 1).

The Registrar-General’s Report of 1927 shows that the mortality rate from tuberculosis amongst occupied males was nearly three times as high for unskilled labour as for the higher ranks of business and professional life (40). It is probable that the most effective line of attack on tuberculosis is by the improvement of diet.

For the health and physique of the rising generation the health of women is more important than that of men. One of the common results of malnutrition is anaemia, though, of course, anaemia may arise from other causes. It is much more common in women than in children and men. Its frequency in women is attributed to the extra demands for iron in women of the child-bearing age. In an investigation in Aberdeen in 1933, it was found that of about 1,000 women of the class of groups I, II and III, 50 per cent, were anaemic, 15 per cent, being classed as ” severely anaemic ” (12). In 1935 in the examination of 368 London mothers of low economic status, it was found that less than 30 per cent, had a normal haemoglobin level (26).

There are no comparable figures showing the incidence of anaemia in the higher income groups. Further, causes other than poor diet predispose to it. All that can be said, therefore, is that some degree of anaemia is common in the lower income groups, that it is, at least in part, preventable, and that diet is an important factor in its prevention.

INFLUENCE OF FACTORS OTHER THAN DIET.

In considering the different types of ill-health referred to above, it has been difficult to assess the relative importance of diet and other factors. As income level falls, housing and other environmental conditions change. The importance of these for health is now fully recognised. Even apart from the known deleterious effect on health, the social evils of slums are so great that any suggestion that improvement of housing is of less importance than other social reforms is to be deprecated. The advantages to be obtained by better housing, as has been shown by M’Gonigle (30), are limited by inadequacy of diet, and the maximum advantage can only be obtained by improvements in both.

Hereditary differences also profoundly affect growth and susceptibility to some diseases. No individual can pass the limits set by inheritance. The most that can be done by diet or other environmental factors is to enable the individual to attain his full inherited capacity for growth and health.

Feeding Tests with other Factors controlled.

