Towards A Real Strategy For Health

Professor Peter Townsend, Margaret Buttigieg, Professor Sir John Crofton, Dr Lorna Arblaster, Stephen Maybury, Christine Davies, John Battle MP

Report from Conference on 26 February 1994 arranged by the Socialist Health Association and the Labour Housing Group

Battlelines: The Construction Of An Alternative, And More Effective, Health Policy To That Of The Conservative Government

Professor Peter Townsend, Emeritus Professor Of Social Policy, University Of Bristol

Thinking in the Labour movement about policy has always been bedeviled by conventional definitions of subject areas. This applies to the Parliamentary party as much as it does to Labour organisations. Ministers and Shadow Ministers are not expected to stray outside their brief, even when the subject or the problem requires action by several departments, and not only the resolution of a common approach and a common set of priorities.

This poses a political problem of the very first order for strategies on health, and really underlies what this particular day conference is all about. Because we have to attend to the ways in which we can encourage not only a wider thinking about health, but also how the devil we manage to concert strategy, and political and ministerial responsibility. All my life I have felt that that has been relatively neglected. We stumble from one period of government to another without really confronting the problem of how we get collaborative action by different departments of state, let alone concerted action involving people who really know about health and preventive health at the grass roots. The process by which great issues come to be restricted to lame and piecemeal change is highly political as well as social. Those practising health care want independence from interfering politicians, almost as much as politicians want issues of health to be narrowly circumscribed to specialised, restricted and hence mare easily controllable activities.

It is on some such lines that health policies, and political and administrative practices in relation to health have became medicalised and individualised. Unless we recognise this general problem, we cannot even work out small desirable changes likely to be effective. Too often we “spit into the wind” hoping that somebody will take our ideas into account.

Even the idea of “health” has became somewhat corrupted. Although we have to recognise that the detail can be subtle and complex, the core of a medical meaning of health still remains, and I quote, “the absence of clinically ascertainable disease”. This produces of course a kind of divorce between comprehensive and medical meaning – a rupture of reality and truth. The difference is easy to illustrate. Ask anyone about their state of health today. They will not only reproduce statements passed an to them from their doctors or learned dutifully from medical contacts, they will speak of levels of energy, satisfactory sleep, vitality, comfort, enjoyment of activity, peace of mind, states of happiness and fulfilment, and the way they’re getting an with others and doing a useful job in their family relations or their community relations. This is what “health” means in a comprehensive sense.

The medically controllable aspects of health are indeed important, but socially and environmentally, and economically controllable aspects may be equally if not more important.

These are I think familiar themes to an audience like this one. Familiarity though makes them no less relevant to today’s conditions. I haven’t had time enough to do much mare than indicate the real scope of our problem. We must not allow ourselves to forget that general context in attending to any specialised problem or question -whether it be trying to find a solution to cancer, or to AIDS, or to any other major problem. The medical profession, and those outside the medical and nursing professions who care about preventive health, and the right structures, and the right conditions in society in which to achieve a healthy population, have to work together because they are two, sides of the same coin. That is my theme.

Labour’s Shadow Ministers are making clear the gulf which divides them from Tory thinking on health. If we look at the responsibilities or the briefs of both the Health Ministers and their Shadows, Labour has made quite clear its determination to abolish the hospital trusts, reverse fund holding, and bring the internal market to an end. Labour will remove subsidies from private health services, and hence counter and perhaps reverse, the growth of private medicine and two tier service. Many of us want to oppose the growing emphasis an competition rather than on cooperation. Many of us want to oppose the growing emphasis on business rather than on service. A new publication by Sir Douglas Black has called attention to the ideological background, the theoretical background, which persuades too many people to go in the direction of market values and market concepts of measurement and reward. That has to be brought under control.

I want to call attention to some of the difficulties involved in re-establishing the principles of the National Health Service, but also to put potential new policies into a wider context. I may be repeating things well known to people here, but let me pick out what I regard as the continuing argument, and a dignified and scientific exposition at the same time, about the realities of trying to do better for the health of the population.

A lot happened, of course, before the publication of the Black Report. Nonetheless it has provoked and prompted a continuing stream of discussion about a very large issue, which Ministers of Health and the professionals dealing with health care and the treatment of ill health, cannot really do much about.

There were two distinctive conclusions of that Report, which we ought to hang on to in relation to the succession of evidence that has since appeared. First of all, while social selection and individual choice of lifestyle explained part of the observed inequalities in health, material deprivation was much the most predominant causal factor. The research working group went on to reach a second conclusion – that although the direction of scientific argument was indisputable the part played by different elements of deprivation itself remained to be demonstrated. In a way this is also what this conference is about. We are discussing one major aspect of material deprivation to do with housing. There are other aspects of material deprivation which also deserve our close attention in developing a full health policy.

I have referred briefly to the research evidence. For those who haven’t had the opportunity to become familiar with it, it is vast. There have been a number of reviews, at least ten to my knowledge, of the research evidence produced not only by 1980, when the Black Report materialised, but subsequently, and there are still reports coming out. The most recent was in the British Medical Journal in November 1993 by Davey Smith and Egger (1993). There is the third edition of the Penguin version of the Black Report and Margaret Whitehead’s The Health Divide (published in November 1992). We are already grumbling because we think we will have to prepare another edition soon to take account of some of the international developments which are changing the scope and shape and hard hitting nature of the argument.

In the 1990s the argument of the Black Report has enlarged and become more powerful. Some people believe that once you’ve done a piece of work in research then there it stands for all time. That is not true of different aspects of material deprivation in relation to health. Some uncertainties in the range of evidence have indeed been cleared up. For instance, through the longitudinal surveys following up a sample of the people who filled in the census, investigators have shown that inequalities in health after retirement are as significantly related to material deprivation as they are before retirement. Other investigators have examined different gradients from the rich to the poor, or from the professional and administrative occupational classes down to the poorest manual classes. The really meticulous studies which have been completed produce even sharper evidence of the links between deprivation and ill health than the official statistics represent, because of errors in census statistics about occupation, for example. There is also a random element in classification which tends to reduce extreme differences in the distribution. There is Marmot’s famous study of Whitehall civil servants. As you go down the grades of the civil service mortality increases steadily. The gradient is linear in character through 17 grades according to salaries. From top to bottom the ratio of deaths is 3 1/2 to one.

Such investigations have removed some of the objections to the theory of material deprivation causing ill-health. The theory is now far more powerful than it was when it was first put forward. Moreover, current trends are vitally important for everybody to recognise. Our problem is not a question of inequalities which have persisted through generations which ought to be put right, but rather that inequalities are growing fast. They are growing whether we measure deprivation, whether we measure income, or whether we measure almost any aspect of health. When I say any aspect of health, that seems now to apply to all the major causes of mortality – as analysed in the ten yearly reports by the Government’s medical statisticians. It also seems to apply to measures of chronic sickness, disability and growth or development.

I was one of the three authors of a new report published by the British Medical Journal, about the North of England (Phillimore, Beattie and Townsend, 1994). This report covers 678 different wards in the Northern region – from the most affluent at one end to the most impoverished at the other. One of the interesting conclusions of the first stage of that work (published in a book in 1987) was that 69% of the variance in health (as measured not just by mortality, but also by low birthrate of infants, and by the proportion and number of people who had disability within the local population) was explained by a mere four indicators of material deprivation.

Before describing the second stage of the work, I must emphasise how remarkable this conclusion seemed at the time. It was a crude measure which needed refinement. We realised we needed a somewhat more comprehensive scientific approach, and are frustrated by having insufficient and inadequate census data (it’s not too bad for housing). We don’t have indicators on a national basis about working conditions which are every bit as important as home or housing conditions in investigating the correlation between deprivation and ill-health. We are not able to relate environmental pollution to the same individuals and the same households as are described in the census. So we cannot amalgamate the argument about deprivation in relation to the multiple effects of bad housing, bad working conditions, and bad environmental pollution. If only we could put those three together we would have a more rational basis for action. Within material deprivation we could identify the biggest causes of premature death and disability. If housing is really the dominant factor then that is what we would have to attack in terms of policy, and make improvements. If it turns out that it is work conditions which account for most of the inequalities in health and premature death, then that is what we would concentrate on, and we’d do something about that.

The nature of this argument about material deprivation is of vital, indeed crucial, importance to policy. Repeatedly there is new evidence being published. In the new North of England study, for example, instead of being able to take only three years data to show the variation (in 1987 we had information for 1981 – 1983 inclusive), we could now take 10 years of evidence – from 1981-1991. That allowed us to reach rather firmer conclusions about infant mortality for example. You will appreciate that the number of infants dying in certain wards of only 10,000 population, is very few – and there is an element of chance about the number of deaths in a small area compared with other small areas. That tends to reduce the confidence with which one can say there is a connection between material deprivation and premature death. With ten years accumulated data we were able to demonstrate that the evidence about the connection between material deprivation and ill-health was even stronger than previously believed. Our four self-same crude indicators of material deprivation now explained not 69% of the variance but 85% of the variance.

I want to end with the international perspective. Some people feel this is new and an unnecessary complication. They look wearily at me when I talk about it. They say they have enough on the agenda already – why bring in the international perspective? The problem is that we cannot any longer ignore that perspective in arguing the scientific case or in trying to produce remedies over which we have some control.

Let me explain. There are two sides to it. One is that “polarisation” of health is a common trend internationally. The other is that there are international causes of that trend. There are widening inequalities in health in a number of countries as well as in the UK. In the UK the evidence from the northern region shows that relative inequalities are widening, meaning that the professional classes’ death rate is falling much faster than that of the poorest classes of the population. But it also shows that amongst the poorest tenth or fifth of the population some are experiencing an increase in mortality. We found that in three or four of the age groups that we were examining in the North of England, absolute mortality has increased during the 1980s. The Chief Medical Officer had already produced some of this data for age groups in the population as a whole.

The phenomenon of increasing inequality in mortality is now supplemented among some poor groups by increasing absolute mortality. This new relationship between the relative and the absolute is also reflected in living standards as confirmed by government statistics. The latest edition of Social Trends published in January demonstrates that that is certainly the case for the poorest 10%, whether disposable income (after tax) is measured before housing costs or after housing costs. And the balance of evidence for the next 10% shows, in my judgment, the same thing. So the evidence is not just that inequality is becoming wider and the richer become much richer as a result of tax changes and a deregulated market, but that the poorest groups in the population are worse off absolutely and not only relatively.

This is the crucial point about social trends. Our biggest problem is in dealing with “social polarisation”. What is causing it? It is not enough just to say we’ve got these inequalities and we must do something here, there and everywhere to change national policies. We’ve got to try and work through the influence of the international market. In joining Europe we are expected to abide by the common market rules of market behaviour, and this will mean that countries with an expensive welfare state must trim that welfare state in order to have a “level playing field” of competition. We have the IMF and the World Bank saying, not only to the rich countries as they did to the UK in 1976, that there should be lower public spending and more privatisation. The Labour Government accepted the terms of the IMF arrangement to cut its public expenditure. This turned out to be one of the biggest cuts in public expenditure in the last 20 years – perhaps the biggest proportionately in one single year. The IMF and the World Bank have these policies. They are called structural adjustments when they are applied to Africa or S E Asia, but they are the same monetary policies as are being applied worldwide. They are believed to suit the growth of the multinational corporations.

People will say that this is far away from the interests they have in health, but it is not. Policies which bring about low wages, homelessness, more unemployment, lower wages, the decline of the real value of benefits relative to average earnings and in real terms, even the problems of drugs in the inner cities created by global drug operations, are shaped by more powerful forces in the international market. We’ve got to get used to tracing the connections to our local and regional problems, not just of poverty but of health too. National governments are no longer capable of controlling all those factors.

This brings us back to an old conclusion in a new form – we have to devise a health policy outside the national health service or we have to draw up a larger complementary package of polices. Two complementary sets of policies have to be recognised and acted upon at every level. GPs and everybody else have to operate on two fronts simultaneously – yes, there are responsibilities to patients, but there is an equal responsibility to the wider community. In the interests of good health we have to keep pressing for good housing, for good working conditions, for better air and quality of water, and rights, facilities and services and decent minimum living standards for children, men and women and each and every minority.

Yes, it is difficult to wear these two hats. It is difficult for any of us whether we’re people who are arguing in the constituencies, or whether we are operating as professionals. But this is the mere acknowledgement of the scientific lessons which can be drawn from the facts. This is what the politicians in parliament have got to do too – they’ve got the problem of trying to find some kind of rapprochement, some kind of priority between those two objectives or functions. This means we need some kind of health development programme for the country as a whole (the Black report originally put forward the idea of having a health or social development council at the heart of government to pull together the different strands of policies for health development). Now that kind of organisation is needed at an international level as well. That corresponds with the search for more democratic international organisations and a programme to bring the multinational corporations under greater control, and to moderate the abrasive and absolutely destructive monetary policies of the IMF, the World Bank and the G7 nations.

References

- The Black Report (1980) Inequalities in Health, Report of a Research Working Group, London, DHSS.

- Black Sir D (1993) “Deprivation and Health”, British Medical Journal, Dec.

- Black Sir D (1994) “The NHS: a business or service? Threatened values”, Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, 24, pp 7-14.

- Blaxter M (1990) Health and Lifestyles, London, Tavistock Routledge.

- BMA (1987) “Mortality and Geography”, Population Trends, pp 16-23.

- Carstairs V and Morris R (1989) “Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales”, British Medical Journal, 299, pp 886-889.

- Cm 1986 (1992), The Health of the Nation: a strategy for health in England presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Health, London, HMSO.

- Davey-Smith G, Bartley M and Blane D (1990) “The Black Report on Inequalities of Health: ten years on”, British Medical Journal, pp 373-377.

- Davey-Smith G and Egger M (1993) “Socioeconomic differentials in wealth and health: widening inequalities in health the legacy of the Thatcher years”, British Medical Journal, 307, pp 1085-1086.

- Goldblatt P (1989) “Mortality by social class, 1971-1985”, Population Trends, HMSO, pp 6-15.

- Loewenson R (1993) “Structural Adjustment and Health Policy in Africa”, International Journal of Health Services, 23,4, pp 717-730.

- Marmot M G (1986) “Social inequalities in mortality: the social environment”, in Wilkinson R G ed. (Op Cit).

- Marmot M G , Kogevinas M and Elston M A (1987) “Social/ economic status and disease”, Annual Review of Public Health, 8, 111-135.

- McCarthy P, Byrne D, Harrisson S, and Keithley J (1985) “Respiratory conditions: effect of housing and other factors”, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 39, pp 15-19.

- Phillimore P, Beattie A and Townsend P (1994) ‘The widening inequality of health in Northern England, 1981-1991″, British Medical journal (30 April) .

- Townsend P (1993) The International Analysis of Poverty, Milton Keynes, Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Townsend P, Phillimore P and Beattie A (1987) Health and deprivation: inequality and the North, London, Croom Helm.

- Townsend P, Whitehead M and Davidson N eds. (1992) Inequalities in health, the Black report and the health divide, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, Penguin Books (Third edition, October).

- Whitehead M (1987) The health divide: inequalities in health in the 1980s, London, Health Education Council.