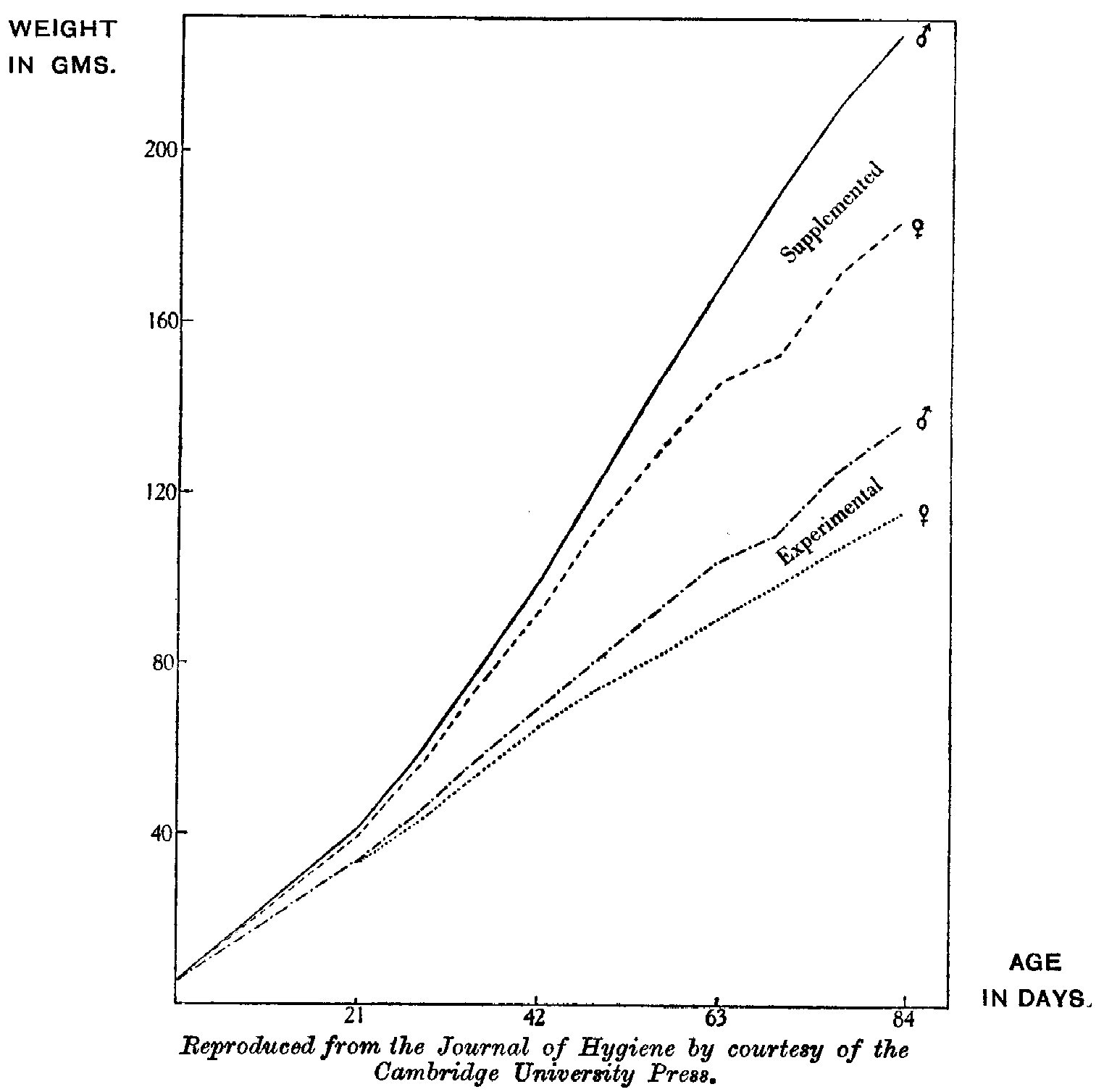

The effect of diet can, however, be studied by feeding experiments with animals under conditions where diet is the only varying factor. Hundreds of such experiments have been made on closely related animals with, as far as possible, the same inherited characteristics and kept under the same environmental conditions. McCarrison, who has made a life study of nutritional problems, especially those relating to India, took several groups of rats and fed each group on a diet in common use by one or other of the various tribes in India. These rats were all kept under the same environmental conditions. He found that the physique and incidence of disease in each of the groups corresponded to an astonishing degree with those found in the tribes whose diets were copied and that there was a similar corresponding incidence even in the case of diseases which, at that time, were not usually thought to be connected with faulty diet (28). A similar experiment with modifications to suit this country has since been conducted in Scotland (36). The rats in one group were fed on a diet somewhat similar to that of income group I in the present survey. Other closely related rats were fed on the same diet supplemented by an abundance of milk and as much green food as they cared to eat. These additions made good all the deficiencies of the average group I diet, making it as adequate for the maintenance of health as the diet of group VI. The following graph shows the relative rates of growth of the young animals of the two groups.

Not only were the rates of growth markedly divergent, but the death rates of the two groups differed correspondiagly. The mortality to 140 days of age on the supplemented diet was 11.6 per cent., while for those on the experimental diet the rate was 54.3 per cent. This heavy death rate was due mainly to epidemic infections to which both groups were equally exposed.

Such experiments with rats, of course, do not carry the same weight as observations on human beings. The dietary requirements of man and rats are not identical. Observations, however, have been made on two tribes, the Masai and the Kikuyu, living in Africa under the same climatic and housing conditions, but with very different diets (35). The diet of the Masai is rich in first-class proteins, minerals and most vitamins, though faulty in some other respects; the diet of the Kikuyu is rich in carbohydrates but relatively poor in most other constituents. The latter corresponds, roughly, to the average diet of groups I and II of our own population, A medical survey of the two tribes showed that the males in the tribe with the former diet were, on an average, five inches taller than the males of the latter tribe. There was also a striking difference in the incidence of disease in the two tribes. Bony deformities, somewhat similar to those found in children who suffer from rickets, carious teeth and pulmonary and intestinal diseases were more than twice as prevalent in the tribe on the diet poor in proteins, minerals and vitamins. These observations, though they do not refer to the people of this country, give confidence in accepting as substantially correct the general picture given here.

Effect of Improvement of Diet on Rate of Growth and Health.

Tests have also been carried out with children in this country. As far as they go these confirm the results obtained on animals and native tribes.

In 1926 observations were made on the effect of supplementing the diet of boys in an industrial school. The diet without the supplement was assumed to be adequate for health. It was found that the addition of milk increased the rate of growth for the period of the test, the increase per twelve months in boys on the diet alone being 1.84 inches, while in those receiving extra milk it was 2.63 inches (11).

These results, however, cannot be applied to children under home conditions. In 1927, therefore, a series of tests was carried out in Scotland in which about 1,500 children in the ordinary elementary schools in the seven largest towns were given additional milk at school for a period of seven months. Periodic measurements of the children showed that the rate of growth in those getting the additional milk was about 20 per cent, greater than in those not getting additional milk. The increased rate of growth was accompanied by a noticeable improvement in health and vigour (33, 34). This experiment was twice repeated by different observers who obtained substantially the same results on numbers up to 20,000 children (22, 23).

Tests with even more striking results have been obtained in other countries, where the average diet is inferior to that in this country. Tsurumi has shown that in elementary schools in Tokyo the addition of 200 c.c. (about 1/3 pint) of milk to the diet for six months caused a marked acceleration in the rate of growth, the gain in weight being 86 per cent., and in height, 16 per cent, more than in the controls. It was reported that the children who received milk “had improved complexions and glossy skins,” and that “they became more cheerful, attended school more regularly, and were more successful in athletic contests than the corresponding control children” (45). Turbott and Holland, in New Zealand, found that a supplement of 1/2 to 1 pint of milk daily given to Maori children caused an increase in rate of growth such that they gained twice as much in height, and 2 1/2 times as much in weight as the controls (46).

The results of these tests on animals under experimental conditions and children under ordinary conditions of everyday life, suggest that, to whatever extent heredity and environment account for differences in health and physique of different classes, it would be possible to effect a considerable improvement in the health of the children of lower income groups by improving the diet.