- Wilkinson R G ed. (1986a) Class and health: research and longitudinal data, London and Tavistock

- Wilkinson R G (1989) “Class mortality differentials and trends in poverty 192181”, Centre for Medical Research, University of Sussex, journal of Social Policy, 18, 3.C

Dimensions Of Disadvantage: Housing, Health And The Child

Margaret Buttigieg Director, Health Visitors’ Association

“The homeless make up a group that is poorer than the poor; all of us need to help them. We are convinced that a house is more than a simple roof over one’s head. The place where a person creates and lives out his or her life, and also serves to found, in some way, that person’s deepest identity and his or her relations with others. ”

Pope John Paul II

In the 1970s indications of the disadvantage experienced by some children because of their social and family circumstances were just beginning to appear and be acknowledged by British society. The information emerging from the National Child Development Study, which followed the progress from birth to maturity of all children in England, Scotland and Wales born in the week 3-9 March 1958, showed a vast catalogue of difference between the way of life of what was termed “disadvantaged” children and their families and those families and children considered to be “ordinary”. The literature indicates that a number of eminent people were surprised at these findings, for there was a belief that since the Second World War, the emergence of the Welfare State meant that all people were now more equal.

A number of books were written at this time drawing attention to these differences and the revealing results of the National Child Development Study. These included Born to Fail by Peter Wedge and Hilary Prosser, which was a short, very readable report written in 1969, drawing together the latest information from the national study and clearly reporting the striking differences in the lives of British children. Another was entitled Unequal Britain and was a report written by Frank Field, then the Director of the Child Poverty Action Group, on the Cycle of Inequality in Britain. Both these reports revealed that despite a growth in national wealth the age-old inequalities remained with class differences in all aspects of life from income earned to status at work, in housing and in health and finally in death. Nicholas Bonsanquet, writing in 1972, said, “Class difference in opportunities for life and health start at the cradle and continue through the life span.

One needs to ask whether this has really changed today?

Twenty years on, sadly it seems we may have made few strides forward. The evidence today on the position of those disadvantaged families and the children living within them is the same or in fact very much worse. Indeed it is clear that there has been a considerable increase since the 1970s in the number of families, households and individuals living in poverty.

Over the last twenty years, a number of reports and articles have been published such as the Black Report (1982) and The Health Divide (1987) all revealing similar findings and highlighting the links between social background and inequalities of life experience. As the literature circulated to advertise this conference today clearly states, there is an association between poor or inadequate housing, homelessness and temporary accommodation, and also physical and mental ill-health which is widely recognised. Housing, as a vital part of our welfare system, the programme also suggests, is being systematically dismantled as a public service. It appears that similar could be said of the health service as we continue to see wide inequalities in the services offered to different sections of society, continued cutbacks and a continuing reliance on health care in the community more often than not provided by relatives and friends of those requiring the care.

If further evidence of the links between disadvantage and health is required, the following quote from Sir Donald Acheson, the previous Medical Officer of Health, in his final report The Public Health 1990, certainly suffices, “The issue is quite clear in health terms: that there is a link, has been a link, and I suspect will always be a link between deprivation and ill-health … the clearest links with the excess burden of ill-health are: low income, unhealthy behaviour and poor housing and environmental amenities.

There is another issue here, how is health defined? As health visitors we take a wide, holistic view of health based on the WHO definition of health. It is probably questionable whether the present government see health in the same terms.

The publication in 1992 of a strategy for health, the “Health of the Nation” placed health and health promotion firmly back on the political agenda. But, it is indicated in that document that the wider health issues, especially those of poverty and inequalities in health, are difficult to address and as stated by Claire Blackburn, a research health visitor, in a number of recent articles and books, they are basically just ignored.

Whilst the importance of publications such as “Health of the Nation” is to be acknowledge, the failure to address issues of poverty and inequality and to take such an individualistic, victim blaming view of health as the report does, is of concern.

Health visiting has its roots in the public health movement of the last century and come into being as a response to the social conditions and poor health experienced by the working classes. Improvements in health did occur, not just as a result of the health visitor’s work but from efforts from a wide range of sources. The need, however, for support and guidance from someone such as a health visitor for those families in vulnerable circumstances, remains today. Past history shows the importance of interagency working in this area and many more recent studies ego Sheffield 1993, Oxford 1992 show that where problems of working together have been addressed and where proactive inter-agency work has been introduced, some success is achieved.

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the links between children’s health, poverty, poor housing and homelessness. Evidence from Health Visitors’ Association members working with families and children living in poor circumstances clearly shows these links. I am grateful to the Associations’ Special Interest Group for Housing and Homeless for their help.

In the Great Britain of the 1990s, all health visitors, no matter where they work, have experience of clients living in poor circumstances having been made redundant, become unemployed or suddenly found themselves homeless often through no fault of their own. Some health visitors, in places like Oxford, Manchester, Sheffield and in London are working specifically with the homeless and those in poor housing, in an effort to ensure they receive adequate primary and community health care services. The Health Visitors’ Association has an extremely active Special Interest Group for Health Visitors Working with Homeless People. This group, established in 1985, has been responsible for initiating much of the health visiting work in this area and acts as a reference point for the wider membership.

The literature on the effect of poor housing and homelessness on children’s health suggests three headings.

Table 1

| 1 | Mental/emotional health |

| 2 | Physical health |

| 2 | Social health |

Mental and emotional health

Children’s health is influenced by that of their adult carer(s). If improvements are made in the health of the parents, especially that of the mother, then a child’s health improves. Depression, stress, isolation, lack of self esteem and alcohol abuse as well as family disharmony and violence are among the issues that may effect adults living in poor circumstances. In a recent study of homelessness in Oxford, depression and stress were found to be the greatest health concerns effecting both parents and children. Similar results were found in a study in Sheffield (1993) where 55% of mothers said they were depressed and found it difficult to cope with their children. Many also stated that they felt their lifestyle was not healthy and were aware that their smoking had increased as a stress reliever. In describing her feelings, a health visitor working with homeless families in a seaside town said: “A lot of people are under enormous stress especially when they live in winter lets. The strain is awful and it is difficult to give health advice when they do not have the facilities. Sometimes you have to make a choice between smoking and child abuse. What can I do, alone?”

Marital partnership disharmony and the often resultant violence may be the reason for a families homelessness but can themselves be a cause of further stress. The following quote from a woman, separated from her partner and living in bed and breakfast with three children under five, provides a useful illustration, ‘We barricade ourselves in at night, especially at weekends because of all the drunks and junkies; it is terrifying and the noise is terrible. I keep a bucket in my room so that the kids do not have to go out to the toilet, or me for that matter.”

Such occurrences lead to isolation and further stress and to a lack of self esteem which can disempower and demotivate individuals.

Racism can also be a resultant factor. A disproportionate number of families from ethnic minority groups are homeless and are singled out as different either because of their nationality or indeed because they are homeless.

The effect on a child’s behaviour of their parent(s) emotional distress has been noted in a number of studies. In the 1993 Sheffield study, 83% of those contacted said they experienced behaviour problems with their children. In the Oxford study, 50% of those contacted said their children were experiencing sleep disturbances and over 50% said their children were bedwetting.

The Sheffield study published in January 1993, was particularly interesting as it specifically addressed the health needs of children living in temporary accommodation and showed different health effects from different types of accommodation. Bed and breakfast accommodation was found to have the most severe effect on children’s mental health. The study concluded that more mental health input and support was required by families living in temporary accommodation and that there was a need for greater flexibility in this area. For health visitors the need to offer support to such families is great and the concern that a non-accidental injury may occur to child because of the parent(s) stress always around.

Physical health

Poor housing and homelessness can have both immediate and long term effects on children’s health. The dampness prevalent in poor housing and the lack of, or type of, heating used leads to an increased risk of upper respiratory tract infections and can accentuate other concurrent respiratory problems such as asthma. The closeness of living conditions and the lack of washing facilities or hot water means that illnesses like diarrhoea and vomiting and infections like scabies (which is known to be on the increase) spread rapidly. The following quote comes from a homeless family with two school aged children living in one room and sharing a bathroom and toilet with many other residents: “Basically the kids are fine but they both have asthma and it is worse since we have been here. If I can keep them well, it is okay but once they get a cold or the like, its impossible and it goes through all of us. The other week the youngest had an upset tummy, and then we all got the runs. Everything had to go to the launderette, it was such hard work.”

In 1986, when a number of health visitors were questioned in a Health Visitors’ Association/Shelter project and asked to comment on the health of the homeless within their caseloads, the results showed a high incidence of viral infections and the common childhood ailments as well as gastroenteritis, scabies etc. Uptake of routine immunisations is also known to be reduced for those families living in temporary accommodation. The following quotes illustrate well the difficulties:

“There should be somewhere where we can wash the babies bottles and things. I have got to do it in the bathroom and I am never sure who has been there before me.”

The doctor gave me some Diarolyte for the baby. I had to make it up in the morning to last the day because I had nowhere to do it once breakfast was finished. I was always unsure if the water was boiling.

Bed and breakfast or one room living means that the ability of a parent to provide an adequate diet for their child is reduced. In the Sheffield study, of those interviewed, 41 % were unhappy with the food the family ate, 32% were specifically worried about their children’s diet and 77% said the way they ate had changed due to a change in their circumstances. The difficulty in providing an adequate diet for a family when living on income support or unemployment benefit is well recognised and there is growing evidence of the problem of malnutrition in young children and the lack of iron in some children’s diet. Some early work on homelessness and health visiting in 1987 – the Bayswater Project – stressed the difficulties caused to families through a lack of or poor cooking facilities. This study showed that 95% of families interviewed had poor cooking facilities and consequent poor diets. More recent studies in Oxford and Reading have revealed similar results. A single mother with three children interviewed for an article in the Health Visitor Association Journal stated: ‘The cooking facilities are so appalling that we have to eat out. Nearly all the money goes on eating out. It is mainly fried food from the fish and chip shop chips and more chips the kids say. If it is fine we go on the beach and then I do sandwiches. ”

The physical growth and development of children can also be effected by their living conditions and poor diet.

Issues effecting social health

- Environment

- sharing of facilities

- overcrowding

- play space

- safety – accidents

- poor hygiene

- Education

- lack of nursery education

- poor school attendance

- no space for homework

- lack of continuity of education

- learning difficulties

- Access to services

- health

- social services

- DHSS

- voluntary agencies

- local authority – housing

- .Personal situation

- unemployment

- single parenthood

- relationship breakdown

- mobility

- income

- harassment

Social Health

The social health of children living in poor housing conditions can be affected by a variety of issues ranging from education, access to services, the effect of the actual environment to the personal situation of their main carer. A number of these are listed above.

The effects of poor housing and homelessness on children’s health and that of the adults that care for them cannot be queried. The issues highlighted in this paper illustrate some of these effects and all show the importance of a comprehensive assessment of need and of the provision of adequate services to meet those needs. There is no doubt that the circumstances of children’s lives has a great influence on their health as adults and that a great deal of ill-health in later life could be prevented by better initial health and social care and by work to alleviate the adverse conditions known to effect children’s health (HAVA, CPAG, Save the Children 1992).

It is doubtful, however, that the health and social services available today are allowing this. Purchasing and providing of services and the market economy now prevalent within the NHS and the wish by government to have all services based upon a General Practitioner’s registered patient list means that unregistered patients, often the homeless, are missing out. Recently published work from the four Thames regions showed that the NHS internal market is failing to meet the needs of the homeless and highlighted major gaps between policy statements and reality. It was clear that when services worked, this was due to the commitment of the staff involved.

The following quote from the 1986 Church of England report “Faith in the City” perhaps clearly reflects what a house means and what good housing can achieve: “A house is more than bricks and mortar, it is more than a roof over one’s head. Decent housing is a place that is dry and warm and in reasonable repair. It also means security, privacy, sufficient space, a place where people can grow, have choices, become more whole people.

References

- Blackburn C (1993) “Wealth and the nation’s health”, Health Visitor, Volume 66/7 July 1993

- Bosanquet N (1972) “Inequalities and health” in Townsend and Bosanquet” (Eds) Labour and Inequality, Fabian Society.

- Department of Health (1992) “Health of the Nation” HMSO, London.

- Field F (1973) “Unequal Britain”, Arrow Books Limited, London.

- HMSO (1990) “The Public Health 1990” Final Report, Chief Medical Officer, Sir Donald Acheson.

- Health Visitors’ Association/Child Poverty Action Group/Save the Children (1992) “Give us a chance”, HVA, London.

- Seymour J (1993) “Who likes to B&B beside the sea?”, Health Visitor, Volume 66/10, October 1993.

- Sheffield County and Priority Services/ Sheffield Health Promotion (1993) “The health needs of children living in temporary accommodation”, Sheffield.

- Townsend P and Davidson N (1982) “Inequalities in health”, the Black Report, Penguin, Oxford.

- Vickers M (1991) “Health and living conditions of homeless families in Oxford city”, unpublished literature review and analysis of collected data.

- Wedge H and Prosser P (1973) “Born to fail”, Arrow Books Limited, London. Whitehead M (1987) “The health divide”, inequalities in health in the 1980s, HEA, London.

Housing And Health In Scotland

Sir John Crofton Professor Emeritus Respiratory Diseases, University Of Edinburgh, Member Of Scottish Executive Of The Public Health Alliance

Introduction

For the last ten years or more I have been concerned with problems of multiple deprivation in Scotland. One of the most constant complaints from people in these areas is about their housing, especially about cold damp housing. In view of the decrease of available housing, the numerous complaints about housing quality, the relatively recent careful scientific studies about the effects of poor housing on health and the present complexities of housing provision, the Public Health Alliance in Scotland decided that it might be useful to produce a report which could be used by bodies and individuals concerned about this major health and social crisis. I have only time here to give a very short summary of some aspects of a fairly comprehensive report.

Poverty in Scotland

Scotland has a higher level of poverty than the UK as a whole. For instance 16% of the population was dependent on Income Support compared to 13% for the UK as a whole. In 1989 the average manual worker in the UK earned £335.56 a week. 80.4% of manual workers in Scotland earned less than this. The average weekly wage of Local Authority tenants was £115,86 and for Housing Association tenants £153.32. Since 1979 Local Authority rents have risen by 370%, which is more than twice the rate of inflation In 1992 1 in 3 households in Lothian and Strathclyde regions, the largest inhabited regions in Scotland, was said to suffer financial hardship. In Scotland 25% of children live in households receiving Income Support which is an increase of 108% since 1979. 38% of children live in households with less than 50% of the average income, often accepted as a definition of poverty.

Fuel poverty

Fuel poverty is also more severe in Scotland. It costs 55% more to heat a house in Glasgow compared to a similar house in the South of England, owing to the colder, wetter and windier climate in Scotland. It is suggested that no household should have to spend more than 10% of its income on fuel costs. The average for all Scottish households was 5.9% but for low income pensioners it was 13.5%, for single parents 12.7%, for the poorest 20% of the population it was 11.5 % and for other pensioners 10.5%. In 1990 somewhere between 300,000 and 600,000 households in Scotland had fuel debts or difficulties in paying their fuel bills. In 1991 55,000 households had their fuel bills paid direct to the DSS in order to avoid having gas or electricity cut off, but this, of course, had an important influence on their poverty. Of course the new increase of VAT will exacerbate all of this.

Housing defects in Scotland

A government survey in Scotland in 1991 showed that 4.6% of houses were “Below Tolerable Standard”, that is to say should not have been inhabited at all. Some 20.8% suffered from damp, serious condensation or mould. Shelter calculated that some 120,000 children were exposed to cold and damp in houses.

Health risks from cold and damp

Although the inhabitants of cold damp houses have for many years claimed that these had an ill effect on their health any good scientific evidence for this is relatively recent. Dr Sonja Hunt and her colleagues carried out the first really good “double blind” survey in a deprived area of Edinburgh with dampness measured by Environmental Health Officers and the questionnaires to the householders carried out by another group in ignorance of the dampness assessment. This survey showed excess of respiratory illnesses, diarrhoea and “aches and pains” in children. The survey was later repeated on a larger scale in Glasgow and London (Southwark) with the same results. There have been a number of similar surveys. Some of these surveys have shown a similar excess of illnesses, like those in children, in adults but this has not reached statistical significance in all surveys.

In 1989 there were 152 hypothermia deaths in Scotland but there is a much larger excess, 4,000-7,500, of winter deaths compared to summer in Scotland. These are mostly from chest or heart diseases. This winter excess is very much higher than in colder continental countries with better housing.

Mental Ill Health

It is much more difficult to dissociate the housing influence from the many other elements of the poverty complex which give rise to mental ill health. The main excess of mental ill health is in anxiety and depression. Obvious factors are the cold, damp and fuel poverty already mentioned. High rise flats with lift breakdown, vandalism, litter, crime and lack of play areas for children are obvious additional factors.

A survey by the Scottish Health Visitors Association of homeless families in temporary bed and breakfast accommodation has shown that, after moving in to such accommodation, there is a significant increase in children of diarrhoea, respiratory illnesses and accidents. In parents there is an increase of anxiety, depression, pregnancy complications and a 25% incidence of low birth weight, compared to a national average of 10%.

Homelessness

There has been a great increase in homelessness in Scotland. Applications by homeless people increased from 16,438 in 1983 to 39,500 in 1991/2, an increase of 140%. Of those accepted by local authorities as actually homeless the increase was from 7,487 in 1978/9 to 17,800 in 1991/2, an increase of 138%. Over the same period the Scottish local authorities, the only bodies with a statutory duty to house the homeless, have lost 25% of their housing stock, mainly through the “Right to Buy” policy. Therefore the demand has increased by 140% and the stock to meet that demand has decreased by 25%, a tragic paradox.

Homelessness among young people

Government policies suggest that young people should be looked after by their families and should not need outside help. Shelter in Scotland carried out a survey of young homeless people in 1990/1. They found that 32% had come directly from care, that 14% had been formerly in care and that 18% had no family support; these categories therefore comprise nearly two thirds. In addition 24% had some physical or mental disability, not usually very severe but enough of course to add to the misery and the difficulties. 12% were under supervision or probation.

These young people face very considerable difficulties. There are no longer DSS grants for 16 and 17 year olds. Private landlords require an initial deposit. Formerly this could be provided by the DSS but this is no longer allowed. There are great difficulties in providing furniture; in Scotland some voluntary organisations try to meet this need but there is no statutory provision. The Bridges Project in Edinburgh has looked at the problems among these young people and has found many of them suffer from quite considerable malnutrition owing to poverty and inexperience. Many have migrated to London hoping to find work there. They often run into all sorts of problems. Shelter, with Scottish Office financial support, now has a scheme to help such young people to return to Scotland and to try to rehabilitate them here.

Sleeping rough

In the last census in 1991 an attempt was made to enumerate the numbers sleeping rough. This was only carried out in known sites in the main cities. 142 were found. This is almost certainly a very considerable underestimate. Many young people are temporarily, but recurrently, roofless. In Edinburgh a psychiatric team in 1992 examined the health problems of people found to be sleeping rough. They found 65 (which suggests again that the census estimate for the whole country was a gross underestimate). To their surprise they only found 3% with actual psychosis but some 74% had alcohol dependency (which could of course be either the cause or the result of their problems). However many also had physical illnesses or depression. At the same time the same team carried out a survey in Edinburgh lodging houses. Here they found a much higher incidence of psychiatric illnesses. Some 22% were ex-psychiatric hospital patients, 36% had problems of alcohol or drug abuse and 28% had some form of cognitive impairment.’

It will be seen therefore that there were considerable health problems both in those who were sleeping rough and in those who were in hostels. .

Recommendations by the Public Health Alliance Scotland as a result of the Report’s survey:

1 There is a major national problem of poverty and marginalisation which can only be tackled fundamentally at national level through political action. Actions would involve upgrading allowances to decrease gross poverty, developing social mixes in the former marginalised areas and concentrating on economic efforts in those areas. In Scotland the government has made some moves in this direction in four of the worst areas but this is a very limited part of the whole problem.

2 Major efforts have to be made to rehabilitate the vast backlog of cold, damp houses. The Audit Commission has criticised heavily the inadequacy of this action in Scotland. Remedial action, they found in a survey in 1991, was not even keeping up with the deterioration. Vastly more resources have to be put into this. There should be further research into the most cost effective way of insulating houses so that they can be kept warm with minimal cost. In Easterhouse, a deprived area of Scotland, through the tenants’ action and a grant from the European Union, together with Local Authority funding, a group of houses have been upgraded, insulated and tapped into sun energy. This has resulted in decreasing fuel costs from an average of £30 a week to £5. The health of the families in these houses is now going to be monitored and compared with similar houses which have not been upgraded. Somewhat higher initial capital outlay can result in tremendous decrease in running costs.

3. Mental health Every effort ought to be made to improve the poverty complex. In the housing field the abolition of cold, damp housing and the improvement of housing management (with more local management, Tenants’ Associations etc) should greatly mitigate the problems. I am most impressed with the tremendous improvement of mental health, through greater self-confidence, both for individuals and the community, which results from community development projects, which should be greatly encouraged.

4 Homelessness: There needs to be a vast increase in “social housing” at affordable rents. This could partly be funded from reducing mortgage tax relief and using the money for social housing. The abolition of the “Right to Buy” should be seriously considered. Every effort should be made to abolish the use of bed and breakfast as homeless temporary accommodation and to replace it by temporary furnished accommodation which has been shown to be much more healthy, both physically and mentally. In order to improve the amount of housing there should be substantially greater Housing Association financing. Young homeless people should become a statutory responsibility of both the Social Services and Housing Departments. The problem of providing furnishings for impoverished people who are homeless, so as to get them started, must become a statutory responsibility and be appropriately financed.

Housing And Health, An Overview

Lorna Arblaster Research Fellow In The Department Of Public Health Medicine, University Of Leeds

Introduction

In the last year I have spoken to a number of Directors of Public Health in Yorkshire and elsewhere. Many are concerned about the effects of inadequate housing on health. However I feel that they lack a framework for addressing the problems effectively; the framework necessary for working at the different levels referred to by other speakers.

I want today to describe my framework for considering housing problems which I hope will clarify the issues and enable progress to be made.

First I want to look at some of the policy changes which have been introduced since 1979. Secondly, I want to look at the health of people in temporary accommodation, the health of homeless people on the streets and in hostels, and also at the health of people living in poor quality housing, to consider key issues which these different housing situations highlight.

And finally I want to return to look at policy issues and at what, in my opinion, needs to be done.

Policy changes

In 1979 the Conservatives regarded their housing policies, especially the “right to buy”, as key to their election success. In government they set out to expand owner occupation and reduce public expenditure on housing. They also set out to restrict the role of local authority housing departments to that of “enabler” rather than a “provider” of housing. In addition deregulation, such as the abolition in 1980 of the Parker Morris housing standards thus allowing each local authority to decide its own standards, and, deregulatory policies with respect to private landlords and the private rented sector in general, were effected. By 1990 one and a half million public sector dwellings had been sold. The sale of council houses was the largest of the government’s privatisation programmes. Receipts from sales for the ten years 1979 to 1989 were more than £17.5 billion. This represented 43% of all privatisation proceeds over that time. By the end of 1993 receipts had risen to £28 billion which was more than the total of the next three largest privatisations – gas, electricity and BT put together.

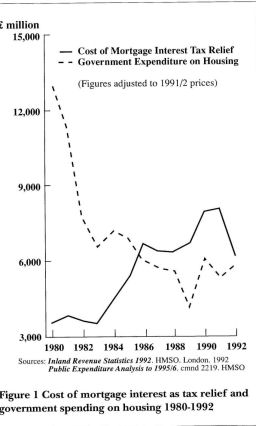

Government expenditure on housing fell from £13 billion in the year 1979 to £5.8 billion in 1991. Figure 1 shows the expenditure by government on housing since 1979. Over the same period government spending on social security, education, health and social services increased in real terms (see table).

Table 2: Government spending on various functions 1979/80 and 1991/92 (£ billions)

| Housing | Health | Education | Social Security | |

| 1979/80 | 13.1 | 25.6 | 24.4 | 46.6 |

| 1991/2 | 5.8 | 37.4 | 29.6 | 70.0 |

Following the 1993 Autumn Statement government expenditure on housing is set to be reduced by a further £1 billion this year (1993/4).

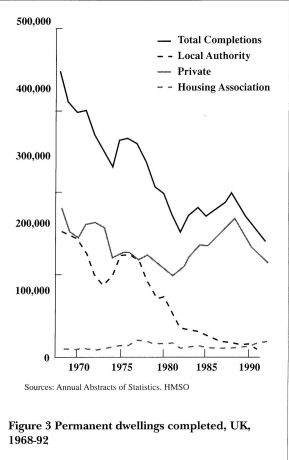

Figure 3 shows the number of permanent dwellings completed each year in the UK since 1968. The upper black line shows the total number of dwellings completed, the grey line shows private houses, the black broken line those built for local authorities and the bottom broken grey line, those built for housing associations.

Local authority and housing association houses together are often referred to as “social housing”, housing which has traditionally been subsidised by government for people who are less well off. The concept of a “subsidised sector” still lingers but is needs redefining. For instance, the annual subsidy provided per unit to the private sector through housing benefit is greatly in excess of that provided to local authority or housing association accommodation. Also mortgage income tax relief is a subsidy to the owner occupier.

In general the number of new houses completed in the UK has been declining over the last twenty years. This decline has occurred at a time when the number of households in the UK has increased by over 2 million, from 19.4 million in 1981 to 21.8 million in 1991.

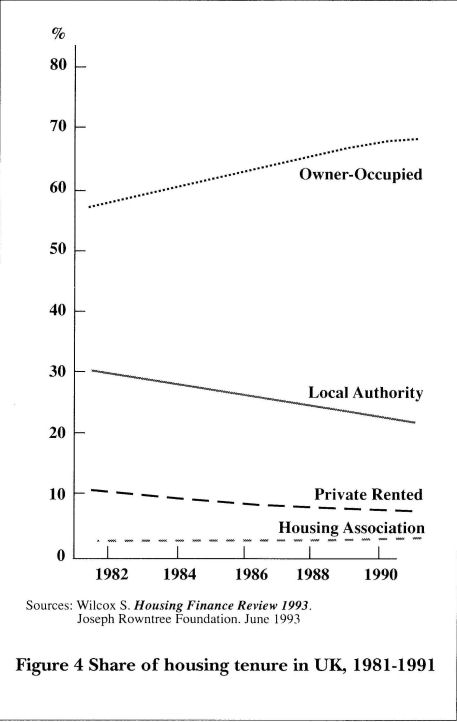

It is the government’s intention that housing associations rather than local authorities should be the main providers of social housing. Figure 4 shows the percentage share of housing tenure in the UK for 1981-1991 of different sectors. The contribution of the housing associations is important, particularly for people with specific housing needs. However, it can be seen from Figure 3 that the total number of houses built by housing associations has not matched the number formerly provided by local authorities. In 1993 housing associations completed 29,600 houses; during the same period 1,200 public sector houses and 114,800 private houses were completed.

The reduction in government expenditure on housing has resulted in less social housing being built. There have been several estimates of the number of social housing units that are required to alleviate social need. The National Housing Forum, the Institute of Housing and Audit Commission all consider that 80,000 social housing units are required each year over a period of ten years to meet this need.

Others such as the Housing Corporation and Shelter, the campaigning organisation, argue that if single people are to be considered as well, then 100,000 social houses are required each year over the next ten years.

The fall in government investment in social housing, the sales of council houses, and rent increases across all housing sectors, have combined to create a severe lack of affordable housing, particularly rented housing. This lack of affordable rented accommodation is key to understanding the present housing crisis. I want now to talk about the results of the shortage of affordable accommodation.

Homeless households

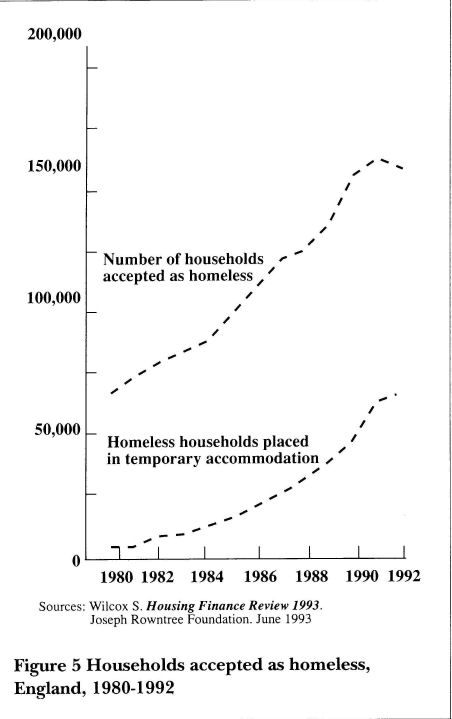

This shortage has resulted in an increase in the number of homeless households. Figure 5 shows the number of households accepted as homeless in England each year from 1980 to 1992. Homeless households in England increased from 62,920 in 1980 to 142,100 in 1992. (NB There was a revised system of recording after 1 April 1991.)

However if a household is homeless and in priority need then the duty towards them is different. Currently priority need refers to households where, for example, there is a dependent child, usually under 16 years of age, where the person or their partner is pregnant, where a person is vulnerable because of old age, mental illness or handicap, or where a person is physically disabled.

So if a household is homeless and in priority need and is not intentionally homeless and has a local connection, then and only then, will the local authority accept the family, or person, as homeless and be obliged to provide them with permanent accommodation. The households accepted by the local authority as homeless are often referred to as the official homeless”.

A government consultation paper Access to Local Authority and Housing Association Tenancies” proposes ‘fundamental changes to housing legislation particularly as it relates to homeless households. Such changes include: a redefinition of homelessness, so reducing” the number of homeless households; restriction of the local authorities’ duty to homeless households to emergency assistance for a limited period; and making more use of advisory services and accommodation agencies to place the homeless in the private rented sector.

Various factors have reduced the number of council houses available to house homeless households. These include the sale of council houses already referred to, the restrictions on expenditure by local authority housing departments, the disposal of local authority empty properties, and the voluntary transfer of stock to organisations such as housing associations, by the local authority.

The result is that many homeless households cannot be found a house immediately. They have to be placed in temporary accommodation. Examples of temporary accommodation are bed and breakfast hotels, hostels, short life accommodation, or, accommodation leased from the private sector.

Health of people living in temporary accommodation

Amongst this group, illness and disability has been found to be two and a half times greater than that of people living in permanent housing. The following table shows aspects of the health of people in temporary accommodation. Mental health problems are higher in this group. They include depression, relationship difficulties, isolation, suicide attempts, and heavy drinking.

- Physical illness and disability two and a half times greater than average

- More emotional problems amongst children

- More problems with pregnancy and childbirth

- More infections such as diarrhoea and vomiting

- Anxiety and depression affects half the adults

- Increased risk of accidents

Children often have emotional and behavioural problems such as delayed development, aggression, poor sleep or bed wetting. homeless women are more likely to have a small premature baby. In addition to health problems the process of becoming homeless is extremely socially disrupting. Often social support networks are lost. All of this is made worse by the uncertainty of not knowing how long the family will remain in temporary accommodation.

A study looked at children under five living in temporary accommodation who were admitted to hospital. It compared their circumstances with those of children admitted from permanent accommodation. The mothers of the homeless children suffered more adverse life events in the year prior to the child’s admission compared with the control group. The table shows life events in the previous year of mothers of children in temporary accommodation and those of children permanently housed. For example twice as many of the homeless mothers suffered a bereavement than those normally housed.

| Life events in previous year | Homeless | Controls |

| n=50 | n=50 | |

| Moved home | 49 | 13 |

| Immigrated to UK | 22 | 3 |

| Either partner changed jobs | 3 | 6 |

| Either partner lost job | 16 | 9 |

| Got married or divorced | 12 | 3 |

| Serious arguments | 17 | 7 |

| Assault on mother | 7 | 2 |

| Bereavement | 18 | 9 |

| Pregnancy | 28 | 27 |

| Involvement with court of law | 12 | 3 |

| Total median score (range) | 3 (2-7) | 1 (0-6) |

Homeless people living in temporary accommodation in the North West Thames Region used the health services more than other local residents. General practitioner consultations by the homeless were twice those of local residents. However, this use is less than their health profile might suggest they need. In view of their poor health even this extra level of consulting may not allow adequate consideration of their medical problems.

Visits to casualty departments were found to be four times more common amongst the homeless, than amongst other local residents.

Access to health care for homeless people in temporary accommodation may be a problem. Homeless people are more likely to live some distance from the GP’s surgery; 18 % lived 5 or more miles from the surgery compared with only 3% of local residents.

For many people in temporary accommodation it is very difficult to register with a GP. In this way people are denied access to the full range of primary care services. Access to mental health and social services is also likely to be difficult.

For example it has been found that only 53’% of children in temporary accommodation were fully immunised against diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough compared to over 90% of children in the general population.

Official homeless people in temporary accommodation are not only likely to have more health problems but they are also more likely to have difficulty in accessing health care.

I said earlier that the figures for the official homeless do not include single people or couples without dependent children. They may be homeless, but as such, they may not be eligible for local authority rehousing. They are sometimes referred to as the “unofficial homeless”.

The health of people living in direct access hostels or sleeping rough

These are a smaller number of people with different health problems. Some of the health problems of people living in direct access hostels or sleeping rough:

- 30-40% have severe mental illness such as schizophrenia

- 30-40% abuse alcohol

- 50% have physical illness, frequently have more than one condition (respiratory disease, bronchitis, pneumonia, TB, arthritis, gastro-intestinal diseases, epilepsy and diabetes)

- suicide has been found to be the biggest single cause of death (23%) amongst those who sleep rough

- death occurs prematurely with a high level of fatal assaults and accidents

A third of this group have severe psychiatric problems such as schizophrenia. A third of homeless rough sleepers and hostel dwellers abuse alcohol. Half of these homeless people have chronic physical illnesses, often having more than one disease. There is a consensus that there are more people in this group with psychiatric problems than there would have been 5 to 10 years ago.

Some people question whether this increase could have resulted from the discharge into the community of people from long stay institutions ie. people with learning difficulties or long standing mental health problems. However this may not be the case. A British Medical Journal editorial suggested that it is more likely to be due to changes in the policy of admitting psychiatric patients to hospital (there is an increasing reluctance to section patients thereby infringing their rights) together with the lack of low cost accommodation, which has caused more of the so called “revolving door” psychiatric patients to be present amongst the homeless.

It is interesting to note here that the number of psychiatric beds in England declined from 148,000 in 1954 to 45,000 in 1992.

Not only are there more psychiatric patients amongst the rough sleepers and hostel dwellers but there are more young people in this group. Changes in 1988 to the social security benefits for 16-17 year olds, together with high levels of unemployment, are thought to be the cause. In October 1990 at least 55,000 unemployed 16 and 17 year olds were without a job, a Youth Training Scheme place, or any benefit at all.

People who live in direct access hostels or sleep rough have severe health problems, particularly mental health problems, and there are increasing numbers of young people amongst this group.

The health of people living in poor quality housing

According to the Department of Environment the number of houses unfit for human habitation in 1991 in England and Wales, was over 1.4 million, that is 7.4% of houses.

There is a massive backlog of disrepair and deterioration of council housing stock because of the lack of investment.

However the properties in most serious disrepair are in the private rented sector. Twenty per cent of this housing is unfit, which suggests that one in five tenants do not live in decent conditions. Houses in multiple occupation (HMOs), home to 2.5 million people, are in the worst condition. Without adequate investment, either public or private, Britain’s housing stock is deteriorating.

III health results from living in badly designed, poorly built houses and flats which are damp, cold, poorly lit and with shared amenities. Home-related accidents are the commonest cause of death in children over one year of age.

Analysis of Home Accident Surveillance System data shows that almost half of all accidents to children were associated with architectural features in and around the home.

Damp and mould cause chest problems such as asthma and wheezing. The presence of damp also leads to depression. Mental distress is a feature of unsatisfactory housing. It is aggravated by other factors associated with poor housing such as fear of vandalism and crime, lack of security and social isolation.

These then are just some of the health problems of living in poor quality housing.

Other aspects of reduced government expenditure on housing

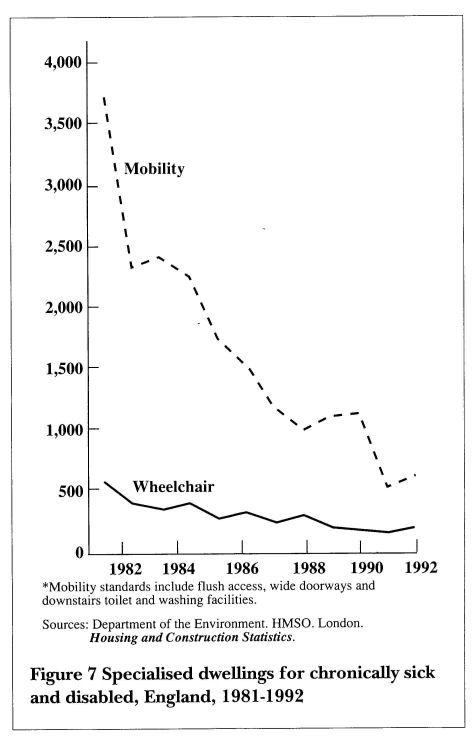

There are other health consequences of the reduced investment in housing besides homelessness or living in poor housing. Without investment there has been a reduction in the number of specialised dwellings built for the chronically sick and disabled in England since 1981, as shown in Figure 7.

Another consequence is the ill health and stress, including racial harassment, experienced by front line staff of local authority housing departments.

The need for increased public investment in social housing

In 1991 more than half of all new households could not afford to rent or buy a house or flat on the open market. However it is the present government’s intention to promote increased owner occupation for 85% or more of households. Figure 8 shows the percentage of owner occupation tenure in some other European countries.

Owner occupation in some other European countries

- England 68%

- Denmark 52%

- France 51%

- Austria 50%

- Netherlands 43%

- Sweden 39%

- Switzerland30%

According to JK Galbraith there is no country in the world in which low cost, affordable housing is produced by a market system economy. Such housing requires government subsidy. This view was supported by an article in the Financial Times which stated that institutional investors will not be prepared to invest up to 45% against the security of a tenanted home. This is the amount of money which housing associations will, from 1995 be expected by the govemment to raise on the open market towards the capital cost of new social housing.

Since 1979 there have been far reaching changes in the health service, in local authority housing departments and in social services. Those who work in these various departments are reeling from the insecurity of changes in function and from numerous changes in government policies. In my opinion there is a need for better understanding of each other’s changing roles.

However local authority housing departments have suffered particularly from a severe lack of resources and the undermining of many of their functions.

Expenditure on housing fell from £13 billion in 1979 to less than £6 billion (£5.8 billion) in 1991 whilst over the same period spending on social security, education, health and social services increase in real terms all shown in Figure 2. There is a need for all of us to be aware of the implications for social housing of the lack of government investment in housing. Shelter estimates that 100,000 social housing units a year for the next ten years are needed to alleviate social housing need. In 1992 they estimated that this would cost £6 billion a year.

In terms of national expenditure this is a small price to pay for houses to satisfy what is a basic human need, and to prevent the catalogue of ill health we have heard about today.

In addition to a national political response, there is a need for better collaboration between the health sector, housing authorities, social services and other relevant agencies such as housing associations. They should unite to call for more public investment in social housing.

This is the only way to stop, and to reverse, the health damaging effects of the housing policies of successive Conservative governments.

Stress Caused By Homelessness

Stephen Maybury

Unemployed Consultant Civil Engineer, Homeless And Vendor Of The Big Issue

The Big Issue is not some kind of charity. Selling The Big Issue is the same as selling the Evening Standard or the Times. Vendors purchase papers from The Big Issue, sell it to the public, and the difference between the purchase price and the selling price goes to the vendor. The difference between selling The Big Issue and selling the Standard is that to sell The Big Issue you have to have one prime and only qualification – you have to be homeless, As Stephen Maybury pointed out, “that is the greatest function of The Big Issue – to give an income to those that have absolutely nothing .. that makes one hell of a difference to the quality of one’s life – basic though it may be.”

The Big Issue also does many things for the people who sell it. There is the Vendor Support Fund which will help you, if you get accommodation buy furniture etc., or it may fund an educational course you want to go to. The Big Issue also has a housing unit which has an exceptionally high success rate in finding accommodation for homeless people.

The Big Issue sells in London, in Brighton, in Manchester, in Glasgow and there are plans to set up in Cardiff, which shows the problem is not something that is confined to London – it is nationwide – frighteningly so.

Stephen Maybury spoke about what happened to him over the last 2 1/2 years which resulted in his present position – homeless and unemployed, and as he pointed out “the experiences that I have been through have been experienced by many, many people. Not hundreds, not thousands, not tens of thousands but hundreds of thousands of people up and down this land have gone through, in one degree or other, what I have been through. It is not a pleasant experience”.

Speaking to the conference possessing basically what he was standing up in and very little else, Stephen Maybury gave details of his “extraordinary” history.

Three years ago he had a house worth in excess of £250,000, he was a consultant civil engineer, with a very successful and very happy career. But this time was not without stress. He worked in the Middle East for many years and for more than six years he had virtually no break whatsoever. At one point he worked, on average, 12-15 hours a day, 6 days a week, for five months, after which he had less than one week’s holiday back in England. After six years of that pattern of life he was mentally and physically drained. As he said, “that is stress. It is stress that led to be becoming homeless and stress of course came to a great degree afterwards”.

When the recession hit, it affected his field worldwide. His income dried up, and at the same time the mortgage rate soared. He was faced with payments averaging £2,500 a month, and no income. In about four months he was out on the street- as Stephen pointed out “they don’t give you very much time”. This was a very stressful time: “it is a terrible thing to be dispossessed of your home, especially one that you have loved and, in my case, worked very hard for”. He had the final notices to quit. The bailiffs came. “They were very kind. They obviously hated doing their job. I was just one of an endless list of people who they had to do this to”.

He got the coach down to London and spent the night on a bench near the Serpentine in Hyde Park – “I can’t remember in the whole of my life being so cold”.

Eventually he contacted Shelter who directed him to a hostel – “That was an eye-opener. Nothing in my former life could have prepared me for that .. It is the most dreadful experience, it’s debilitating, it destroys, because you are no longer a person. You are processed – forms are filled in about you, you are allocated a bed, there are cockroaches, there are drunks, there are people taking drugs. And nobody cares – Nobody gives a damn. The attitude is ‘They are in a hostel- they are housed’. Once you are in there you can regress, you can go down so fast and so far it is unbelievable, particularly if you are a young person. They have no hope, unless they are fished out of these places where – they can have their whole lives destroyed”.

Again it was a very stressful experience living like that.

Stephen finally got into a B&B, which was better, “but they put you in a B&B and they leave you there. Nobody does anything, or makes any effort to get you out of there, to put you back on the road to employment, to housing, nothing you just sit there. And then the problems start” .

Step hen found himself very poor, and after spending most of his life working long hours, he suddenly found himself with no occupation whatever. You feel excluded from society – not even allowed to vote – Stephen called it “economic apartheid”.

Stress comes in again, exacerbated by hunger, and it distorts everything you do. A basically honest person will find themselves stealing bread from restaurant doorsteps, and stealing fruit from stalls outside shops.

There is also the problem of getting a job. You have no clothes so if you see a vacancy you don’t have the clothes to go for it. It’s a trap which is very difficult to get out of once you’re there. Stephen also described how drink becomes a problem: “You spend months doing nothing and every week the giro comes and at £40 a week, that’s £6 a day – I can just manage on that, you think. You have all the good intentions and resolutions but they all go out the door as soon as you’ve got that cheque in your hand. Take for example razor, shaving foam, shampoo – that is a major expenditure to you. One thing leads to another and you get absolutely blotto. You wake up the next morning and you’ve got £25 in your pocket to last two weeks and the whole vicious cycle starts again, unremittingly, until the next giro comes, and the next set of resolutions – it’s very difficult to pull yourself out of that. Many, many people do not. You see them in cardboard city. They haven’t made it don’t be too harsh on them for that-you don’t understand what many of them have been through to reach where they have”.

Eventually Stephen says he felt he had got to fight back. The fight back can be just as difficult as sitting back and accepting your fate. You’re still faced with the pressures of how to get a job. In addition, as Stephen put it “The most insignificant thing, which the average person would shrug off, when you’re in this state sends you into depression”. Very, very difficult to get out of.

The alienation from society continues. But, as Stephen said, “if you’re selling something like The Big Issue, I think that one of the first things you come across is the essential kindness of people. You are absolutely amazed about how generous and how kind people are and how much they are concerned. But you always come across those who say ‘Get a job’ and such like, and when they are kind it’s because of where you are, and it hurts. And again it depresses and it all adds to the stress. You feel that everything is against you. It is a peculiar feeling. Every situation that arises is somehow going to be to your disadvantage. You have no means to manipulate your fate.”

Stephen concluded, “I’m not there yet but I’m getting there slowly. And then, you thing, will the government do anything? The government I think is concerned with the percentage who are successful, the percentage who pay taxes, the percentage who vote. But the homeless, the very, very poor, they are not important. I’m fighting back and I’m getting there slowly, but many of my friends are not, they will not, something will have to be done somehow, but there are no magic solutions.”

“This is not something that has mushroomed in the last few years. It is something that has been going on for a very long time. Nobody, no matter who they are, can stand up and say it will not be solved now. The problems are so deep seated. They will take many years to put them right. But a start must be made.”

Housing For Community Care

Christine Davies Housing Researcher And Consultant

I am pleased to be here on behalf of the Labour Housing Group (LHG) who like the Socialist Health Association (SHA) is affiliatedto the Labour Party and is trying to influence party policies, in our case for housing. Housing, of course, spreads across so many areas of policy and professional practice that even those of you who have no political persuasion will, I am sure, be wishing to influence the government’s housing policies.